| « Back to article | Print this article |

English Vinglish: India's other half that struggles to keep up

India has 22 official languages and many more that are not officially listed. All Indians speak any one or two of them.

But the language they really need to be fluent in is an imported one -- English.

Historical compulsions have made English India's lingua franca. Yet, maybe only a quarter of Indians, or less, speak it with any degree of fluency.

Research shows that more than half of about five million students who graduate from universities each year are unemployable for various reasons.

One of those reasons is the inability to string together a coherent sentence in English.

As the Indian public education system struggles to produce English-speaking professionals, private training institutes step in and promise to fulfil the dreams and aspirations of young women and men who need the language to get good jobs.

A look at India's 'other half' that labours hard to not get left behind.

***

Mehjabin Mirza struggles to speak in English. She grinds her teeth, clenches her fists; her facial muscles contract. It is as if her physical self is resisting uttering English words. The kerchief in her hand has been twisted and crumpled into a ball.

After much struggle, she resorts to speaking in Hindi:

"Har roz centre ke saamne se aati-jaati thi. Roz sochti thi aaj join karoongi. Mahinon aise chala. Magar main himmat nahi juta payee. (I'd walk past the centre every day. Every day I would promise myself I'd enrol for the classes. This went on for months but I couldn't muster the courage)."

Mirza works for a beautician in central Mumbai. Her clients are primarily young women from upper class housing societies around her workplace.

So far she has been getting away by speaking Hindi with them. But a part of her 20-year-old self looks at her clients and aspires to be like them.

She may never have the kind of money they do. The closest she can get to their lifestyle is to speak like them. In English.

Less than a month ago, after much hesitation Mirza took her first step. She joined the local branch of Speak Well, a prominent chain of English speaking classes.

Mirza says she's learnt English in school. She understands the language but cannot speak it. "It was all rote learning. After a point I lost interest," she says in Hindi.

Every morning, before she goes to work, she stops by at the centre for a 90-minute lecture. She still struggles to speak but she says she will get there.

***

Durga Chaurasia works for a stock broking firm. Like Mirza, English was part of his school curriculum. But he is now taking English lessons.

He starts his day at around 6 am, reaches the centre for a 7.30am lecture and then heads to work.

"No one told me to (join a class). But knowledge of English helps," he says, struggling to put together the sentences. "It will help me start my company some day."

English Vinglish: India's other half that struggles to keep up

Mehjabin Mirza and Durga Chaurasia are products of a public education system that is struggling to keep up with not just classrooms bursting at the seams, but also a fast-changing world that demands a lot from it.

As a result, they have no option but to seek help from private coaching classes such as Speak Well.

Speak Well claims to be Mumbai's 'No. 1 training institute' and is the brainchild of Mahesh Joshi, an entrepreneur who has been in the training business for as long as he remembers.

Joshi's two earlier ventures -- computer training and placements service -– didn't do well. With the latter, he realised that he had to make his clients employable.

And one way to do that was make them fluent in English.

"That was when we started SpeakWell," he says. "We hired (qualified) people to design the course material and started out in 2006. In a year, we expanded and had 11 centres."

Joshi may not claim to be the most eloquent speaker of the language, but he employs over 640 people across 70-odd centres.

By his own admission, Joshi caters to the bottom of the pyramid. The result?

"Close to two lakh students have graduated from the time we started," he says.

***

Hasib Ahmed is one such student.

After completing his course, he taught at one of the centres for some years before deciding he had to start one himself.

Ahmed runs English Today, a tiny English training institute that doubles up as a coaching class for school students in Dharavi, that large enterprise-rich slum of Mumbai.

When he was young, he studied in a Hindi medium school. He graduated from college with a degree in history and political science, in Hindi not English.

Instead of joining his father's textile business, Ahmed went to Saudi Arabia where he taught Hindi to students at a private school.

He returned for a vacation, got married and "didn't have the heart to leave my wife and go back. So I stayed in Mumbai," he says.

He borrowed Rs 12,000 and joined a 12-day train-the-trainer programme at Speak Well. Soon after, he bagged a job with the institute.

He now has a language centre of his own.

Hasib Ahmed speaks the language with some difficulty. He stammers, hunts for words and frequently switches to Hindi. He doesn't take classes often.

That job seems to have been outsourced to Kusum Madhur whose English seems far superior to his own.

Madhur also doubles as a receptionist and a counsellor. It is her job to convert the enquiries into admissions. She is also the first point of contact for walk-in customers such as Roopa Kumari Sharma, a newly-wed bride who is now sitting across the table.

"Bank mein naukri milegi? (Will I get a job in a bank)?" asks Sharma who is accompanied by her husband, a daily-wage labourer. "Magar humne Commerce nahi kiya. (I haven't studied Commerce)."

Madhur assures her that she can indeed get a job in a bank. And it doesn't matter what she has studied as long as she pays up for the course and completes it.

Ahmed watches silently as Madhur closes the deal. She has convinced Sharma to start the very next day and pay half the fees in advance.

"They would have paid the entire amount. You should have asked," Ahmed says.

Madhur isn't very perturbed. She tells her boss that they'll pay up before the end of the month.

English Vinglish: India's other half that struggles to keep up

In India, learning English is quite unlike learning any other foreign language. For one, English isn't exactly 'foreign'.

You also don't learn English as a hobby. You learn it because you don't have a choice.

Ram Avtar Gupta and his father had realised this way back in 1976 when they released the first edition of Rapidex English Speaking Course. Since then the book has been reprinted so many times that Gupta has lost count.

Today it is the flagship brand of Gupta's publishing house, Pustak Mahal. It is also, he claims, one of the most pirated books.

After some probing, he reveals that the Rapidex English series sells more than a million copies each year. Of these 500,000 copies are of its Hindi-to-English edition alone.

(To put it into perspective, as of April this year best-selling author Amish Tripathi's Shiva Trilogy had sold 1.7 million copies in two-and-a-half-years.)

"Initially it was seen as a language of the rich. It is no longer the case. I have known auto rickshaw drivers buying copies of our book. English is the language of the masses. It is a necessity. Without it there are no real job opportunities," Gupta says.

***

Mohammed Alam has a job.

He is the head chef at a major restaurant chain in Mumbai. At 32, it isn't a mean achievement. Yet when he sits in on presentations or has to decide menus written in English, Alam is at a complete loss.

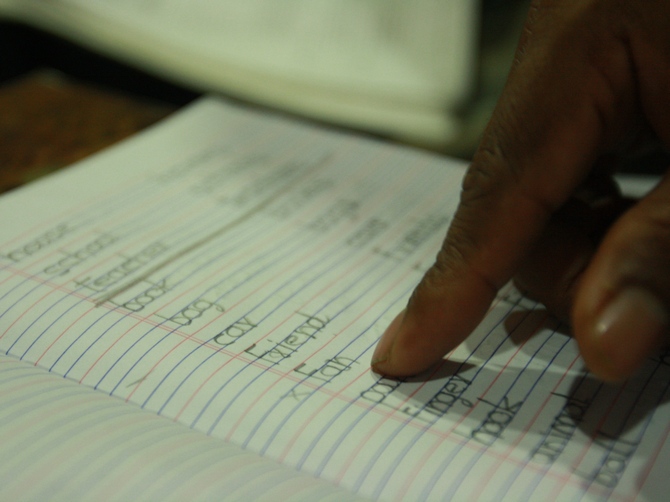

So after his shift, Alam heads to English Today where he cowers in a bucket seat and goes through the list of words like a five-year-old would:

c-u-p: cuffs

t-a-b-le: tables

s-o-u-p: soofs

Alam's trainer, Kusum Madhur, corrects him:

"It is cup, table, soup…" she says.

Alam says it right once and then goes back to pronouncing it the way he'd been doing.

It is a struggle he admits but he is at it.

Others in the class include a housewife who finds it embarrassing to attend her children's open house, a teenage girl who wants to find a better job and another boy who hopes it will help him build the confidence to approach girls.

Their refrain is the same: 'We know the language but we cannot speak it'.

The classrooms of English Today and Speak Well are in many ways a microcosm of our society.

While employers struggle to find qualified candidates, millions of young women and men are unable to find jobs.

According to a Bloomberg report, over a million Indians enter the workforce every month and these figures threaten to only get worse in the coming two decades -- the crucial period during which policy makers are hoping to cash in on the 'demographic dividend' of its sizeable youth population.

The employability solutions company Aspiring Minds in its survey points out that less than half of about five million students who graduate from universities each year are employable.

Around me in the room, I am looking at that majority as it struggles to pronounce monosyllabic words. Either they studied in a different language, or they were taught English by teachers who can barely speak it themselves.

English Vinglish: India's other half that struggles to keep up

It is past 9am on a Tuesday morning. Saket Koli is packing his bags to leave for work at the end of his lecture at a Speak Well franchisee.

Koli is 28 and works for a large software company.

When he is travelling, Koli spends his time reading on a new e-book app he's downloaded. Currently, he's reading Sun Tzu's The Art of War on his phone in part because it's available for free and also because "it just helps to familiarise yourself with the language".

Koli's biggest hindrance is the American accent. "We have American clients. I just don't understand what they say!" he says incredulously.

He's preparing though. Every night he tries to squeeze in an American film that's playing on television. He tries to familiarise himself with the accent. The subtitles help him a great deal.

"Eventually I hope I am able to understand the entire movie without the subtitles," he says.

Koli's favourite movie series is Rocky.

"I've watched all of them," he says, "I like Rocky. He struggles. Just like me."