| « Back to article | Print this article |

DON'T MISS: Adventures of an intrepid woman driver

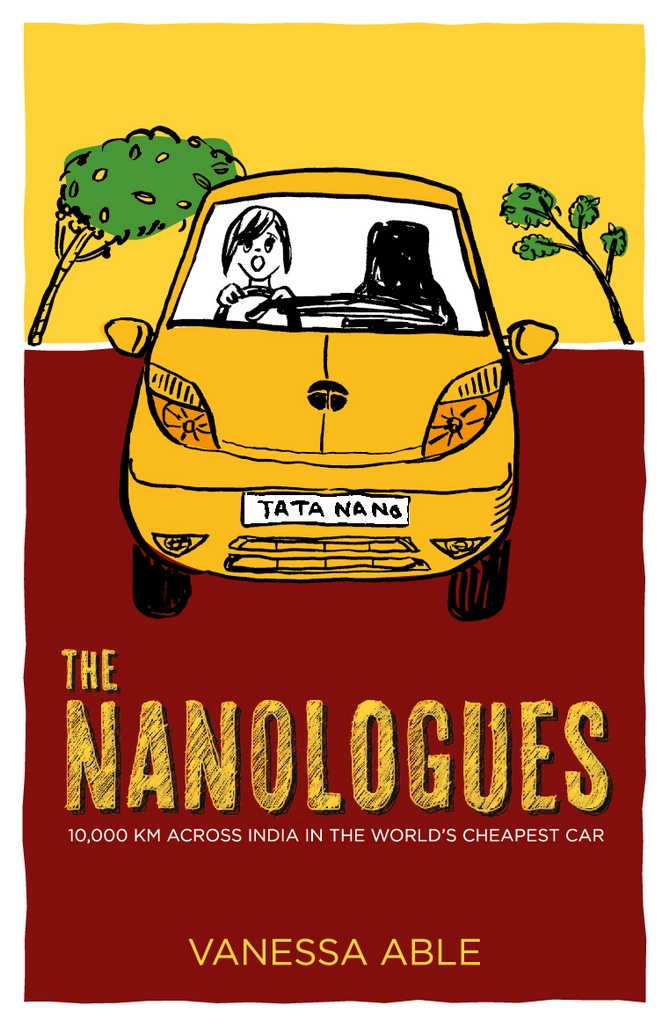

Tata Nano may be the world's cheapest car but can it survive being driven over 10,000 km around the country it was made in?

British writer Vannessa Able decided to put it to test... and write about it! The result was a fascinating book called The Nanologues. An exclusive excerpt:

Travelling across the length and breadth of India, Vanessa Able went to places where no Nano had ever gone before. As GPS systems failed, bullock carts competed for space with SUVs and trucks tried to sandwich her trusty steed, Abhilasha, the name she'd given her trusty lemon-yellow Tata Nano, Able drove on with a single-minded determination.

In the pages to follow, we bring you an excerpt from Vanessa Able's book The Nanologues in which she documents her fascinating journey.

This extract is from her stay in Puducherry, Tamil Nadu:

***

If you're going to be colonized, I mused as I tucked into a ham and cheese pancake while entertaining the idea of an evening of jazz and surrealist poetry at the Alliance Francaise, be colonized by the French. After all, they're the one nation with a God-given knack for bringing the chic into the wilds of the developing world due to their staunch refusal to leave their cultural and culinary foibles at home.

Climate, geography, local economy and distance from Paris have never been factors in discouraging the French from carrying on as though they were in the thick of the Champs-Elysees.

From lobster-and-foiegras-luxury on Caribbean islands like St Barthes and the twee-latticed wooden porches of New Orleans to the flouncy neoclassical flourish of the Opera de Hanoi, there's a tangible thread that runs through the former French colonies that would read something like: 'Well, if we're stuck out in this trou du cul du monde, we might as well make the most of it. Chateauneuf du Pape, anyone?'

Puducherry was governed by the Trieolore until 1954 -- which, history buffs will note, was a good few years after the British left India. Its moulding at the hands of various Franco-Tamil architects over the centuries left a genuinely pretty town replete with churches, cultural centres and big mansions surrounded by courtyards and beautiful walled gardens worthy of filling several issues of World of Interiors.

Compare the cutesy, picturesque, bougainvillea-adorned streets of Puducherry with Lutyens' monumental brick-and-motar fest around Delhi, and you'll get a fair idea of the difference in Franco- and Anglo-colonial styles.

Excerpted from The Nanologues by Vanessa Able with kind permission from Hachette India, (Rs 399)

Purchase a copy of The Nanologues here!

DON'T MISS: Adventures of an intrepid woman driver

More than half a century after the administration packed their Louis Vuittons and left, Puducherry is still fragrant with the essence of Gaul: the gridded streets of the old French Quarter (today referred to rather uncomfortably as White Town, which I had to presume was a reference to the skin colour of its former inhabitants rather than the few remaining whitewashed walls) were named after notable Frenchmen with Indian connections, like author and philosopher Romain Rolland, Admiral Pierre Andre de Suffren de Saint Tropez and Francois Martin, Puducherry's first governor-general.

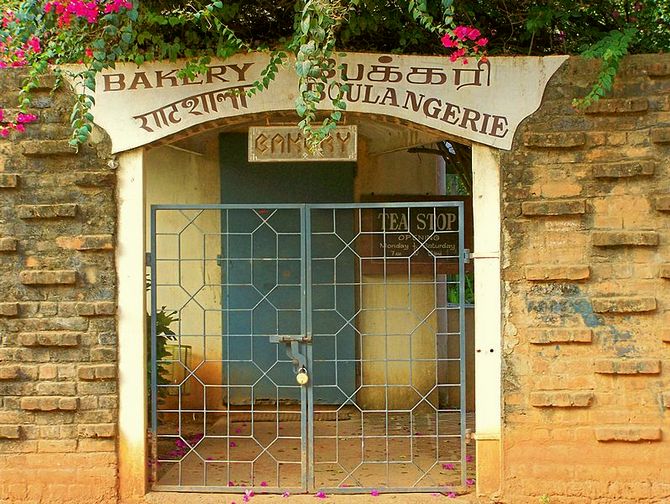

Many former colonial houses had now been converted into fancy hotels, restaurants, cafes and boutiques; menus around town boasted relatively impressive wine lists to go with their steak frites and croque monsieurs, and the boulangerie in Baker Street seemed to be frequently filled with homesick Frenchies munching on croissants and pain au chocolats that were a fair replica of the ones they'd be buying back home.

In addition to the French accent, Puducherry had other merits: it was the kind of town where Christians, Muslims and Hindus appeared to live quite contentedly side by side in their respective quarters; mosques, churches and temples stood within streets of one another and were often subject to varying degrees of stylistic overlap.

Not far from the Alliance Francaise was one bright turquoise building I had presumed was a Hindu temple until its caretaker spied me and pulled me inside for a gander. He asked me hopefully if I was a devotee of St. Anthony before showing me the interior of a hall with a thatched leaf ceiling held up by bamboo poles.

There was a pink altar at one end that contained a small statue of the saint surrounded by flowers and cherubs in a vibrant, cacophonous style that would have been more at home among the colours of Holi than the usual sober decor of a Christian church. I emerged after a lengthy chinwag with the custodian (who was disappointed by my scant knowledge of St. Anthony and all his good deeds) to find Abhilasha relaxing on Suffren Street with the insipid obedience of a well-trained hound at a dog show.

Her jovial, upwardly pointed headlights demonstrated blissful indifference as to what lay outside the phlegmatic streets of the French Quarter, as well as what seemed like a lightly flirtatious bearing directed towards a rather handsome Hyundai that was parked right in front of her, bumper to bumper in an Eskimo kiss. The car was sparkling grey, its bonnet draped with a garland of marigolds and its headlights daubed with large dots of red powder.

I imagined it was these decorative details that had attracted Abhilasha to the dishy vehicle in the first place, though I doubted she knew that, in fact, they were telltale signs that this particular jalopy had come fresh from the car showroom via a Brahmin's benediction.

I had read that when a new car is purchased in India, barely does the ink dry on the registration papers than the owner makes a beeline to the local temple where a priest marks it with a sign of divine insurance.

Even for the non-religious, a car's spiritual servicing is considered as important as checking its brakes and testing its horn; having it blessed before taking it out on the road greatly increases one's chances of not being pulverized under the wheels of an articulated lorry.

DON'T MISS: Adventures of an intrepid woman driver

I had also read about Ayudh Puja and thought it to be an excellent idea. And yet I couldn't help but wonder whether the respect afforded under the sanctimony of a Brahmin was some form of guilty and superstitious compensation for the extreme lack of consideration that seemed to kick in once the car was safely out of the temple and on the roads.

Was it basically okay to drive like a maniac before going into a temple and begging your god for forgiveness for all the heinous traffic sins you just committed? Was this obeisance to one's car in a whirlwind of incense and a sprinkling of powder a bit like wiping clean one's weekly sins at Sunday confession? And did such attention to a car's spiritual wellbeing mean that one was then covered by the ultimate divine insurance company?

Contemplating the flashy garlanded Hyundai that looked like it was trying to get its leg over Abhilasha, I began to wonder whether I had such godly protection. Had Mr Shah of Mumbai thought to have the Nano blessed before selling it on so quickly? And even if he had, did the blessing only apply to the current owner or to the car's future proprietors as well?

The issue seemed laden with complications, and I was beginning to think that Abhilasha and I might be at a disadvantage. How could we possibly compete with all the other cars on the road, the ones with swastikas dangling from the rear-view mirror and little framed pictures of Shiva and Lakshmi next to the ignition? Looking around at the other cars parked on the street, I realized that all of them carried some sort of talismanic trinket, ranging from the religious as far as the political.

My favourite was an arrangement of stickers on the back of a Mahindra Verito that displayed the petition 'Jesus Save Me'. The stencilling was detailed and intricate and looked like it had taken someone the best part of a week to do. Whether it had occurred to them that they had paradoxically also reduced their chances of earthly salvation by almost entirely blocking all visibility from their rear window was another matter.

I decided nothing would be left to chance. Our dashboard-bound three-inch plastic Ganesha did not necessarily guarantee adequate divine protection. I wanted more; I wanted the full Monty. Exactly how to have Abhilasha properly consecrated became the next big question:

Did it matter that my name wasn't on the registration papers? Should I wait until Dussehra? Could a non-Hindu feasibly waltz into a place of worship and demand that her car be blessed?

DON'T MISS: Adventures of an intrepid woman driver

I decided to consult Radhika on the issue, who assured me getting Abhilasha consecrated would not be a problem; she suggested I have the blessing performed right there in Puducherry and immediately dispatched the ever-acquiescent Bagalavan to meet me at the Manakula Vinayagar temple in the centre of town.

Particularly appropriate in that it was dedicated to none other than Ganesha himself, the temple came complete with its very own elephant, who went by the name of Lakshmi, and who stood obediently outside the main entrance. Lakshmi's main job appeared to be taking coins and bananas from faithful devotees and trepidatious tourists and in return imparting darshan, a blessing, in the form of a light pat on the head that made most recipients quiver and screech.

Following Abhilasha's recent manhandling on our way from Kanyakumari to Madurai, 1 was very wary of the lumbering, runny-nosed proboscidea. However, Lakshmi appeared to be a different class of elephant altogether: elegant, polite and decked out in some rather attractive ankle bracelets. She seemed quite happy to dole out blessings to anyone who'd toss her a prize, and 1 eventually succumbed to her charms and flipped a ten-rupee coin towards her. 1 figured garnering a bit of goodwill with a real-life Ganesha could only further my cause of maximizing favour with the gods.

No sooner had Lakshmi patted me on the head (I was relieved to see her trunk was well-blown), Bagalavan pulled up on a TVS Apache bike clad in a perfectly pressed white shirt and jeans. He was bright-faced and business-like, and wasted no time in rushing me towards a kiosk inside the temple where he pushed some rupees over the counter in exchange for a couple of flimsy tickets. We took these around the corner where a Brahmin appeared, ready with his assortment of materials for the ceremony. Wearing a lungi and a thread looped diagonally across his bare chest and over his shoulder, he was balancing four limes and a pot of deep red sindoor on an aluminium tray with a burning oil lamp soldered onto the end of it.

Bagalavan disappeared somewhere and I was left grinning at the Brahmin over the smoke of his oil burner. I pointed towards Abhilasha and his expression became grave as he nodded his head in a gesture of acknowledgement. Bagalavan returned with a garland of marigolds, which we hung from Abhilasha's rear-view mirror, as well as a line of jasmine for my own hair.

And so the ceremony began: the Brahmin started by standing in front of Abhilasha's bonnet and applying dots of sin door on her headlights, number plate and on a spot on the windscreen that fell roughly where her forehead should be. Then he circulated his burning oil lamp around to the driver's door, where he got in (my maternal gut clenched at the sight of an uncovered smoking oil lamp thrust deep inside Abhilasha's delicate and presumably flammable interior) and proceeded to dab bits of sindoor powder around the steering wheel and dashboard.

He then placed a lime underneath the front and back tyres before moving around to her posterior, where he applied more sindoor dots to her rear lights and number plate. The remaining limes were duly placed under Abhilasha's left tyres and all that was left was for me, my own forehead now also sindoored, to get in and slowly drive forward, thus making limeade with Abhilasha's treads.

As quickly as it started, it was over. Abhilasha, smoky and powdered, had now officially been blessed and sanctified. As far as the gods were concerned, she was all right and well worth keeping a divine eye on. Ganesha beamed up at me from the dashboard as the Brahmin hovered by my open window.

'Ma'am, you must give him a little baksheesh,' Bagalavan informed me from over the holy man's shoulder. I gave him a 50-rupee note and he went on his way.

'So is that it?' I asked Bagalavan, incredulous that this all-important act of karmic insurance had been so fleeting, simple and, er, cheap. 'Yes, ma'am. That is all. Now you are safe to drive and you will be protected from all accidents.'

DON'T MISS: Adventures of an intrepid woman driver

Excellent, I thought. Pricey insurance policies be damned, I now had a much more powerful source of indemnity on my side. I thanked Bagalavan -- who seemed eager to be dismissed as I guessed Radhika had piled him high with jobs for the day -- and set off with Abhilasha for a celebratory croissant.

Later that day, I was taking Abhilasha through the narrow lanes of Puducherry's Muslim quarter looking for the front porch of the man with whom I had left a bundle of my washing hours earlier. As we rounded a corner I had a strange rush of uncoordination and took the turn too tight. The laundry man's ironing table hovered into view as I felt an almighty scrape on the right-hand side of the car. I stopped dead and felt the stomach-churning wince of recognition as I turned to see that I had rubbed Abhilasha against a concrete lamppost; a bit like how a cat would rub up against your leg, only to the teeth-clenching sound of grazed metal.

'S**t. S**t, S**t, S**t!'

The laundry man stood on his porch watching me with the curious inertia of a doctor sloth.

'S**t!' What to do now? I figured that if I kept moving forward, I would inevitably draw out the scratch even further. Going backwards seemed a much more sensible option, so I put Abhilasha in reverse and tried to extricate her from her concrete clinch.

Another hideous rasping noise. It seemed that my attempts at retracting my imbecilic action had piled stupidity on foolishness. We were back where we started, except that Abhilasha now had two enormous scrapes along her right rear haunch.

I looked down at Ganesha who was as indifferent as the laundry man.

He gave me no clues where to go next. I was shattered: why had this happened? Weren't we supposed to be protected? Irony didn't begin to encapsulate what had just occurred. The heat-withered marigolds still hung from the rear-view mirror, the sindoor continued to cling to the steering wheel and bits of lime were still freshly wedged between the rubber grooves of Abhilasha's tyres: here we were, four hours after our blessing (our 50-blimmin-rupee blessing, I inwardly snapped) and we were in the midst of our first accident of the whole trip.

And what an accident. This was not one to rile audiences with; it was hardly the stuff Hollywood car crashes were made of. There had been no errant rickshaws crossing my path; no buses swerving ferociously into my lane; no drunken lorry drivers falling asleep at the wheel and taking the Nano head on. It was a bright and sunny day, I had been driving on an empty road at 10 kmph, and the only extenuating factor in the entire incident was my own stupidity. I had scraped the lamppost with all the composure and grace of a pissed vagrant falling against a wall. And then I had reversed for more. The laundry guy was still staring at me. He hadn't moved a muscle. I mentally willed him to get back to his ironing as his proximity to the accident and the fact that he was the sole human witness of my injudicious manoeuvre put him first in line for unfair retribution.

I swung Abhilasha's wheel hard to the left and managed with only a small additional scrape to free her from the lamppost's clutches.

I pulled her up outside the laundry man's porch and got out to inspect the damage. It was as bad as I imagined: there was a series of thin wavy lines stretching from Abhilasha's taillight all the way to the hinge of the passenger door that had scraped away the paintwork and exposed the grey metal underneath.

'S**t it!'

I turned to face the laundry man, who continued in his wordless contemplation of the scene. I put my best anger management skills into action as every ounce of my being was channelled into the act of politely asking him for my washing back, and not for the chance to furnish him with a knuckle sandwich. He reached for a pile of familiar folded clothes that had been placed on a stack of newspapers behind his ironing table. He then quoted a price that was Rs30 more than I had previously agreed to with his wife that morning. My blood pressure rose to mass-murder levels, and the man seemed to instantly recognize the killer instinct in my eyes. I handed over the agreed price and he accepted without a word. Without looking twice at Abhilasha's mangled haunch, I got back in the driver's seat, ripped the marigolds from the mirror and sped away from the laundry-wallah's house.

***

Excerpted from The Nanologues by Vanessa Able with kind permission from Hachette India, (Rs 399)

Purchase a copy of The Nanologues here!