| « Back to article | Print this article |

Top designer, Amazon creative director, bottle-seller

Top designer, Amazon creative director, bottle-seller

Narendra Kumar was one the leading Mumbai-based designers protesting this attempt at segregation.

Just three days before his show in Mumbai, FDCI turned him down -- Kumar had demanded the right to show at both the New Delhi and Mumbai fashion weeks.

The designer, known for his maverick sense of style, decided to make his displeasure felt on the ramp.

"It took everyone by surprise," a journalist who was covering the beat at the time told me. "A lot of people didn't know how to react. There were those who felt he should have kept quiet and there were others who said 'Attaboy!' It was probably the first time that the ramp took on a political undertone."

Young upstarts from Mumbai taking on veteran fashion designers at the FDCI -- it was the perfect tabloid story and Mumbai Mirror, the largest circulating city paper in the metropolis, had been following it.

The next day, it ran a front page report titled 'Delhi, take that!' The headline ran along with a four-column wide photograph of the gagged models walking in a single file.

Another journalist who was at event told me there was much excitement at the venue after the show. This was way before Twitter and smartphones became ubiquitous, so the journalists who hadn't already rushed to the media centre to file their reports were making calls to their offices to update them about this unusual protest.

Curiously, Narendra Kumar himself didn't spell out the exact reasons. All he said in the post-show conference was, "It does not matter that I lost the case. I am just trying to make a statement."

In the years to follow, the restrictions were relaxed and designers were allowed to show at both fashion weeks. Kumar himself showed his Spring-Summer 2010 collection at Delhi, again to pin drop silence.

Narendra Kumar had been around long before 'the ramp fell silent' -- some even credit the inception of fashion weeks in India to him -- but it was this show that put him firmly in the spotlight.

In some ways, the show marked the beginning of 'fashion activism' for Kumar, who seemed to have discovered the power of the runway.

Since then, he has tried to reflect socially relevant issues. Some years ago, he paid tribute to an Allahabad lesbian couple arrested under the IPC section 377.

At the recently-concluded summer-resort season of the Lakme Fashion Week, Kumar attempted to recreate the 2006 sensation. The show, called 'Thought Police', saw about 40 bouncers dressed in khaki stand around the ramp, as models walked up and down the runway in his outfits.

Revolutionary as the concept was, many who were part of the audience as well as the photographers in the pit -- the primary dispensers of information from the shows -- were far from happy.

The presence of the Nazi-like 'soldiers' around the perimeter of the ramp meant that very few got a glimpse of the clothes.

So when Narendra Kumar says he is 'disappointed' with the 'overall' reaction to the show, I raise my eyebrows.

He tells me that the buyers liked the clothes as did a fair amount of people, but everyone according to him seemed to have missed the larger picture.

It is when he draws comparison to the 2006 show that I get the feeling he may have been expecting a wider and stronger reaction from the media.

Certainly, the show was relevant to the times but there was no front page coverage and certainly nothing that stirred emotions the way 'In Protest' did back then.

Then again, that has been a common complaint -- most of Narendra Kumar's shows invariably end up doing disservice to his clothes.

Top designer, Amazon creative director, bottle-seller

In the course writing this article, I spoke to several people about Kumar and his work. Practically all of them talked about his shows. It was only when I would pointedly ask them about his clothes, that they would tell me why they loved his designs (and almost everyone did).

A fashion writer who doesn't want to be named however told me she never thought of Kumar as a genius. She admits his clothes are great but there is, according to her, nothing that makes them stand out.

Nitasha Gaurav, stylist and former fashion editor at Femina, disagrees, pointing out that there is invariably an element in his designs that reveals its creator. "It could be a button here or a band there. But there is always something that will tell you it is a Narendra Kumar outfit."

Even though she agrees with the argument that his shows tend to overshadow his clothes, she adds after some thought, "Concept to Nari is everything. After watching one of his shows which used a lot of lasers, I was quite put off. Later, I figured he was trying to create that funky, youthful ambience. It made sense to me then. Also, when you think about it, you can always go to his stall (at the fashion week venue that is open to all) if you really are interested in seeing the clothes."

As for Kumar, he likes to see his shows as "a 15-minute film where I play everything".

He tells me that nothing drives him more than a good idea or a concept. "That idea is the seed for my collections and my shows; every show for me is like a film or a performance," he says.

(Much later, unsurprisingly, he would tell me one of his favourite movies is A Single Man, designer Tom Ford's brilliantly visual directorial debut.)

Kumar says his collections grow organically. "Once I figure out what major silhouettes I will work on, every piece usually works itself out. But I always need an idea, something that pushes me in some direction."

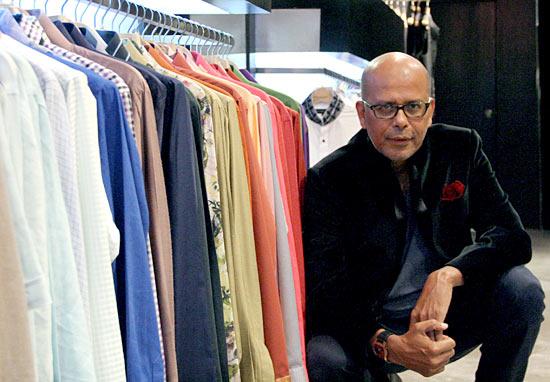

For a single show he creates around 40 outfits but, through the years, there are several more that must be customised for clients who he attends to at his store in the quiet, leafy Mumbai suburb, Khar.

The store is the only one from where he retails and meets his clients on appointment.

"A lot of the market is about customisation these days," he says. "So you end up doing about three to four designs every day. Your collections are where you can be creative. Else, it's usually what the customer wants."

***

When I visit him at his store, a soon-to-be married couple and their bridesmaid are already waiting. Kumar isn't to be seen.

The three young people make themselves comfortable and immediately start looking around. After some time, they decide upon a 'drape sherwani', one that seems not just incredibly heavy but also terribly hot for a beach wedding they seem to be planning.

Kumar arrives, breaks right into the group and starts giving his inputs on the outfit.

The young man, presumably in his twenties, confesses he doesn't want it to look too unconventional because "we come from a fairly traditional Marwari family".

He shows him a conventional sherwani at which the groom twitches his nose. He then goes on to convince the trio that the 'drape sherwani' would also go down well with his conservative family.

"You cannot push your customers into buying what you want," he tells me later. "You must know where to stop."

This is how, he says, it usually works -- after the customer walks in, Kumar lets her/him take a round of the store as he tries to gauge what their likes and dislikes may be. Once he's figured that out, it's cakewalk.

He believes men are getting more confident and are willing to try something new.

However when I ask if Indian men have stopped being lousy everyday dressers, his answer is an emphatic no!

Much of this 'confidence' is restricted to the wedding market, he elaborates.

It also explains why Kumar finally designed a wedding line that he debuted last year.

Top designer, Amazon creative director, bottle-seller

For Kumar who has trained under master couturier Tarun Tahiliani, it was turning a full circle.

"The wedding market is huge in India and it takes pure gumption to survive in the business without having a bridal line," Nitasha Gaurav says.

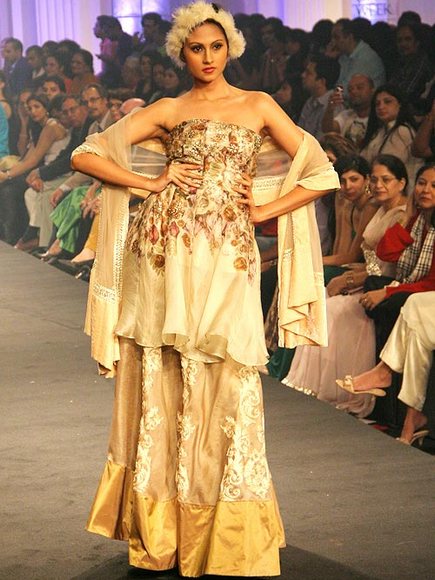

Recounting an oft-repeated story, Kumar tells me the inspiration for the bridal collection came to him at 6 am at a friend's place when she played a piece by Rachmaninoff on the piano (Rachmaninoff, one of the finest pianists of his day, was also an accomplished composer and conductor).

"There was something beautiful and intense about it," he says. "And that was really the seed of my line."

"I eventually went on to research about Rachmaninoff, his life, his music, the music of his contemporaries and the (famed Russian) Kirov Ballet."

The line itself was unconventional; it was minimalist and the brides wore no jewellery.

"It echoed the woman I believe is the modern woman -- strong and, at the same time, fragile, much like the ballet dancer who is so physically strong that she can stand on her toes but looks so fragile on the stage."

***

Over the years, Kumar seems like he is limiting his operations. He's closed down his store in Delhi and now stocks in just one store in Pune, besides his Mumbai store.

He tells me he doesn't sell anywhere overseas and only sells stock to people willing to purchase it outright (Most Indian designers work on consignment, which eventually translates into loads of unsold stock returning to them at the end of the season).

Even though his suits sell for Rs 40,000 and above, shirts for Rs 6,000 and above and a sherwani up to Rs 200,000, he is -- by at least two accounts -- a terrible businessman.

Kumar's manager Dharmesh Nathwani tells me his boss happily gives away his clothes to his friends for free.

In his defence, Kumar says he doesn't mind giving something to someone who appreciates it.

It doesn't make his partner, Kadambari Lakhani, very happy. "He isn't as commercial as I would like him to be."

I suspect though most of his business comes from his various tie-ups.

He's designed for Killer Jeans, has collaborated with the toy company Mattel and designed uniforms for Vodafone and the Vivanta group. When the Marriot Group of Hotels first started in India, he had designed their uniforms too.

He is the brand ambassador for Swiss Airways (which he flies whenever he travels overseas) and has created calendars for them as well for Japanese Tourism.

About a month ago, he took up a lucrative offer at Amazon as their creative director, he is helping them build their fashion segment in India.

It involves him working out of their office in Bengaluru, where he stays four days a week.

"One of the reasons I took up this job is because it will give me the scope to influence the thinking of millions of people. It's what I have always wanted to do," he explains. "The challenge is to subtly introduce fashion to Indians."

***

Interestingly, this isn't Kumar's first attempt at reaching out to the masses. Some years ago, he had, in association with designer Wendell Rodricks, introduced a pret line for Westside, the garment store run by the Tata Group.

Kumar is aware of the challenges before him; he was looking at a big one at the Amazon office itself, a place teeming with techies who rarely ever go beyond their pair of jeans.

Till the day when he walked in.

An Amazon employee recalls everyone talking about the "guy in the pair of green trousers." Few people knew who he was and what he did for a living, but it didn't take long for Kumar's trousers became a talking point in the office.

"Every day we would wonder what trouser he would wear," says the Amazon employee. "The day he wore a pair of dark blue ones, we went, 'Hmm. Those aren't colourful'."

Later, Kumar told me that when he walked into the offices of one of the bosses, "he told me he'd heard about my trousers before me"!

Top designer, Amazon creative director, bottle-seller

For this article, Narendra Kumar and I spoke on the phone and met several times over three weeks. The last of our meetings was over a long Sunday lunch where he took my questions over beer.

"Beer's not really my poison," he clarifies. "I enjoy my beer as much as my scotch and sangrias. It really depends on the place I am at and the people I am with."

Much like his diverse choice in alcohol, Kumar is vastly different with different people. It's quite amazing to see how quickly he switches his roles.

He is warm to his juniors, businesslike with his clients, pally with journalists and relaxed around his friends.

His voice often goes soft when he speaks of Kadambari, his partner for over a decade, to whom he credits his success. According to various sources, they are no longer together though both speak kindly and acknowledge the contribution each has made to the other's life.

To his family though, Narendra Kumar is as much an enigma as he is to most of us.

After much persuasion, Nandkishore Raman, Kumar's younger brother, agreed to speak to me about their childhood, beginning with why they share different last names.

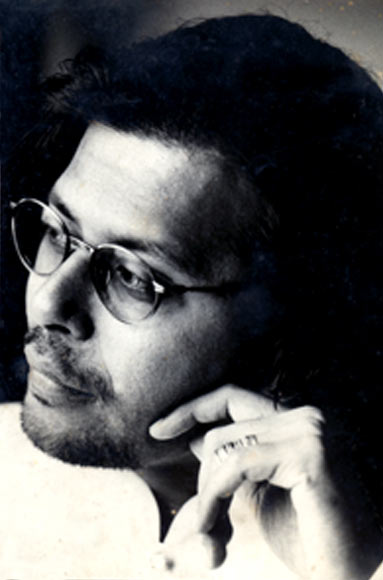

Fashion journalists of a certain vintage will probably remember a show featuring a letter from Kumar's father to his mother, professing his love and begging her not to marry the man her family had chosen for her.

The show, by far his most personal, told the story of their relationship -- of how a young Rukunuddin Ahmed rushed to the railway station, slipped the letter into a book and how a young Laxmi followed him without second thought.

"We found the letter many years later -- the paper had turned beige, the paper clip on it had rusted and the ink had turned green. I was moved and knew right then that my next show would be about their love and their courage," Kumar had told me earlier.

The two ran away from Hyderabad and moved to Mumbai, where Kumar's father retired as director of treasury for the government of Maharashtra.

The couple had an understanding -- the older child was to take the father's name and follow his religion; the younger one would take the mother's name and follow hers.

Thus, Narendra Kumar Ahmed and Nandkishore Raman.

The two brothers, separated by about three years, are as different as their names. Kumar is tall, slim, fit and wears designer labels. Raman is a tad portly and wears Arrow shirts.

Kumar wears his watch on his right hand, Raman on his left.

One talks about existentialism and social causes; the other lives a classic middleclass life, draws a decent salary and worries about the future.

Raman works as an executive assistant to construction magnate Niranjan Hiranandani. When he met me at his office, I kept looking for something that would identify the two as brothers... a mannerism, a physical feature...

But there is nothing in common between the two brothers who, in so many ways, represent the diverse worlds they lived in.

It wasn't surprising to learn they weren't particularly close to each other. Kumar had given me a hint during our first interview but didn't elaborate. Raman didn't get into too many details either, but confessed they weren't close as children to begin with.

Among the 'fond' growing up memories, Raman recounted his brother helping him with his drawing and painting.

"He was good at that from the beginning," Raman said. "But he was better at cricket! Did you know he represented our school in the Harris Shield matches?"

There may not be a lot of love lost between the two brothers but it is evident Raman admires Kumar to the point of hero worship. He may not know what the Esquire Big Black Book of Style is, but he knows it is a fairly important achievement in his brother's life. When he speaks of Kumar's accomplishments, he does so with a great sense of pride.

He admits that what pushed them further apart was Kumar's decision to go to fashion school.

"That was a different world. I didn't approve of it. Neither did my parents, especially my father. Though I think he would have been incredibly proud of him today had he been alive."

Top designer, Amazon creative director, bottle-seller

Rukunuddin Ahmed has been the single most dominant influence on the lives of the two brothers. Diverse as their personalities are, both remember him fondly and as an immaculately dressed man who carried himself with dignity.

Kumar recollects his buttoned up suits, Raman the Pakistani shirts he bought regularly from a local vendor in South Mumbai.

"He liked to be well-dressed. He always wore a tie and almost always a jacket when he went to work," Raman tells me.

But he was heartbroken when the older son decided to become a fashion designer. Like most of the young Kumar's friends, his first question was: 'Darzi banega (will you become a tailor?)'

***

Neither brother was particularly bright in school. Their scores were just about enough to get them to the next grade and so on. After graduating, Raman went on to study liberal arts at Wilson College and Kumar studied science at Elphinstone.

It was while he was sitting in the quadrangle of his college reading about Pierre Cardin's fashion show at the Taj Mahal Hotel (not very far from where they were at that moment) in the newspaper that he told his friend Pulin Bose he wanted to be a designer.

Bose laughed.

After graduation, Kumar worked for a while selling photocopying machines for Modi Xerox. He would also go from office to office in Mumbai's famed business district, Nariman Point, getting orders to photocopy architectural plans and other bulk documents.

Soon, he switched jobs to work for the glass division of Ballarpur Industries, which sold milk bottles to government departments.

"It wasn't like I wasn't doing well for myself. But I was just going from one day to another," he says.

Then he saw an advertisement in the papers about the newly formed National Institute for Fashion Technology in New Delhi. Getting admission required a year's experience in the business, so he quit his job and started working for a small garment manufacturing firm matching dupattas with kurtas, sealing them and packing them off.

Six months later, he joined another company called Jazz Man that exported shirts to European countries. Whenever he had time, he would design clothes and get them stitched by a local darzi (tailor) who'd been in the business for over 15 years.

One day, he tried to get the tailor to cut an off-shoulder dress; the man simply couldn't do it.

"That was the day I realised if I didn't know how to cut my own clothes, there was no way I could be anything in the industry."

As soon as the year was over, he applied to NIFT and received an interview card. He went with armed with three sketches and a garment he'd made -- a multi-layered, frilly yellow halter-neck dress.

At the interview, Kumar says he was the oldest applicant. He refuses to let me reveal his age but says his honesty may have clinched the deal.

"I told them I had quit my job and did not intend to go back. And I told them I would most likely get into fashion whether they admitted me or not!" "A month later, he got word that he had been accepted!

Top designer, Amazon creative director, bottle-seller

The two years at NIFT would change Kumar's life in ways he had never imagined. His teachers opened his mind and introduced him to new ideas. By the time he stepped out of the campus, he was friends with the great Rohit Khosla, J J Valaya (who was his roommate), Ashish Soni, Rajesh Pratap Singh and Manish Arora.

Kumar returned to Mumbai to work for Tarun Tahiliani where he earned his first pay cheque as a fashion designer, a princely sum of Rs 1,000. He worked with Tahiliani for three years before branching out on his own.

Then followed a phase when he flirted with journalism as the first fashion director at Elle India.

It was during this time, almost a decade and a half ago, that he met his longtime partner Kadambari Lakhani, an investment banker who had travelled to India on a holiday and stayed back for good.

Kumar credits much of his entrepreneurial ventures to her persistence and solid support. Lakhani says he gives her more credit than she deserves.

"He always had it in him," she says. "He had the ideas. All he needed was a push. He needed encouragement to handle the backend so he could concentrate on the creative side of the business. That was all I did."

The partnership has worked out well.

Earlier this year, Esquire listed Narendra Kumar among the 56 best menswear stores in the world. The list includes iconic brands such as Burberry, Tom Ford, Hermes, Prada, Louis Vuitton and Valentino among many others.

"You know, you begin with the belief that you will make it big one day," says Kumar, "be one of the best in the business. The truth is, however hard you believe, you never really think it will happen."

And then, one day, it does.

"I think my father would have been proud of this one. He would have really understood what it means." he says, tapping the thick book on the desk.

It is the first 'human' Narendra Kumar moment I've witnessed. There is a hint of something resembling longing and, perhaps, regret. After a moment of silence he declares a tad dramatically:

"Now I can die!"

***

Narendra Kumar likes to see himself as something of a vagabond who is isn't bothered about leaving a legacy. I suspect, though, that he sees a little bit of himself in his 18-year-old nephew who, unlike his parents, doesn't want a 9 to 5 job.

"He wants to be a filmmaker," Raman tells me. "I think Naresh is his favourite uncle."

Naresh?

"Yes, yes, I know you people call him (makes a funny face) Narry but he's always been Naresh to me and my wife."

In all the time I spent with Kumar, and the few hours I got with his brother, I could not figure out the dynamics between the two.

Raman tells me Kumar never acknowledges him or his mother around his fashion friends and that he prohibits Raman and his wife from wearing his outfits. "He tells us we aren't 'cut out' for it."

At some level, Raman seems to believe he could have done better if his parents had been a little more supportive. He tells me that when time came to choose, his mother chose to send Kumar to fashion school over his wish to learn hotel management abroad.

In the same breath, however, he admits "Naresh is a self-made man.

"To this day, he keeps track of my mother's health. We don't talk much, but we make sure we catch up every once in a while."

At the end of our conversation, I ask him if he loves his brother.

A long pause.

That shouldn't be a difficult question to answer, I tell him.

Raman looks away from me as if to compose his thoughts before replying:

"The problem is he is never open with us (family). He and I may not be very close, but I care for him now. Sometimes, I worry about him. He has nobody. He's got that huge house and he is all alone. Now, he's gone ahead and taken up a job in Bengaluru. What if something happens to him? Who does he turn to?"

***

My last meeting with Kumar is at his home, a huge but tastefully done apartment in a posh new residential complex in central Mumbai. We watch the sun go down as the city readies itself for a new week.

Tomorrow is Monday, which means Kumar will be on an inordinately early morning flight to Bengaluru to report in to work at Amazon. He won't be back until Friday.

The irony of not being able to live in this breathtaking house he's purchased with his hard-earned money isn't lost on him.

That is how life is, he says.

After talking about this and that, I finally excuse myself. Kumar sees me downstairs to the main gate through a swanky lobby with walls of glass.

We've been talking for about three weeks now. Our conversations usually ended with my requesting him to be available for a round of follow-up questions. He's been mildly amused but never irritated at this seemingly never ending interview.

As we wait for a taxi, he asks, "Why would you want to spend so much time interviewing me?"

I shrug in response. He smiles back, pats me on my shoulder and wishes me luck.

As my cab turns a corner, I look around to see if he's still there. I catch a fleeting glimpse of Narendra Kumar as he walks through the door and disappears into the glass lobby.