| « Back to article | Print this article |

Inside Istanbul: 'The greatest city' in the world

The city of Istanbul is easy to fall in love with. Kushal Chowdhury was the latest victim.

My first vivid recollection of the Bosphorus is, strangely, not of the first time I saw it. I know, of course, when I did see it the first time -- on the bus from the airport to our hostel in Sultanahmet -- and it must have been as majestic and as resplendent as ever. But try as I may, I cannot recollect this image. It is, perhaps, lost in the labyrinths of my memories forever.

There is a story in here somewhere, of a man lost in a maze of his own memories in a quest to find a particular image -- a story that a Borges might have fancied.

It is the view from the rooftop cafe of our hostel that I do recollect. A warm sunny July afternoon. The red chequered table cloths. The beer (Efes).The quaint white-gray houses that lead up to the waters. The vast muddle of buildings on the far side, indistinguishable from one another.The occasional dome and minarets of a mosque. Sea gulls. Everything in shades of gray.

In Elif Safak's delightful novel The Flea Palace, a character muses about how her memories, of every city she's been to are, defined by a particular colour. Except Istanbul. Istanbul, she says, is devoid of a defining colour. In that moment, taking in the city as it spreads around me, I understand what she means and yet, disagree with her.

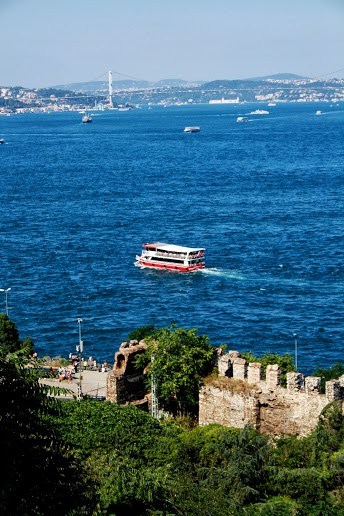

For right through the middle of these muted shades, flows the legendary Bosphorus. It is just as I have imagined for all the years since I first knew it existed. Its famous waters sparkle in the afternoon sun -- turquoise and white and turquoise again -- a gentle shimmery haze hangs over the many boats and yachts and sea vessels that bob over it. If this cannot define the colour of a city, nothing can.

Inside Istanbul: 'The greatest city' in the world

I travelled to Turkey for ten days with two friends in July 2011. Now, almost a year later, reading about the turmoil the country is in at the moment, my mind, invariably, takes me back to those ten days and it occurs to me that I must document them as best as I can, before more images slip away into that unforgiving labyrinth like the first view of the Bosphorus has.

As I write, I realise that I recollect a great many scattered images in glorious detail while large chunks in between have gone missing. I suppose it is comforting to presume that the brain intuitively retains only the best and the most important bits, but really, can one be certain?

I remember, for example, a mundane breakfast in one of the many by-lanes that thread their way through Istiklal Avenue. It isn't our first day in Istanbul. We are in a cafe; the tables are set outside on the street. We eat what we have throughout the trip -- simit (ring-shaped bread with sesame seeds) with cheese and tea (cay in Turkish; pronounced chaai).

There are two old men sitting on chairs set out for them next to us. They share a newspaper and a cup of tea. There is no table laid out for them. They are regulars. The street is quiet and peaceful at this hour. I remember sounds – the swishes of brooms, the unseen scooters on another street and the sirens of ferries. Why do I remember all this?

Istiklal Avenue, incidentally, is right in the eye of the storm that Turkey faces today. It is where the fiercest protests have been. It is where the voices against Erdogan are the loudest.

From having spent several hours there, it is not hard to understand why this must be the place. It is in Istiklal that Istanbul is at its most modern, most liberated -- or most 'western' if you like.

I am trying to remember the first evening of revelry in Istiklal. It is easily one of the most memorable evenings of the trip, indeed one of the most memorable of any trip. A flurry of bright images appears, out of sync, but the disjointed nature of the recollections is probably more to do with all the raki we drank than natural erosion. From them, I piece together, what I suppose, is a chronological sequence of events.

Inside Istanbul: 'The greatest city' in the world

We have spent the day visiting the main tourist attractions of Istanbul -- The Topkapi Palace, The Blue Mosque, The Aya Sofya, and The Basilica Cistern. They are all overwhelming structures, each of them; it is impossible to not be overawed by their grandeur. But like most tourist attractions anywhere in the world, they have long become limited to that identity. They teem with foreign visitors and profiteers and the discordant sounds of several languages spoken all around at once.

All of this cannot take away from the splendour of the architecture and the building themselves, but it robs them to a great extent of the unique sense of place and feeling they could evoke in the centuries gone by. As an outsider, the feeling one is left with inside The Aya Sofya or The Blue Mosque is exactly the same as if one were in the St Peter's Basilica in Rome.

Inside Istanbul: 'The greatest city' in the world

And so it is that we head to Istiklal for the evening, having been simultaneously awed and underwhelmed by what we have seen during the day, with high hopes of an exuberant evening. My cousin, who is incidentally in the city for some months as a visiting faculty at the local university (Man, how I hate him!), has assured us that there isn't a better place to be in after the sun goes down.

He meets us at the Sultanahmet end of the Galata Bridge near the Grand Bazaar. We walk on the bridge over to the other side as the sun sets, the inimitable Istanbul skyline behind us. On both sides of the bridge, we see hundreds of men -- tourists and locals, rich and poor -- fishing. Their fishing rods are placed on the parapet, the lines plunging to the water below. Next to each man lies a basket or a vessel to hold the day's catch. It is a unique sight.

The bridge deposits us into Karakoy (Galata district; for the football minded, this is where Galatasaray belongs) from where the Tunel -- a two-coach shuttle train inside an underground tunnel -- takes us to Istiklal.

An astonishing range of colours and lights and smells greet us. There are neon lights of every conceivable colour; the shops on either side, the quarters over them, the spaces between them -- they are all covered in these lights. The street itself stretches out ahead of us and although it is only a few kilometers before it opens on to Taksem Square, just then it makes us believe that it never ends.

All around us there are food stalls and restaurants and cafes and pubs and Turku bars (dimly lit spaces with live Turkish music). Somewhere in the middle of all these, there are the unavoidable McDonald's and Subway; we are grateful to find that they are both nearly empty.

Inside Istanbul: 'The greatest city' in the world

On the street, there are hundreds of thousands of people, walking. They scarcely pay any heed when the famous antique tram passes through, perilously close. They step aside at the last moment to allow the tram to pass and it is only in those instants that the tram lines on the street are visible. There aren't many people on the tram; people are happier looking in from the outside than the other way round.

We start with a Turku bar. Inside, a lady and her troupe sings for the customers. Her voice is boisterous and interspersed with exaggerated quivers and the main accompanying instrument is the baglama (or saz -- a Turkish version of the guitar with seven strings), both of which are in line with what we have seen in Fatih Akin's enchanting film on Istanbul and its music Crossing The Bridge: The Sound of Istanbul) and we are, therefore, absolutely thrilled and speak of Sezen Aksu in barely constrained voices. We drink Raki -- Turkey's own aniseed flavoured drink -- from tall glass flutes. My cousin explains to us the ritual that goes with drinking Raki -- two flutes, one filled with raki and the other with cold water, a sip from one and then the other, and enormous plates filled with fruits and sometimes some form of meze. They have built rehydration into the ritual, he tells us. If one were to adhere religiously to it, no amount of binge drinking would lead to terrible mornings after.

Soon, people on other tables get up and start dancing and swinging and singing along.

Much drunken merriment ensues.

Inside Istanbul: 'The greatest city' in the world

We leave the joint near midnight. The street, it appears, is even more crowded than when we left it. We eat Dolma Kebaps (one of the great joys of travelling in Turkey are the innumerable words that one recognizes from Hindi) at a busy, cramped restaurant; they are delicious. There's also Ayran, which is basically buttermilk, and Baklava. The Baklava is so heavy it could easily pass for the main dish.

We head for our hostel in the small hours. At no point, during all of this, have the lights dimmed or the crowds thinned.

I remember our journey on the ferry to Kadikoy, a well-known district on the Asian side of Istanbul. It is late afternoon but the sun is still potent and a long way from the horizon.

We sweat though a cool breeze from the sea blows in occasional gusts. Istanbul's skyline, apart from the tallest minarets and the Galata Tower, is hidden behind a haze. At the time, I still believe we will climb the Galata tower at some point; we never do. We are seated in a row, the three of us; the sun is behind us and the two old ladies with scarves across us squint continuously due to its glare. Next to them sits a young man, likely in his early twenties. He asks us where we are from and by and by we are engaged in conversation.

He speaks half-decent English. He is studying film at a school in Izmir, we learn, and immediately hound him for the names of Turkish filmmakers.

We mention Nuri Bilge Ceylan (he is thrilled that we know of him and teaches us to pronounce the name properly) and Fatih Akin. Fatih Akin is German, he states quietly. He recommends other names we do not know of -- Dervis Zaim and Zeki Demirkubuz. In the year that has since passed, I have seen films by both men; they are brilliant.

I do not remember a great deal of detail of the hours we spent in Kadikoy, except a half hour we spent in a cafe. It is on a little known street, where we spend a half hour sipping tea.

The place is a cluster of tables with green velvety tablecloth and on most tables, old men sit and play cards. Their attention scarcely strays from the cards they have been dealt and even when they pick one and flick it carelessly on to the table, their eyes are glued unwaveringly to the ones that remain in their possession. Their teacups are never empty. A large man refills them every few minutes; nobody on the table notices him do so.

There is a particular moment there that has stayed with me -- a man about to throw a card on the table and the large man serving tea standing between him and the window behind just so a shadow covers the player but not his card (a seven of spades, I think, though I am unsure if my memory can be that precise).

Inside Istanbul: 'The greatest city' in the world

We take the ferry back near sundown, and this time, the domes and minarets and everything else form silhouettes against a gradually darkening orange sky. The waters of the Bosphorus are no longer turquoise; they too reflect the sky's orange. Some of our best pictures of Istanbul are from then.

Is it then that our memories are slave to the pictures we take? I wonder while I write. Is it then that the fact that I remember so much of certain passages and nearly nothing of others is merely a product of the pictures I have or have not taken?

I haven't a single photograph of the Bosphorus when I first passed by it. But I remember so much else that is not captured in pictures, that can perhaps not be captured in pictures.

I remember searching desperately for ways to grasp the concept of Huzun, as I have imagined it, from reading Orhan Pamuk's fascinating memoir on Istanbul. Pamuk describes 'Huzun' as it applies to the residents of Istanbul -- as individuals and as a people. 'Huzun', he explains, is a Turkish word, without a precise English equivalent; it defines a state of mind in which one experiences a melancholy that comes from a mixture of great spiritual loss and hope. Istanbul evokes it, according to Pamuk, through the awareness of its glorious past and the realisation that the city's greatest era is, perhaps, left behind forever; a forlorn pride that the people of Istanbul experience throughout their lives.

Although I have spent hours in the neighbourhoods Pamuk actually describes -- Cukurcuma, Cihangir, etc -- it is, in fact, in Kadikoy that I recall sensing this feeling most palpably -- perhaps because the old, short buildings, red-gray and decrepit, the damp streets, the old people gathered in cafes such as the one I just described and a general sense of artsy decay remind me of Kolkata -- a city that I believe will understand and embrace Huzun as much as Istanbul does.

It is a great city, Istanbul -- to me, the greatest city I have seen yet. The sights are breathtaking. The people are warm and friendly. The women are gorgeous. The food is sumptuous. And the memories of it still left to me are incomplete and haphazard but filled with indelible images and cheerful vagueness.

And there's the Bosphorus.