| « Back to article | Print this article |

We are now on the verge of a 'b-school bubble burst'

Instead of stifling b-schools with autocratic punitive powers, an AICTE-like regulator should instead be aiding them with faculty development, upgradation and internationalisation, argues BIMTECH Noida Director Dr Harivansh Chaturvedi.

Two decades of economic liberalisation have proved that the dismantling the 'license-quota-permit raj' and infusing healthy competition into the Indian industry has been good for the health of the economy.

Despite upheavals in the global economy and, particularly, the worldwide recession of 2007-09, the Indian economy has continued to grow at a high rate without major turbulences.

Against the backdrop of profound changes in the industry and in the Indian economy, our social sector, which includes education and health, has not undergone any major transformations.

Our social indicators have always put India in the company of very poor countries of Asia and Africa.

Higher education in India has expanded rapidly during the last few decades, but our current Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) remains way below the global average.

In absolute terms, India can boast of having the second largest youth population in the world between the age group of 18 years to 24 years which attends college -- 14.6 million.

This is the second highest in the world, after China. But it is ironical that in the ranking of the world's best Universities and Colleges, India fares rather unsatisfactorily.

Please click NEXT to continue reading

AICTE has failed to ensure quality, access and equity in technical institutions

Higher education in India has been regulated by 13 regulatory bodies which including the University Grants Commission (UGC) and the All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE).

UGC came into existence in 1956 and AICTE in 1987 via acts of Parliament. AICTE regulates more than 11,000 technical institutions in the areas of engineering, management, pharmacy, architecture, hotel and catering management, applied arts, town planning and computer applications, etc.

AICTE regulations are very comprehensive but often not in-sync with changing times.

Most norms and standards prescribed by AICTE are static, input-oriented and related to physical facilities, faculty, etc.

The norms for approval of new institutions and programmes under AICTE's domain were framed in the 1990s when there were very few technical institutions, and mostly located in southern India and Maharashtra.

During the last few years, AICTE has received flak from all quarters for its inability to regulate technical institutions in a proper manner.

There is a plethora of complaints from students, parents, teachers, recruiters, media, parliamentarians and society in general, about the failure of AICTE to ensure quality, access and equity in technical institutions.

'All norms of infrastructure, faculty and curriculum have been flouted'

AICTE was envisioned to play the role of a catalyst regulatory body catering to the burgeoning manpower needs of the Indian economy in the post-liberalisation era.

Instead of fulfilling this role, it has become a medium for the nexus of corrupt politicians, bureaucrats and businessmen helping each other in making quick money through setting up more and more technical institutions (including management colleges).

All norms of infrastructure, faculty and curriculum have been flouted. Institutions have been allowed to be set up in difficult and remote locations, far away from the industry.

AICTE has given licenses to set up thousands of engineering colleges and management institutions without any relevance to the actual manpower needs of industry.

Business education under AICTE's control has grown mostly as a channel to make fast profits rather than as a serious attempt to groom managers suitable for the Indian and global economy.

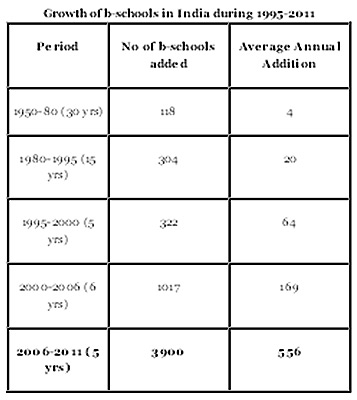

The exponential growth of b-schools happened during 1995-2011 and resulted in the increased supply of MBAs or PGDMs, far in excess of actual industry demand.

It is reported that 65 b-schools are facing closure

AICTE allowed a mindless expansion of b-schools during 2006-11, a period under which both the global and Indian economies witnessed severe recession and a slump in demand for MBAs.

It is owing to the faulty working of AICTE that we are now on the verge of a 'b-school bubble burst'. It has already begun and according to a Times of India report, 65 b-schools are facing closure.

It has also been reported that three lakh seats of engineering and management courses could not be filled up during 2011-12.

The National Knowledge Commission (NKC) has noted the failure of AICTE in its regulatory role and suggested disbanding of both AICTE and UGC.

The NKC Report (2007-09) states that "NKC advocates good governance rather than the prevalent system of prior control being exercised by AICTE in this sphere. The current regulatory regime focuses on punitive action rather than nurturing institutions'.

The role of AICTE has also been criticised by industry bodies for its failure to develop technical education in tune with changes in the industry, society and the global economy.

FICCI, in its report on the Regulatory Framework for Technical Education, has said 'AICTE has not been able to manage the multiple functions bestowed upon it as per its statutory mandate'. FICCI has recommended that AICTE be dissolved and a National Commission for Higher Education and Research (NCHER) be set up with an objective of minimum regulatory interference and flexible norms for the functioning of institutes.

'A good regulator of B-schools should be a professional agency'

Nobody knows the future of AICTE since the ministry of human resource development (MHRD) has been trying to merge it with the proposed NCHER.

Much will depend on the dynamics of the Indian parliament when the NCHER Bill is introduced by MHRD. However, we need an effective regulator for higher education which includes management education also.

In the ideal environment, a regulator will not be expected to behave like an autocrat enjoying unchecked punitive powers in hand.

A good regulator of b-schools should be a professional agency working with a positive mindset, equipped with trained professionals who are in touch the latest in management education and are also connected to Indian and global business via industry bodies and professional associations.

It should be managed by eminent management academicians and industry professionals. They should develop a vision and mission for Indian b-schools based on a comprehensive survey of global business education.

The regulator should establish relationships with Ivy League b-schools and international accreditation bodies like AACSB, EFMD and AMBA.

Illustration: Dominic Xavier

'For the next 10 years, the regulator should play the role of a gardener'

What should be the mandate for such a regulator?

Should it confine itself to development and nurturing or it should also wield punitive powers against those b-schools which do not fulfill their promises made to the regulator, students and recruiters?

Should the regulator provide a broad framework of business education and then leave it to the b-schools to work within that framework with scope for a lot of freedom, experimentation and innovation?

There are different models of b-schools regulations across the world. Should we emulate the models of developed nations where independent accreditation agencies ultimately decide what is right and what is wrong for management education?

For next 10 years, whosoever is the regulator of Indian b-schools, can play the role akin to a gardener who does everything starting from seeding, planting, watering and pruning -- allowing every plant, metaphorically speaking, to grow and every flower to blossom to their truest potential.

The AICTE, NCHER or any other agency designated for the regulation of B-schools can develop a new model of governance of institutions which is in sync with the current Indian and global realities.

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh

'India has all ingredients to become hub of higher education'

Since almost all b-schools face shortage of good faculty, the regulator can establish 20 Faculty Development Centers (FDCs) for undertaking a variety of activities in providing continuous education to faculty of b-schools.

These FDCs can be set up in twenty biggest clusters of management education, say Delhi, Pune, Mumbai, Hyderabad, Chennai, Bengaluru, Noida, Indore, Jaipur, Lucknow, Kolkata, Raipur, Bhubaneswar, Trivandrum, Guwahati, etc.

Each FDC can be attached to a reputed and well-established b-school whose faculty will offer training and PhD programmes to the faculty of b-schools in the neighbouring areas.

These FDCs can produce 200 PhDs and train 10,000 faculty members every year. Within the next 10 years, as many as 2,000 young faculty can be groomed to qualify for PhD degree by these FDCs.

To meet the challenges of globalisation, Indian b-schools have to adopt to the latest technology and become internationalised.

Both these imperatives are difficult, time-consuming and require huge fund supplies. Individually, many b-schools may not be able to invest hefty investment on high-cost technology and international accreditation.

But the ideal regulator can play a very constructive role in helping Indian B-schools to attract students from Asia, Africa and even from Europe and America.

The Ministry of External Affairs and the MHRD can join hands to use our embassies for promoting Indian b-schools in these markets. Of course, we will have to work hard in augmenting infrastructure of top 100 b-schools where foreign students can live and study comfortably.

India has all ingredients to become hub of higher education in management, engineering and medical sciences.

If Singapore, UAE and Malaysia can become hubs for higher education, India can also attract lakhs of international students in management and other disciplines.

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh