'Ideally, children should go to a university if they know what they want to gain from it, not because everyone else is going.'

There has been an explosive growth in the demand for international curricula and syllabi in India during the last decade.

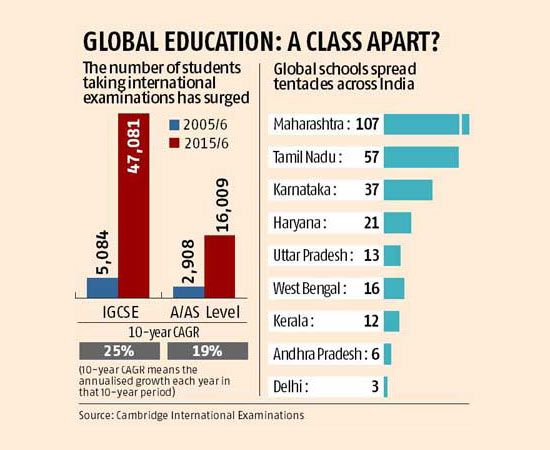

With this trend picking up, international examinations like the Cambridge International Examinations (CIE) A levels (taken at age 18) and IGCSE or International General Certificate of Secondary Education (taken at age 16) are gaining currency and the numbers tell the story (please see chart).

Between 2005-2006 to 2015-2016, the compound annual growth in the number of students taking the IGCSE is 25 per cent and for the A levels it is 19 per cent.

Between 2005-2006 to 2015-2016, the compound annual growth in the number of students taking the IGCSE is 25 per cent and for the A levels it is 19 per cent.

CIE's global Chief Executive and an Oxford University alumnus, Michael O'Sullivan, left, 57, spoke to Anjuli Bhargava.

How do you deal with the quality of teachers -- teachers in India are generally not equipped to teach these syllabi?

There is an acute shortage of highly qualified and quality teachers -- not only in India -- but definitely in India.

There is even a greater shortage of teachers who are skilled in teaching international curricula such as ours. A big and growing part of our work is teacher development.

In the 360-odd schools we work with, teachers will receive training in both how to teach their subject in an effective manner and in general teaching skills.

Last year, we did 50 face-to-face events for teachers here in India.

This will double to 100 this year. There are big shortcomings in the way school education -- all over the world -- is designed and delivered.

In most organised schools, when we find students listening to the teacher, can we assume students are learning? Our research says no.

They might be learning nothing. Or we may go to a progressive school and feel the students are engaged, having fun but does it mean they are learning?

Again, the answer is not necessarily a No. They might be playing games they enjoy, but not learning anything new.

We know that students learn when they think. When they don't think, they don't learn.

Most of the time, in most schools, most students are not thinking.

They are doing something else so they are not learning much. \

So there is a huge opportunity globally to improve the outcomes by better designing the curriculum, assessment, and teaching.

How do you know children are not thinking most of the time?

Experienced observation of teaching by good teachers is the best way to do it.

Our experience shows that the best schools are those where the principal gives top priority and time to instructional leadership.

The symptom of a school that is going nowhere is a principal who mostly worries about the new building or the business of the school or communication with parents or the final results.

A school principal has many responsibilities, but our experience shows that schools where the principal allocates most of their time to instructional leadership -- that is they are concerned about what teachers do in class and what students do in class -- fare the best.

Is university education in the UK going through a similar squeeze like the US... people questioning the value of degrees and so on...

There is a trend of questioning the cost of higher education in the UK and scrutinising the benefits.

UK universities have been quite successful at diversifying what they offer. Many universities have made their degree courses employment-relevant.

Is it true companies in the UK are beginning to value apprentices at times over graduates?

I have noticed that as well. It does seem to me social habits are formed in the UK and some other countries where going to university is considered an end in itself.

In fact, going to a university should only be important for what you get out of it.

I see the same in middle-class India. This is not ideal.

Ideally, children should go to a university if they know what they want to gain from it, not because everyone else is going.

China is a case in point. The country has huge skill shortages and significant graduate unemployment.

University courses are not preparing the students for the opportunities that exist.

Is there a move towards MOOCs (massive open online courses) -- like in the US?

They are much talked about. But I have to say I am quite sceptical. I don't think anyone really knows how to make MOOCs work as a business model.

Drop out rates are extremely high. I think MOOCs -- like Beta Max -- are an important step in the evolution of online learning, but I don't think they are an end point.

At any stage?

I look at the evidence and based on that I don't see MOOCs becoming an established end point.

One of things I have noticed in education, quite often when a big idea comes along, people begin to talk about it like it were already successful, but they tend to forget that they are actually discussing an idea.

It's like a company trying to sell shares based on its business plan.

If I were buying shares, I wouldn't look at the business plan as closely as the accounts.

At the moment, I have to say that MOOCs are not a proven success, even though they are quite exciting.

Let me say it is more convincing to say traditional models of higher education will change.

It is also fair to say that digital technologies will play a big part in that change. But it is less convincing to say what will replace it.

And further let me add that it is not always the best ideas that win.

The global standards -- as we have seen in the past -- are not always the best standards; yet them become global for extraneous reasons.

Lead image only published for representational purposes. Photograph: Kamal Kishore/Reuters

© 2025

© 2025