| « Back to article | Print this article |

Why Cameron's promises to Indian students don't cut ice

Britain needs to control unskilled immigration, but extant rules dissuade even the 'best and brightest' of students that it seeks to attract.

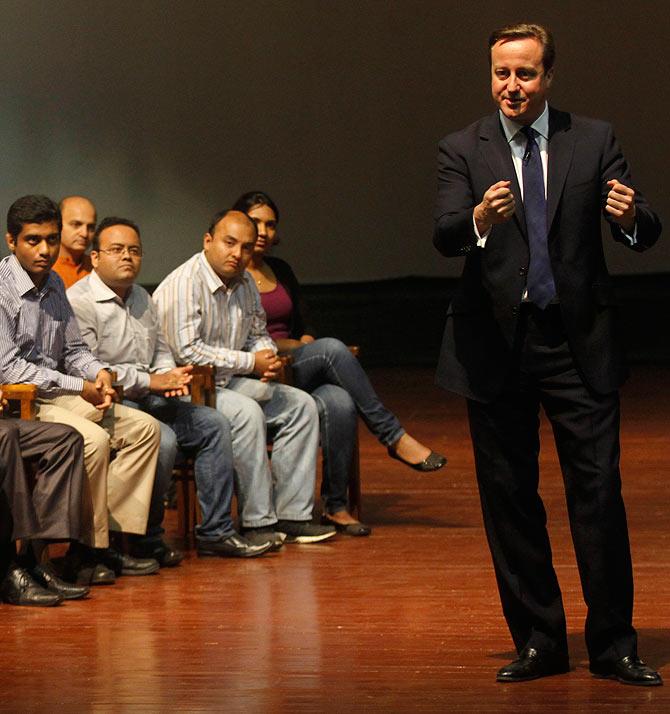

David Cameron's 'hurricane' visit to India was pretty much ignored on primetime TV, with the Indian media preoccupied with other domestic issues entirely (read: Sachin Tendulkar, more unparliamentarily speeches and more campaign mudslinging).

This is the third time the enthusiastic British Prime Minister called upon his Indian counterpart since he took office in 2010; for the most part to seek a boost in bilateral trade ties between the two nations and pitch for more opportunities for British companies in India's markets.

India and Britain under Cameron have tried to make reasonable headway in their relationship which has, while moving beyond the shared history of the British Raj, India's fascination with British royalty and Enid Blyton and Britain's fondness for curry, still fallen short of being noteworthy in the context of the 'special bond' the two nations claim to share.

Trade has languished at $12-15 billion in the last three years, down 5.21 per cent in fact, between 2011-12 and 2012-13 and Britain doesn't even feature in the list of India's Top 10 trading partners.

There are however more than 900 Indian companies operating in the UK, Britain is India's third largest FDI investor as per cumulative flows between 2000 and 2013 and Cameron has held that bilateral trade is on track grow to $37 billion by 2015.

Britain is also pushing for the Indo-UK free trade agreement (FTA) to be swiftly concluded and joint cooperation on a Mumbai-Bangalore Industrial Corridor is under discussion.

There is sufficient reason to believe progress will be made on these fronts. But the one area where there is a growing dichotomy between rhetoric and reality is in the area of immigration and education.

While the UK has scrapped the £3,000 visa bond for Indians, there is much to be accomplished if Britain were indeed to walk the talk of opening floodgates to Indian students and migrants.

"There is no limit on the number of people that can come and study at British universities." Cameron claimed. "They've got to have an English language qualification; they've got to have a place at university… There is not a limit on the numbers who can stay afterwards, so long as they are in graduate employment" he told the UK's Express newspaper.

But Indian students listening to Cameron's pitch say the ground reality is quite different.

Anirudh for instance, has just returned to India after completing a Master's degree in Computer Science at a Scottish university.

He tried getting a job in the three months available before his visa was to expire, but wasn't lucky enough to find one. Had the UK's visa regime been less stifling, he says, he would have been working in Britain today.

"I don't think I got my money's worth. After spending Rs 15 lakh, I had hoped to stay back and recoup some of that investment by working and getting international experience."

In 2012, the post-study migrant work visa which allowed Indian students to stay on after their degree for a further two years to find work, was scrapped.

What's more non-EU students wanting to find a job in the UK now have to switch to a Tier 2 visa, for which they have to qualify for employment under the points based system, and find a job which pays a minimum of £20,000. With a window of no more than three months open after university, this is difficult to accomplish, say students.

No wonder then, the numbers of Indian students going to the UK has tumbled by 25 per cent in 2012.

Mr Cameron of course, has only responded to domestic pressures to cut immigration, and stop rampant abuse of the system. But in doing that, he's also scuttled the bid to attract the 'best and brightest' from India whose students contribute millions of pounds to British universities every year.

Cameron faces a duel dilemma -- quelling an anti-immigrant sentiment at home, whilst gesturing a positive, welcoming message overseas that would change perceptions that Britian was closing its borders to Indian immigrants.

Unfortunately, the past year has seen the debate around immigration heating up in the UK, with former home secretary David Blunkett recently suggesting that the arrival of immigrants from Eastern Europe could lead to riots on the streets of London.

Jack Straw, another former Labour home secretary, admitted his party made a "spectacular mistake" loosening immigration for European migrants under the last government.

No matter the bluster, UK's geo-political obligations to the European Union leave it with little scope to make dramatic alterations to these free policies.

With India however, the deterrents are already, firmly in place. And so, on his third visit, Cameron's hard posturing on holding ‘no limits' to Indian students immigrating to the UK is unlikely to cut ice.

Without doubt, Britain needs to control immigration, especially unskilled labour that proliferates its economy under the grab of seeking an education. But what it is doing now with hugely unfriendly immigration rules is disallowing even the ‘best and brightest' of students that it seeks to attract.

That's a shame because student exchanges have not only contributed hugely to the UK's GDP, but also created immense social capital through alumni networks and budding diasporas. That, is at the threat of being undermined.