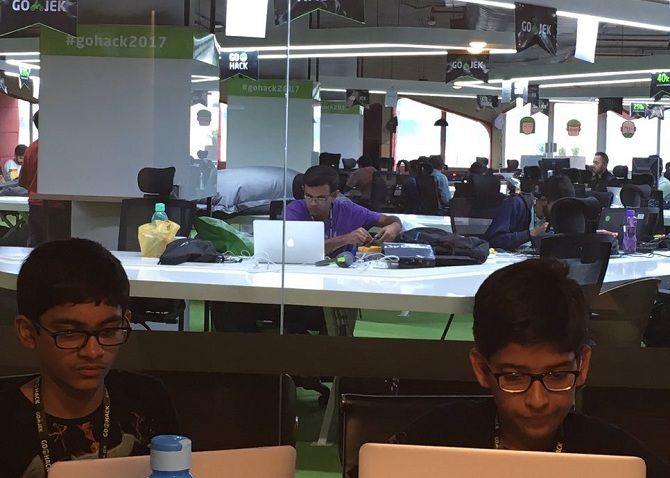

At a hackathon organised by Indonesia's GO-JEK in Bengaluru, there were over 100 people working on their projects. Most were between the ages of 25 and 30. All except the CoderDragons: Mrinal Jain is 11, and Shreyas Katuri is 12.

Nikita Puri meets the pre-teens from Bengaluru who are building a virtual voice assistant named Erica.

In Mrinal Jain's room, his mother holds up what looks like an open electrical circuit on wheels.

"This was a Bluetooth-enabled car I programmed in a way that you could control it using a cell phone," says Jain as he gazes at the piece lovingly. Now dysfunctional, wires sprout out from it in all directions.

"I am going to modify it in such a way that it'll move on a black line drawn on the floor," he says.

Jain's interest in robotics is only parallel to his new-found love for coding, a passion he shares with his friend and classmate, Shreyas Katuri.

In accordance with their school curriculum, their batch of sixth-graders at Bengaluru's NationalPublic School in HSR Layout is learning Microsoft Excel, but Jain and Katuri prefer to swap notes on programming languages and checking the codes the other has written. Even their lunch breaks are spent discussing how to take their pet projects -- a host of coding-related experiments -- to the next level.

Over the last one week, Jain and Katuri have often explained to their school teachers what a hackathon is.

"Some of them thought it was something about hacking into a website. It's not; it's about finding a hack and finishing a project in a given period of time," says Katuri.

At a hackathon organised by Indonesia's ride-sharing, payments and logistics start-up firm GO-JEK recently in Bengaluru, there were over 100 people working on their projects. Most were between the ages of 25 and 30.

All except the team that called itself CoderDragons: while Jain is 11, Katuri is 12.

GO-JEK had received well over 2,000 entries and 300 applications for the hackathon, and CoderDragons was one of the 52 teams selected from these.

Both Katuri and Jain wear black-rimmed glasses, are lanky and talk with utmost passion about Artificial Intelligence and machine-learning. They could easily pass off as brothers at first glance.

It's primarily a love for technology that has brought the duo together.

At the hackathon Jain and Katuri started work on Erica, an automated application, or a bot.

An interactive and virtual voice assistant, Erica is being designed to help one place orders online, especially when one can't use the phone, while driving for instance, or if one is visually challenged. The CoderDragons are starting out by programming it for food-delivery services ("specifically pizzas," the boys chime in with wide smiles).

The CoderDragons still have a long way to go before Erica hits the market, "but it's not really about Erica," says Swaminathan Seetharaman, SVP, GO-JEK Engineering India. "It's about the spirit of what they are trying to achieve. These boys are fearless. This hackathon was designed for experienced coders but they were not at all intimidated by them."

Erica is more like Amazon's Alexa than Apple's Siri, says Jain, since the former can actually place orders.

When in his room, Jain places a laptop on the lower half of a bunk bed. A stuffed tiger, fun-sized trucks and cars, and dinosaur toys look on from a side-shelf as he demonstrates how Erica works.

"What would you like to order," asks the program when Jain opens it. Much like others like it, Erica's voice is robotic and female.

"Pizza," answers Jain.

"What kind of pizza would you like?" asks Erica, before she goes on to list a selection the boys have programmed in.

Jain's projects themed around robotics, like the Bluetooth-enabled car, are often sandwiched between piano and tennis lessons, coding, and voracious reading. After wrapping up books by Stephen Hawking, Douglas Adams and Arthur Conan Doyle, he hopes to move on to Isaac Asimov.

The fact that much of the human brain is still shrouded in mystery fascinates the 11-year-old.

And when the children are inquisitive, parents are the first to receive a barrage of questions.

"He has always been very curious. He'd regularly stump us with questions we didn't often have answers to, like questions on space and time and quantum physics," says Jain's mother, Parul, a software architect. "He has grown up on encyclopedias and had an understanding of what photosynthesis was and how machines work years ago."

She remembers how last year Jain began to show an interest in the idea of storing memories online.

Just a few days ago, Jain reached out to a Harvard researcher who works in the field of neural networks. "I want our minds to directly control computers. That way everything we see and experience can be stored online. We'll never forget anything," he says, hoping he'll hear from the researcher soon.

Just about a year ago, before Katuri began coding, his parents were a little surprised when they found their son staring at a black screen.

"Initially we thought he was just changing the wallpaper but then realised that he had been trying out coding on his own," says Shyam, Katuri's father and an operations' specialist in an e-commerce firm.

At the hackathon Jain and Katuri started out with a widely used visual-programming language called Scratch sometime last year, but now in between they know Python, Ruby, C#, some Java, JavaSrcipt and C++, among others.

There's no rush in building Erica, says Jain.

"My father told me that Intel had to once recall its chips because of a bug. Recalling something can be very tough and we don't want that to happen with Erica; we'd rather take time to build it than rush into deadlines," he says.

After Erica is built and put up on a server online, the duo hopes to tie up with companies and offer the voice-assistant's services, says Katuri. Alternatively, when ready, Erica can also be put on Google and then moved to the iOS store.

Katuri is inspired by the life stories of Apple's Steve Jobs, Google's Sundar Pichai and Chinese business magnate Jack Ma. "These guys never gave up, like Jack Ma was rejected by Harvard 10 times," says Katuri.

When Katuri signed up for the hackathon with Jain, his parents weren't even aware of it.

"He would harass Siri all the time. He'd keep asking the application all sorts of questions and looking at how much data it throws up. That's when he realised that there was no functionality and that Siri just helps replace text with audio," says Shyam, Katuri's father.

For his last birthday, all Katuri wanted was more books on programming, recalls his mother, Rinku.

"It's very exciting to see the kind of enthusiasm and interest Shreyas and Mrinal have at this age," says Seetharaman. "They have the maturity to understand feedback and make changes accordingly."

The coder boys have also been invited to be a part of the Facebook Developer's Circle, a community that brings software developers together for meet-ups and hackathons directed at accelerating technological advancements.

"These boys are builders, they just needed a platform," says Nelson Vasanth J, lead of the developer's circle and founder of Startup Mechanics and Honey Technologies. "They are sure to push the boundaries of technology and come up with something amazing in a year or so."

© 2025

© 2025