| « Back to article | Print this article |

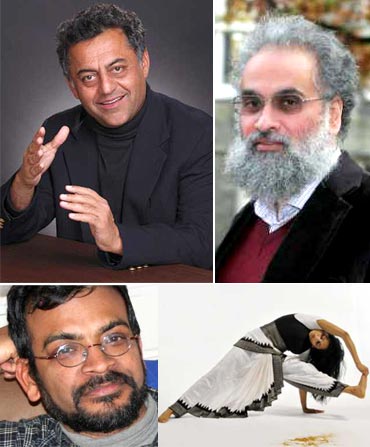

Meet the four Indian American Guggenheim Fellows

This year's Guggenheim Fellows of Indian origin are driven by the passion to stretch the limits, finds Arthur J Pais.

She is no swan. She is a fighter

Ananya Chatterjea will happily tell you she is a dance freak. She might also add, like she told a radio station recently, 'I think dance can do it all!'

"As a feminist, as a social activist, as a liberal, and as someone who grew up in Kolkata and admires (playwright) Badal Sarkar, I have known what dance can do to the conversation on social activism," Chatterjea, dancer, choreographer, founder of a dance theatre, and dance professor, told India Abroad.

Chatterjea, a tenured professor at the University of Minnesota, added: "We can read a lot of stories of how mercury is dumped into the oceans and how it affects people's health; but we can use dance to reveal the human condition vividly."

She has been singled out by Ms Magazine as one of the 'choreographers who are pushing the boundaries of what it means to be a woman and a dancer.'

Chatterjea, who runs Ananya Dance Theatre in Minneapolis, was recently awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship for choreography for blending dance and social justice.

Chatterjea is working on Tushaanal: Fires of Dry Grass, the second piece in a four-year antiviolence project exploring the experiences of women of colour. Her theatre has a dozen women dancers of colour with roots in India, Mexico and other countries. Among her more notable works is Daak or Call to Action, about people who are being replaced and driven away from their land to make room for heavy industries in West Bengal.

Chatterjea came to the United States with a scholarship to Columbia University to study global dance innovations and earned a master's degree in 1990. She began work at the University of Minnesota in 1998, after earning her doctorate from Temple University.

She says that her work began in India as a classical dancer more than three decades ago, having learned the craft from Sanjukta Panigrahi. Chatterjea soon became disillusioned with what she called "the commercialisation that had become attendant upon Indian classical dance forms."

She began to feel she wanted new ways to imagine her body. She also came to realise that in contemporary dance she would be "able to gain more perspective, actually, a deeper understanding of my cultural roots."

As a young dancer, she had participated in street theatre in Kolkata, where she critiqued, through performance, violence against women.

'I was also disturbed,' she wrote in her fellowship statement, 'by the "market" mentality that increasingly came to dominate the ways in which classical dance was being learned and performed on the concert stage. Through these questions, I arrived at the beginning of my journey as choreographer. I also learned that my inspiration lay, not in dancing about divinities, or mythological characters, but about everyday people and their daily struggles.'

In one of her earliest successes, Unheard Testimonies (1998), she was able to portray the story of a working-class woman gang-raped by policemen in Hyderabad.

Dance critic Marianne Comb has noted that some people who have a traditionalist approach may find Chatterjea's work surprising.

Some others are surprised that Chatterjea has been able to build an innovative dance theatre in the Midwest, and often explore Indian dance themes.

"There is quite a big liberal community in the Midwest and I found it natural to build a theatre here," she said. Her work has been supported by the National Endowment for the Arts, the Asian Arts Initiative, the Minnesota State Arts Board, and the McKnight, Jerome, and Bush foundations.

She has been taking her work to countries in Asia including Indonesia and Japan, the United Kingdom and Germany, and cities across America for more than 15 years. Her Unable to Remember Roop Kanwar, which premiered at the Museum of Natural History Auditorium in New York 14 years ago, received much critical acclaim. It was about Kanwar, who was burned to death on her husband's funeral pyre in Rajasthan.

Chatterjea's current production is part of a quartet dealing with how women experience and resist violence.

"We are dealing with the exploitation of land, gold, oil and water, and how this affects the lives of women," she explained. "I have women in our theatre who tell us about the devastation caused by gold mining in a number of countries including Congo and Malaysia and how it has affected the farmers, and the women, who as mothers, daughters and sisters, have to bear the burden."

The women associated with the ADT, she said, are not mere dancers. They participate in antiviolence, antiracist, antisexist and antihomophobic workshops, and they also work in health and nutrition for women, she said.

"She's not just teaching us to dance," said Preston Stockert, who has been with Chatterjea's dance school for about a year. "She's actually teaching us to care about something else. Not just further ourselves, but to further our artistry so we can make an impact on someone else or something else."

Ear to the ground, learning from the earth

In a migrant camp for raikas (shepherds) in Rajasthan, Dallaramji, a community leader, was chatting with Professor Arun Agrawal.

'In the morning, Modaramji found seven sheep missing from his flock,' Dallaramji said. 'You ask how he knew exactly seven were missing out of more than 300? Moda knows all his sheep by name.' Agrawal smiled.

'The thought that Modaramji knew each of his 300 sheep by name seemed unlikely,' he wrote in his forthcoming book.

Dallaramji was not amused. 'Don't smile,' he said. 'Each sheep has a name, and when Moda calls, they come running.'

Agrawal wrote: 'Dallaramji demonstrated the truth of his assertion by beginning to whistle and call his own sheep by name. And several of them did come running (as far as it is possible for sheep to run), looking reproachfully at their owner at being interrupted in their browsing.'

Arun Agrawal, professor and associate dean for research in the School of Natural Resources & Environment at the University of Michigan, narrated the story of Dallaramji and shepherd's migration in his book, Poverty and Adaptation. A recently named Guggenheim Fellow, Agrawal will be using his grant to continue his research for the book, which looks at the larger picture of climate change.

"As the world comes to grips with the overwhelming threat of climate change," Agrawal told India Abroad, "we find politicians digging in their heels within their comfortable ideological turfs, decision makers thinking about the next mega-policy that will leave a legacy. And we have corporations hunting for the inside track on the big climate-related business opportunity that will build shareholder value."

Lost in the shuffle, he said, "Are the true victims of future climate change and contemporary climate variability -- the poor farmer, the disadvantaged fisher, the landless labourer, the illiterate sharecropper, and the elderly lower-caste woman; victims of emissions by the over-consuming social strata."

But are the poor just victims, he asked.

"In my research and writing, I am always aware of the need to understand how the poor have been managing the crises in their lives over the centuries," he explained. "Often we keep telling them what to do. But my project focuses on how the poor have adapted for millennia to climate impacts, and what can we learn from the poor, marginal, disadvantaged, illiterate people as they try not just with climate impacts but also the effects of the profligacy of the rich and the apathy of the powerful."

The Guggenheim Fellowship, coupled with a sabbatical and support from the School of Natural Resources and Environment will afford him the time and the space in which to complete his current project, he added.

In telling the stories of people like Dallaramji and the fight for survival of the shepherds, Agrawal is ensuring he does not offer a one-dimensional study. While his work has to be scholarly, it is also filled with vivid stories.

'We traced the footprints of the thieves two miles to the homes of the Sansis (one of the lower castes in Rajasthan) near the village,' Agrawal quoted Dallarmji. 'All of us went. There must have been at least 30 in our group. You should have heard the noise we made. A huge crowd gathered. Those (expletive) had already eaten one of the lambs. First they denied everything. Then they gave back four of the animals, and said they only had stolen four. But once we started threatening them with police their story changed quickly. I played a trick on them and asked Moda and Ranaramji to leave as if they were going to the police station. The Sansis could not take that and gave back the other two sheep, and Rs 200 ($4) for the sheep they ate. I bet that has been their costliest meal.'

The shepherds who migrate because of grass shortage also face problems from upper-caste people, who are often more prosperous.

'In the above description, the Raikas emerge more or less victorious in their conflict with a settled group,' Agrawal wrote. 'But this is not the only kind of story about mobility I learnt. Another incident powerfully brings home the dangers of mobility.

A lawmaker in Madhya Pradesh, for instance, writes to the government: "You can imagine what happens when hundreds of thousands of sheep invade your standing crops for miles. Village after village begins to weep For a whole fortnight these nomads terrorised the place. They even did criminal things like snatching money from people and bread from mothers and sisters going to the fields Last year I had about 500,000 sheep removed from my area. This year, at the time when sheep were being massacred in Dahinala, policemen, village councils, and forest officials in my area were trying to rid farmers' fields of about one hundred thousand sheep."

Mobility, Agrawal noted, "is indeed fraught with danger."

He has an MBA (development administration and public Policy) from the Indian Institute of Management and a PhD in political science from Duke University. But his first degree was in history in 1983 from Delhi University.

"I was getting very frustrated while studying history about not being able to apply it to bring about social changes," he said. He was also getting interested in the work of non-governmental organisations, and continued to study them, and also work with a few.

"There were many NGOs doing very good work," he continued. "But we lacked a comprehensive knowledge of what they were doing."

A key reason he came to America was to acquire the tools to do research on the work of NGOs, and more important, to study how people were coping with disasters and climate changes using their own resources.

Agrawal also coordinates the International Forestry Resources and Institutions network, and is currently carrying out research in Central and East Africa and South Asia.

Agrawal, who has also taught at Yale University, and his recent work has appeared in journals like Science, PNAS, Conservation Biology, World Development, and Development and Change.

He shared how he had to learn to adjust to life in America. He sought a job at IIM but could not find one. He stayed back and married an American. His parents, who live in a small village near Patna, Bihar, came for the wedding. His mother, seeing the bride in all white, was a bit flabbergasted.

"She said we wear white at death," Agrawal said. She also insisted that he had a wedding in the village.

"I did not care what ceremonies we had to undergo," Agrawal said with a chuckle, "as long as it was all over in a day. And this was the request to my mother."

He arrived in the village with his wife and four of her family. It was quite a spectacle. His uncle said, 'We have never seen a white person in our village. And now suddenly there are five of them.'

Teaching your children well

Vijay Vazirani, who has received a Guggenheim Fellowship for research into algorithmic problems in economics and game theory, is an extremely popular teacher at Georgia Tech. At least 70 students fight to be in his class, capped at 30. A student publication recently wrote that many students turn up a week after the classes started, hoping some would drop out. When asked if they have registered to be in his class, they often say they are there just to see how the class goes.

Students have often written to the school officials to say how much of critical thinking they were asked to do in his classes.

Vazirani says he does not like the old ways of teaching, taking most of the class time for drawing diagrams and making PowerPoint presentations. Instead, he introduces a concept, discusses it for 30 minutes and spends over an hour getting the students to solve the problem.

"One of the best rewards in this profession is what the students appreciate in your class," he says. There is always a conversational atmosphere in the class where students take a team-based solving approach, he adds. Students have written that the skills he encourages are very useful to them to be on the top and find good jobs even as many jobs continue to be outsourced away from America.

'I believe it is classes like Dr Vazirani's that can reverse the trend,' wrote a former student, Michael Qin. '(The course) is the key to ensuring that the best students are not subjugated to slower paced (curricula).'

Patrick Dillon, another undergrad student, noted that Vazirani 'allowed the students to speak their minds as he provided slight nudges and insights to the key aspects of the problems.'

At the surface, these problems seem to be superficial, a student's article on Vazirani in the school newspaper said. It added: 'However, as the students solve the problem, they discover gilded treasure troves, where all sorts of seemingly unrelated concepts suddenly coalesce.' By building bridges across fields, the article said, 'Dr Vazirani is able to bring out the true beauty of mathematics and convey this message to the students.'

Vazirani received his bachelor's degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1979 and his PhD from the University of California, Berkeley in 1983. He is a professor of computer science at Georgia Tech. He taught algorithms at the undergraduate level as a professor of computer science at the Indian Institute of Technology, New Delhi during the early to mid-nineties. His research career has been centred around the design of algorithms, together with work on complexity theory, cryptography, coding theory, and game theory.

"I dreamt of doing research from my high school days," he told India Abroad. "I was inspired by the likes of Madam Curie."

He said he and his brother, UC Berkeley computer science Professor Umesh Vazirani, owe their passion for research and education to their father Virkumar Vazirani and mother Kamla, a Hindustani classical artist.

'A unique man, principled to the core right from his days as a college student when he joined India's freedom struggle, he was a fiercely independent, magnanimous and deeply compassionate person,' the brothers wrote of their father who died in November at age 85. 'As a professor of civil engineering at the Delhi College of Engineering, he was loved and revered by the student community for his unstinting support in their struggles against unfair rules and an uncaring administration. Standing by his principles was simply second nature to him -- no matter what it cost him personally. A prominent memory among his friends is that he was always ready to help people in need, even little known acquaintances, without any hesitation.'

Vijay Vazirani is a passionate supporter of Akshaya Patra, a nonprofit that feeds free over 1.3 million schoolchildren in India.

"Our father was known for the absolute mastery of his subject material and the clarity with which he presented it," Vazirani said. "The values he instilled in us help us to be excellent teachers. My passion for research increased as I watched him working on technical books. He would have long, animated discussions with his collaborators who were also his friends. I felt privileged to listen to them discuss engineering. His books including Steel Structures (with M M Ratwani) and Concise Handbook of Civil Engineering (with S P Chandola) helped train generations of civil engineers in India and neighboring countries for over four decades and are in use even today."

The classical music he heard growing up in New Delhi has become an integral part of his life. "I cannot work without music around me," Vazirani said. "It can be Western classical or Hindustani.'

He lives with his Greek-American wife, and son Michel. "Like me, my wife also comes from a very old culture," he said. "And you can feel this at home. Our son who recently performed with a Georgia choir also has training in playing tabla."

Vazirani will take a sabbatical during 2011-12 to work on his Guggenheim project, titled 'Algorithms as a Lens on Economics.'

Demystifying the past, looking at the future

Years ago, the distinguished academic and Columbia University Professor Edward Said questioned the way European and American scholars looked at what they called the Orient. Now, Professor Sanjay Subrahmanyam -- a newly minted Guggenheim Fellow -- is going to study a French traveller who traversed not only the Islamic world but also the West, visiting many countries including Denmark and Ireland.

"Said wrote about the peculiar way westerners looked at the East," said Subrahmanyam, an economist and historian who is a professor at the University of California Los Angeles. "I will be looking at a number of Frenchmen, including a doctor who came to India in the 17th century. I am also looking at the way the French traveller looked at foreign countries in Europe and how he evaluated the Islamic countries.

"I often work with other scholars simply because Indian history is a vast area, and it is better to have a scholar who is an expert in another area work with me," he added. "But (on) this project -- which would result in a book -- I will be working on my own."

He teaches courses on medieval and early modern South Asian history; the history of European expansion, the comparative history of early modern empires, and world history pertaining to Asia. In 2002, he was appointed as the first holder of the newly created Chair in Indian History and Culture at Oxford University.

Subrahmanyam, who holds the Navin and Pratima Doshi Chair in Indian History and is founding director of the UCLA Center for India and South Asia, will conduct research for his book in France and Italy to study archival manuscripts and published texts in many languages. Born in New Delhi, he earned his masters' in economics from the University of Delhi. He received his PhD in economic history in 1987 at the Delhi School of Economics. From 1983 to 1995, he taught at the Delhi School of Economics.

He said his new book Three Ways to Be Alien -- being published by Columbia University Press -- offers the story of 'floating identities in a changing world.' He has studied the lives and writings of a trio of marginal and liminal figures cast adrift into an unknown world: A 'Persian' prince of Bijapur (in central India) held hostage by the Portuguese at Goa; English traveller and global schemer Anthony Sherley, whose writings reveal a nimble understanding of realpolitik in the early 17th century; and Nicolo Manuzzi, a Venetian chronicler of the Mughal Empire in the later 17th century who drifted between jobs with the Mughals and various foreign agencies, observing all but remaining the eternal outsider.

Subrahmanyam has said that writing 'readable' -- accessible and appealing to the lay reader -- books on history is 'a complicated issue.'

'First of all,' he said, 'no doubt readable and accessible books of popular history should be written, not only in English but in other Indian languages But they need not be conventional biographies of monarchs and great men, which are often just potboilers Second, such readable books cannot replace or do away with the proper academic monograph, which is based on textual or archival research, and can't be read that easily by non-academics -- or even given to your family members as a gift. Once in a blue moon, a book comes along like The Cheese and the Worms by Carlo Ginzburg, which does both things -- the rigours of research, and total accessibility. But this is not very often.'

As the founder director of the UCLA Center for India and South Asia and as a professor with an endowed chair, Subrahmanyam said, he is often challenged by a section of Indian immigrants in America. Some want him to fight with historians -- Indians and non-South Asians -- whose views they do not like. Many of them are not aware of the breadth of scholarship about India across America, he says. He has noticed over the past two decades a distinct growth in Indian history being offered at many campuses not only on the East and West coasts but also on smaller campuses in the Midwest.

"There is no central ideological line being pushed here," he said. "But there is a hysteria in some Indians. There are some who believe everything is done by Marxists; and then there are those who do want Americans -- and by extension 'foreigners' -- to do any work on Indian history, philosophy or religion that they can approve of."

The objectors, he said, often have "an exaggerated sense of national pride," and some have a guilt complex of having left India.

Guggenhein Fellowships: A prestigious achievement

The Guggenheim Fellowships are awarded annually to artists, scholars and scientists, based on past accomplishments and future promise. This year's 180 fellows are "the best and the brightest" of a 3,000-applicant pool, said Richard Hatter, a spokesman for the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation.

Each recipient gets $40,000 to $50,000 in grant money. The fellowships, as per the foundation, 'are awarded to men and women who have already demonstrated exceptional capacity for productive scholarship or exceptional creative ability in the arts.'

Among the previous fellows are poet Langston Hughes, novelist Vladimir Nabokov, scientist Linus Pauling, playwright Wendy Wasserstein and photographer Ansel Adams.