Dr Craig Jeffrey's book Timepass: Youth, Class, and the Politics of Waiting in India examines the lives of middle class Indian youth.

In his book Timepass: Youth, Class, and the Politics of Waiting in India Dr Craig Jeffrey suggests that unemployed young men in India are 'sometimes a force for good'.

He also argues that even though education does give the youth some freedom, it also ends up drawing them more tightly into systems of inequality.

The title of Dr Jeffrey's book refers to the 'culture of boredom' where young educated unemployed youth, caught in a Beckettian crisis, simply wait for something to happen in their lives.

Dr Jeffrey who speaks fluent Hindi as well as Urdu is a fellow and tutor in Geography at St John's College, Cambridge.

In an email interview with Abhishek Mande, Dr Craig Jeffrey answered some questions:

What was the idea behind selecting the issue of unemployment amongst India's youth?

I was conducting research on education in India. It became obvious that there are very large numbers of highly educated youth in rural and small town north India who cannot obtain secured salaried work. These young people are crucially important economically, socially and politically. It would be no exaggeration to say that the activities of educated unemployed and underemployed youth in provincial India will greatly shape the future of the country over the next twenty years.

Why did you select northern India as the focus of your study?

My first research project focused on the Green Revolution and western Uttar Pradesh seemed an obvious base. Once I'd invested in learning Hindi and building social links in western UP I sort of got stuck there.

Click NEXT for more

Could you please elaborate on the areas you selected for your study and how much time you spent on this project?

I have done several projects in western UP. For my PhD I spent fourteen months in Meerut (1996-97). I then spent two years in Bijnor district (2000-2002), another six months in Meerut 2004-2005 and a series of shorter projects in 2007 and 2010.

Could you also please share with us some of your findings?

I've written a lot about education. Amartya Sen imagines education as an unproblematic social good.

In collaborative research with Professor Patricia Jeffery and Professor Roger Jeffery we argue instead that education is a contradictory resource: providing certain freedoms but also drawing people more tightly into systems of inequality.

I've also written a great deal about the experiences and actions of educated unemployed young people.

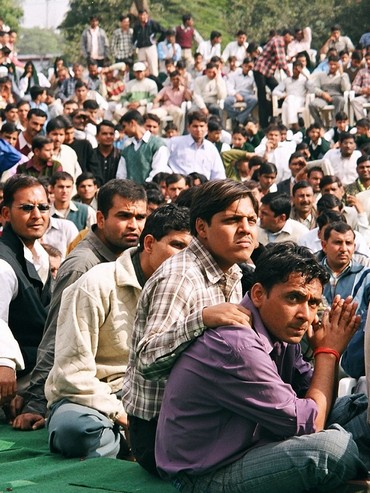

Many of the educated unemployed suffer from profound feelings of loss and boredom. They refer to themselves as engaged only in 'timepass' (passing the time).

Yet many of these young people develop vibrant youth cultures that bridge caste and religious divides. They are important politically, and they have even become involved in environmental projects in western UP.

Wall Street Journal says that Indians may be educated but they aren't employable. Is this more pronounced in tier two cities and small towns? If so, could you throw some light on why this might be the case?

On what basis do they make this claim? I think this argument is broadly correct for western UP, although one would need to point out that there are some people emerging from Roorki Engineering College, for example, who are highly skilled.

Partly because of the colonial inheritance, higher education in most provincial colleges are in a dire state, especially in social sciences.

Click NEXT for more

You had been to India in the '90s to study the Green Revolution. How would you say has India changed? Could you please tell us about the differences that struck you the most?

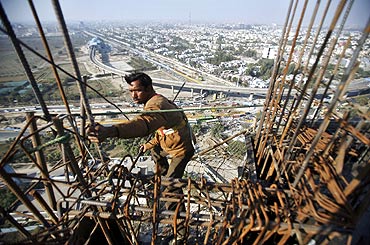

Well superficially things have changed a great deal: Delhi airport, the communications revolution, the capital's metro system. And in western UP (there is) a type of general 'Delhi-isation' of the urban fabric -- there is a multiplex cinema and traffic lights in Bijnor town now. But overall I'm struck by the durability of gender, class, caste and religious inequalities.

If you're at the bottom of the pile and living in rural western UP you will still be struggling to feed and clothe your children, and you will find it near impossible to find money for their secondary education and for their dowry.

Police malpractice, corruption, gender discrimination all remain major problems.

You mention that you came across 'educational corruption'. Could you please explain what you mean?

I'm simply stating what anyone reading newspaper in western UP already knows, that private educational entrepreneurs are establishing bogus institutions, you have to pay a bribe to enter many BEd and medical colleges, and there is also ordinary everyday corruption, small charges made by colleges for spurious reasons, delays in the processing of examination results, misallocation of scholarships, and many other misdemeanours. I go into the nitty-gritty in my book Timepass.

Click NEXT for more

You've suggested that unemployed young men are 'sometimes a force for good' because 'they have the time, energy and skills required to protest against injustice' and that 'they are building links between poor people and the state'.

Please could you explain how you came to this conclusion (were you witness to many instances of collective protests?) and also further explain this argument because unemployed young men are often considered a burden on the society?

Yes I witnessed collective protests, some of which were successful in uncovering corruption.

Many unemployed youth serve as intermediaries between the poor and state officials.

They are positive role models for younger children, even if they have not found secure salaried work. This is particularly the case among Muslims and Dalits.

You have suggested that education is not a sufficient basis for social mobility. What level of education are you talking about -- just a basic college / school degree? Do you believe that a person with an engineering degree from let's say an IIT will still face resistance if s/he tries to move up in the social hierarchy?

No, there is a very, very thin upper stratum of higher educational institutions -- like the IITs and JNUs of the world -- where students have excellent employment prospects. But these are islands of excellence in a vast sea of mediocrity.

Would it also be safe to say that the Dalit movement is stronger than the women's movement? Does this mean that it is more difficult for women to be more socially mobile than the Dalits?

Yes, probably, but difficult to comment at this very general level. It is probably hardest of all for Muslims in rural UP. And if you are Dalit or Muslim AND a woman, you are doubly disadvantaged.

Despite the rise of Mayawati, Dalits remain subject to numerous forms of everyday discrimination in UP (which isn't to say that nothing has changed).

Click NEXT for more

How strong and fruitful would you say are the bonds of 'timepass'?

Strong and fruitful in the short term. But when young people return to villages they often forget cross-caste and cross-religious friendships forged during college 'timepass' -- at least that's the case in western UP.

Timepass for young women in college is very different, I think, but this is not an area I've researched.

Would you say that the Indian middle class society is going through a typically Beckettian crisis where waiting becomes the primary concern of one's existence?

Not middle class society, but the lower middle class. Yes, waiting is a primary concern. And the absurdity of the situation, and people's use of humour, points to similarities with Beckett.

Click NEXT for more

How would you say an individual could get out of this ennui?

Migration is the obvious route, but it is difficult when you lack social contacts in major cities and brokers are keen to exploit youth seeking migration abroad.

How could we as a society do the same?

The extreme right and left have been most successful in mobilising youth in India. It would be good if people could reflect on how to breathe life into government schemes that already exist in the village level to enrol and energise young people.

What would you say are the aspirations of these young unemployed men? What is it that they want? What are their preoccupations? (At the risk of sounding like a suit, where do they see themselves five years from now?)

Some still hope for government work. Most now accept that their future is more likely to lie in the private informal economy.

Things are better now than they were in 2004-2005 when I did most of the research for the Timepass book.

Most of my friends in western UP understandably refuse to make predictions about five years hence: they leave these things productively open, waiting for opportunities without hard and fast plans.

You have suggested that these young men seriously want to become 'respectable citizens'. What is stopping them from becoming that? Is it just the lack of opportunity or the lack of desire that is a result of the lack of opportunity?

Interesting question -- a bit of both probably but mainly simply a lack of opportunity.

Another of your arguments has been that waiting can be 'a seed-bed for new cultural and political projects'. What will it take for it to reach this stage of fruition or do you think it already has? If so can you help us with some instances?

Things will change when young people in India are better equipped to learn about the problems and aspirations of those in other circumstances. They can develop what C. Wright Mills called a 'sociological imagination'. They see that their struggles are also the struggles of other "distant strangers".

As an academic from one of the finest universities in the world, what would you say have been your greatest learnings from this project?

Oxford is an ordinary university in many respects, with challenges that are not so wholly different from those experienced by some institutions in India. But that's a different story.