| « Back to article | Print this article |

At 29, she is India's first classical music entrepreneur

Meet Aishwarya Natarajan winner of the British Council's Young Creative Entrepreneur (YCE) Music Awards 2011 and who runs Indianuance, the first of its kind artiste management company for classical musicians.

Aishwarya Natarajan looked around a roomful of people and asked them if they'd heard of Shashank. A long silence followed. Some of them looked at each other and eventually the entire group -- most of them British -- said they hadn't even heard the name before.

Then Aishwarya asked them if they knew Pt Ravi Shankar. Immediately a few hands went up.

The 29-year-old was vindicated. She seized the opportunity and told her just why she was there.

"There are gazillions of Ravi Shankars waiting to burst on the scene. They are happy to play or sing for you; you are eager to hear them out and yet not one of you knows someone like Shashank. So there is some disconnect somewhere," she pointed out.

Aishwarya Natarajan runs Indianuance, an artiste management company exclusively for classical musicians and Shashank, a talented young flautist, is one of the artistes she manages

She won the British Council's Young Creative Entrepreneur (YCE) Music Awards 2011 on February 23 and as part of the award, got an opportunity to travel to London and Brighton to promote her idea and her company.

Aishwarya had two minutes to convey to the crowd sitting in the room what is it she exactly does and that was how she got it across to them.

'I quit and asked my parents to take care of me!'

In her previous nine-to-five avatar, Aishwarya Natarajan first worked in a Knowledge Process Outsourcing (KPO) firm and then for two well-known music labels -- Music Today and Sa Re Ga Ma.

"My first job was in a KPO firm in Gurgaon, which was through campus placement. Since we had to co-ordinate with people in the US, the timings were odd and work hours were long. I wasn't able to focus on my singing (she has been training in Carnatic classical music for over 22 years and also sings) and I realised I was spending lesser and lesser time on my music.

Besides I was doing something I had no clue about. As a 'business analyst', I was consulting and advising people on setting up IT businesses, about which I had no idea!

So I quit and asked my parents to take care of me till I find another job!

At the time I didn't know what I wanted to do except that it should be something related to music.

So after some research I figured I could apply to music labels. But then again I was not interested in those dealing with Bollywood music, something my mother deeply resented and reminded me her favourite phrase: 'Beggars cannot be choosers'.

After she gave me a three-month ultimatum I really got worried. I didn't want to get caught in another rut of a job.

I zeroed in on the music labels I wanted to work with, visited their offices and dropped my CV at the reception not knowing whether it would ever make it to the right person.

Finally I got a call from Music Today who offered me the job on the very same day of the interview.

This job taught me the most -- about contracts, licences, copyrights (etc).

It also gave me the freedom to explore and experiment. In the first six months I was sent off to Chennai to just speak with artistes and open channels of discussions.

Eventually I helped resurrecting Music Today's (almost-dormant) Carnatic music catalogue."

So after being neck-deep into music and the business for over half a decade, when she moved to Mumbai after getting married to Ramesh Ramanathan, an investment banker she was certain that she didn't want to join another music label.

And even as she almost landed a job in a different industry altogether, Aishwarya realised that she'd possibly never be happy being away from her first love -- music.

'A lot of classical musicians have just given off their recordings'

Aishwarya Natarajan was practically born in a music family. Her mother, Tara Natarajan used to be an All India Radio artiste and her father, RC Natarajan, a government servant has his roots in Bobbili, a village in Andhra Pradesh known for its Veenas.

The musical connection doesn't end here. Aishwarya's grandmother, now 89, continues to play the Veena and her brother Sukumar Natarajan plays the guitar, tabla, mandolin and the drums.

Sukumar, who works in the University of Bath in the UK, along with his wife Krishnaa Shyam Sundar help out Aishwarya in fixing venues, co-ordinating events and designing the website among a whole lot of other things.

The idea for Indianuance came about when Aishwarya was still in what she calls her 'music label' days.

She recollects, "At the time we worked with a variety of musicians. And every time we worked with classical musicians, I noticed that they were very simple, almost didn't know (how the business works).

Not a lot of them were dog headed about contracts and money and all of that. More often than not, it would be someone from their family or friends' circle that would represent them.

Traditionally, most of these artistes had to promote themselves at a time when music was not perceived as a great career option.

All these folks -- even the likes of Bhimsen Joshi -- have had tought times. And there have been times when record labels have not given them the best of the deals.

A lot of these singers signed off contracts given off recordings.

This stood in complete contrast with 20-somethings, straight out of college rock bands who would walk in with their manager who did all the talking for them.

He knew how things worked so he was the one who would go through the contracts, negotiate fees and talk about copyrights and the works.

(With the classical musicians) there is (an urgent) need to stay in control as much as possible of your music and your business because giving it away would mean that someone might not do justice to it or run away with it."

Which made Aishwarya think.

'Why don't these guys have managers?' she asked herself.

So when time came -- after she'd moved to Mumbai and had turned down a job offer -- Aishwarya Natarajan knew exactly what she should do.

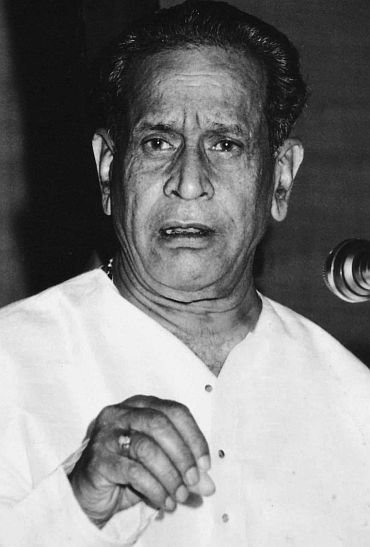

Image: A lot of classical Indian musicians like Pt Bhimsen Joshi have had to face difficult times when music wasn't such a lucrative career.

'Indians are a very suspecting people'

Convincing artistes to sign a manager to look into their work was however easier said than done.

In a country where the mindset has been 'why hire when you can get a family member to do it for free', Aishwarya's task has been uphill to say the least.

While we were still talking, Aishwarya received a Skype call from a well-known Carnatic violinist.

Aishwarya tells me that she'd been speaking with him for over a year but that they've started talking business only now.

I catch bits of the conversation, some of which is in Tamil, a language I don't speak or understand and figure that managing a classical musician in India can be very, very tough indeed.

"Shashank was the first artiste I signed up in (or around August) 2010. I had known him and had heard and loved his music. But I had never really worked with him. I approached him and he agreed. The idea was to just see how the model would work," she recollects.

Getting the artiste to agree is only a fourth of the battle won. Much larger issues lay ahead -- organisers in India and third party associates for instance, who look at people such as Aishwarya as something like swindlers.

"Very often, organisers call out names and tell us how they know the artiste and his/her family very well and that they don't see the need to talk to us.

Many of them see it below their dignity to talk to anyone but the artiste, which can get difficult for us.

The artistes on the other hand are put in a strange predicament because they often cannot take a hard stand. Sometimes they know their families for generations or owe their first concerts to them. So it gets very awkward.

I notice that this is prevalent only in India; I've never faced this in the West. There simply is no way out of it. At times we manage it; at others it is impossible.

The thing is we are a very suspecting people. In India there is a great amount of validation to say that we know XYZ so I don't need you.

It is an attitude problem and I suppose it will take some time before it changes."

Starting a management company for classical artistes is very difficult

Yet Aishwarya kept at it.

"In the initial months, I suppose we went about it (setting up the company) in a somewhat awkward way. I didn't know anything about setting up a business. Between the three of us (my brother, sister-in-law and me) I might have been the most business savvy.

We enjoyed the confidence of the few artistes who knew us. We knew it would be fine if we got a chance to experiment. And had it not been for the artistes who gave us the chance to try, we wouldn't even be here."

As months passed, the number of artistes started increasing.

"Starting an artiste management is fine but staring one for classical artistes is very difficult," she says.

Among those who signed up were the Gundecha Brothers, a duo of some repute in the Hindustani classical music circuit.

While all of this was happening, Aishwarya got a call from the British Council inviting her to participate in their awards programme.

"It hadn't even crossed my mind to apply," she says recollecting the long and tedious process of filling up the application form.

Finally on February 23, when her name was announced as the winner, it was as she says, 'one of those Sushmita Sen moments'.

"Things changed drastically after that. Indianuance wouldn't have gone into fifth gear (as it has now). The award itself has got us a lot (of name and reputation) but most of all it was a reinforcement that there were people outside of us who saw the potential in it. It was a confidence booster and made us look at things differently."

A two-week all-expense paid trip to England and a series of conferences, which the British Council had organised, as part of the Young Creative Entrepreneur (YCE) Music Award also helped her reach out to the right people in that part of the world and build contacts with those who matter within the industry there.

Back home, Aishwarya's music label background has also helped her negotiate better on behalf of the artiste.

"I have been (on the other side of the table) where I'd cut a deal on behalf of the label and was a hard negotiator. Now I know exactly what pitfalls to look out for while speaking with a label. (Moreover) it is lovely to say 'don't throw that at me I've been there'," she laughs.

However Aishwarya adds that even when she worked for the labels, she was 'always on the side of the artiste'.

"If there was an uncomfortable spot I spoke for the artiste internally," she says. "Besides I also kept a rapport with the artistes. If it is someone's birthday or anniversary, I'd make sure to drop in a line or make a telephone call. That's what's been helpful.

'Never do anything without a contract'

Today, about a year since they've set up shop, Indianuance has a little less than a dozen artistes and has managed to organise a two-month long, 25-city Europe and North America tour for Shashank.

They've also organised and curated a number of standalone concerts.

Some of them, Aishwarya tells me, include one with Aruna Sairam in Doha and another one that will conclude the Ahmedabad International Art Festival in October.

"The one thing we don't do is push our artistes down people's throats. We don't manage Aruna not any of the artistes that will perform at the Ahmedabad International Art Festival.

One of the things we do is work with such festivals and organisations and curate programmes for them that may or may not include our artistes."

Aishwarya's most recent achievement is the induction of one of Shashank's albums in the Society of Sound a joint project between (the high-end speaker company) Bowers and Wilkins and (the British singer-musician) Peter Gabriel's Real World studios.

"Shashank is the third artiste from the subcontinent after Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and U Srinivas," she says.

For a company that runs out of her home, was started with an investment of less than a lakh and works in a field as niche as classical music, one must admit is no modest achievement.

(She tells me her approximate value of business generated is over Rs 20 lakh)

Some of the things that have held Aishwarya in good stead are the low overheads -- she employs just one person in India while her brother and sister-in-law manage the show in England -- and the fact that she 'keeps things professional'.

"I never do anything without a contract and I never ever sign up artistes who I haven't heard," she says adding, "If there does happen to be someone whose music I haven't heard (like a classical pianist who's written to her), I make sure I independently hear his/her music."

The other thing she doesn't do is sign up young artistes. "That's usually because we are young ourselves and to promote young artistes will need a lot more groundwork than usual."

For now, the plan is to NOT sign up new artistes for the year but instead focus on getting work for those they already have.

"We'd also like to explore digital markets, make inroads into international festivals and someday perhaps (like Woodstock) make one of our festivals (like Saptak) popular in the West," she says.

"Besides, the (eventual) plan is to have at least one festival that we organise each year somewhat on the lines of (Shubha Mudgal's) Baajaa Gaajaa but one where professionals from (disparate) walks of life would speak about a particular issue in music. The idea is to intellectualise the process and have a nice festival."