For podcasters -- those who create podcasts -- the medium's appeal also owes to the fact that its content remains unregulated.

Uncomfortable conversations, taboo subjects, stigmatised issues, are all encouraged.

Amrita Singh reports.

Freshly washed and as blue as the sky after a much-awaited shower, a house in Chittaranjan Park in south Delhi serves partly as a studio that goes by the name Studio Logicbox.

Its walls are lined with red and blue foam, or, as geeks would say, more precisely, Mass Loaded Vinyl (MLV) soundproofing foam.

Adjacent to the control room, which is fitted with four iMacs, is the recording room where Deepti Ahuja, an independent podcaster, is working on an episode for Delhi-based podcast platform, Hubhopper.

Her podcast, Kachi Mitti, of stories with a message, is a Hubhopper original with six episodes. Hubhopper has an expanding catalogue of over one million hours of content.

Podcasts -- a portmanteau of 'iPod' and 'broadcast' coined by British journalist Ben Hammersley -- gained popularity in the West around 2004.

In India, these audio files that can be streamed or downloaded over the Internet are only beginning to find a following.

Besides podcast apps such as Hubhopper, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, music streaming apps like Saavn, Gaana and Spotify have also started making podcasts available.

It all really started with Indus Vox Media. Amit Doshi, the founder of Mumbai-based IVM Podcasts, had grown up listening to podcasts in the US.

Some five years ago, the 45-year-old entrepreneur began toying with the idea of introducing a platform for podcasts in India as well.

It was, after all, a relatively unexplored market. With co-founder Kavita Rajwade, an industry veteran of 15 years who has worked with organisations such as Sony Music, Doshi started IVM in 2015.

Both Rajwade and Doshi also felt that the country needed a fresh new avenue for informative, sometimes funny, but always noteworthy, content.

IVM's first show, Cyrus Says, came out in 2016 with Cyrus Broacha's satirical take on anything and everything -- politics, sport, traffic, even kids. "We wanted someone popular, someone who could keep our audience engaged," says Doshi.

IVM's podcasts target the 18 to 50 age group. And Broacha, a well-known personality with a recognisable voice and an ability to connect with diverse people, was an instant hit.

A series with more than 400 podcasts in its kitty, Cyrus Says continues to be one of IVM's most popular shows, with a five-star rating on Apple Podcasts.

Since they are still finding their feet, several Indian podcast platforms share their content with other such platforms, while retaining exclusive rights to some of the shows.

Besides IVM and Apple Podcasts, Cyrus Says, for example, can also be streamed on Google Podcasts and Headfone.

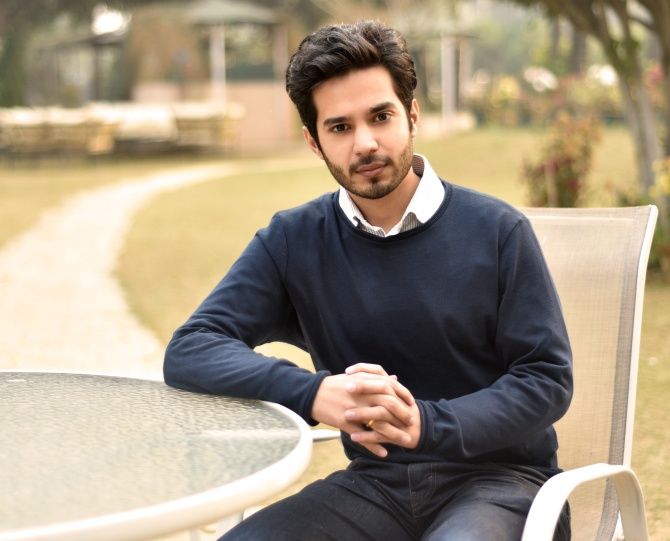

Padma Priya, founder-editor, Suno India. Photograph: Kind courtesy Suno India

For podcasters -- those who create podcasts -- the medium's appeal also owes to the fact that its content remains unregulated.

Uncomfortable conversations, taboo subjects, stigmatised issues, are all encouraged. "We have a show called Dear Pari, the sole purpose of which is to create awareness about adoption to destigmatise it," says Padma Priya, founder-editor of Suno India, a podcast platform that addresses social issues.

Similarly, Mumbai-based gynaecologist Munjaal Kapadia talks about sex, contraception and motherhood on his podcast, She Says She's Fine. His podcast on miscarriage, he says, was a big hit precisely because most people tend to avoid conversations on the subject.

Podcasts are in many ways filling the gap that radio failed to because, in India, radio content is highly regulated.

A 2012 advisory to radio channels by the information and broadcasting ministry disallows 'criticism of friendly countries, anything obscene or defamatory, attack on a political party by name, hostile criticism of any state or the Centre and anything amounting to contempt of court'.

Podcasts are free of such constraints.

"Also, did you know that Mumbai has 11 radio stations whereas New York has 140?" asks Doshi in exasperation.

A 10-year licence for radio broadcasting costs about Rs 150 crore (Rs 1.5 billion) in Mumbai and Rs 180 crore (Rs 1.8 billion) in Delhi, he says.

It's also a capital-intensive venture. Producing a podcast only requires a portable recorder, a good mic and some editing software, which makes entering the podcast industry relatively easy and inexpensive.

When Mae Mariyam Thomas, a former radio news journalist, returned to Mumbai from Wales in 2010, she wanted to continue with radio.

After working with multiple radio stations, including 94.3 Radio One, she quit in 2014. "I felt jaded. I loved the medium, but there wasn't any diversity in content because you can't really cover news on the radio here," she says.

So she moved to music. Her show, Maed in India, which started on IVM in 2015, was the country's first indie music podcast.

Her studio in Khar, north west Mumbai, has since hosted aspiring bands and singers as also established names like indie musician Prateek Kuhad. Her podcasts, recorded in a "60 per cent music, 40 per cent talk" format, feature her having candid conversations with musicians about their life and work.

For many indie artistes, Thomas's show is a means of reaching out to a larger audience, sometimes even playing for them for the first time.

Her podcast became so popular that last year Maed in India went independent and is now available on almost every podcast-streaming platform. It was part of Apple's list of Top Eight Indian podcasts for 2018.

The podcast ecosystem is unique in that a listener can easily become a creator of content. Hubhopper capitalises on this by offering an online 'recording studio'.

You can simply record and upload your podcast on Hubhopper without having to go to a brick-and-mortar studio, though the sound quality might not be as good.

"People want to be heard," says Gautam Raj Anand, founder, Hubhopper. "You can make your podcast ready for online publishing within two minutes on our online studio," he says.

Anand began listening to podcasts when he was working at Barclays. Within months he was listening to 12 to 14 hours of content every day.

His stressful job, he says, led him to "sleep to a podcast playing in the background". Eventually, he quit his job to develop Hubhopper, which today has over 400 podcasters. Quantifying the number of listeners, however, remains a challenge given the nature of the medium.

According to Anand, most people spend five hours of screen time a day on their phones, mostly on Facebook, YouTube, Instagram and WhatsApp. Hubhopper is not vying for those five hours.

"Podcasts are meant for off-screen consumption, which means that the content moves with you. You can tune in and tune out whenever you want, and multitask," explains Anand. Like when you are listening to the radio.

Angana Chakrabarti, a journalist, and Manan Bhan, an ecologist, both use their long commutes to listen to podcasts. Chakrabarti also tunes in while getting ready for work. "I think I've become more patient since I started listening to podcasts," says Bhan.

Since podcast platforms in India offer content for free, the funds to sustain them usually come through advertisements and brand sponsorships. Brands are beginning to realise that this medium is ideal for targeted advertising.

A podcast on start-ups, for example, will be heard by entrepreneurs, making it easier to zoom in on what might be of interest to these listeners.

Most ads are played in a dedicated ad slot, but sometimes they seep into the content, and users don't seem to mind that. "Because it's a trusted voice, it works," says Bhan.

Storytel India, a platform for audiobooks and e-books in English, Hindi and Marathi, chooses to advertise with IVM Podcasts as both these platforms have the same audience.

"Those who listen to podcasts are essentially the ones listening to audiobooks as well," says Yogesh Dashrath, country manager for Storytel India.

"We tried advertising with IVM for the first time last year and the results were great. We plan to continue advertising with them."

To stream a podcast, you need a smartphone and specific applications that can be downloaded (unless you're an iPhone user, in which case the podcast application comes as an inbuilt feature).

English language podcasts are more commonly heard than those in other Indian languages. But this is slowly changing.

Naveen Haldorai hosts a history podcast called Varalaru in Tamil on his channel, Curry Podcasts. It examines Indian history through real stories and narratives.

Similarly, Hubhopper has podcasts in 15 Indian languages and Suno India in four. Suno India, a platform for reported stories, was launched by two journalists in 2016. It creates narratives on various issues -- from climate change to the necessity to vote.

The world of podcasts has something for everyone, whether it is news, politics, comedy, technology, arts, culture or fiction.

Want to tune into the BBC World Service? Or listen to Jaggi Vasudev? You can do both on the same platform.

Hubhopper's data indicates that most people listen to inspirational talks on their way to work, and lighter stuff, such as comedy shows or music, on their way back.

Podcasts might be relatively new to India, but the concept is not. For a generation used to 'plug-and-play', commuting to work with a placenta-like feed to the ears, the smartphone has opened up a whole new world.

Podcasts are only expanding that fascinating universe.

© 2025

© 2025