Siddharth Tata's Purple Chilli helps vegetable farmers earn an income 365 days a year.

When Siddharth Tata graduated from the Indian Institute of Technology-Madras -- living up to Indian middle class expectations -- he had no intention of pursuing his life-long love for business.

But as it always does, life happened.

His job at work at McKinsey & Company opened up a whole new world of rural India for him, and there was no going back.

Siddhart tells Rediff.com's Shobha Warrier about the road less travelled.

A unique professor at IIT-Madras

I had a very normal middle class life as a child in places like Chennai, Delhi, Kochi, etc. My father, who worked in public and private sector banks, had a transferrable job.

Though my grandfather and some of my uncles were entrepreneurs, like in all middle-class families, I was expected to study well and study engineering, preferably in an IIT.

I looked up to my elder brother Sandeep and always wanted to do what he did. In school, I used to read business and economic dailies a lot, and dream of starting something of my own, but when he got admission at IIT-Madras, I also wanted to study in the same institution. I did too.

Though I studied electrical engineering, I continued to have an interest in business and commerce. But I had no plan to pursue it.

At IIT-Madras, I was inspired by what Professor Ashok Jhunjhunwala was doing, especially the Incubation Cell he had started.

What he was doing was unique and so much more than what a government college professor was expected to do.

The work he did using engineering and technology for the development of society definitely prepared us for what we wanted to do after our studies.

Working with the Gates Foundation

After my studies, I worked with McKinsey for four years. It was here that I got a chance to do consulting work in the rural and agricultural sector for a year.

This was a complete eye opener. The visits to poultry projects in Orissa and Madhya Pradesh and dairy projects in Pune were something I had not experienced before.

My work in rural areas while working for McKinsey made me look for more work in the rural area.

That was how I got a chance to work with the Gates Foundation as a part of their agriculture development team.

My role was to locate, evaluate and recommend non-profit projects to the foundation so that they could fund those that were doing good work in agriculture.

After my visits to the rural areas I felt there were so many problems that technology could solve, and it was for us -- those who know technology -- to create solutions to the problems.

The question was: How do you apply technology, engineering, business and trade management principles to solve the problems a vast majority of people face?

Technology is very important, but at the same time, you need qualified people to find solutions using technology.

Technology can be used to even overcome the unpredictability that is in the agricultural sector.

The challenges are quite unique to this sector, which you don't see in the corporate sector; this was what attracted me to the sector.

Off to HBS

I worked with the Gates Foundation for a year and then decided to go to the Harvard Business School.

It was to equip myself better that I went to Harvard, and I clearly stated it when I applied.

I was sure I would come back and work in the agri business.

I wanted to get a broader perspective of the sector as my knowledge was more India focused.

At Harvard, I could study about the dairy industry in China, the grain industry in Brazil, etc, which turned out to be extremely useful.

The two years definitely helped me learn more on what I have been doing after my studies. Those were two very well invested years.

On to Acumen Fund

After I came back to India in 2010, I felt I was not ready to be an entrepreneur yet.

Though I spent a lot of time studying entrepreneurial ventures in the dairy sector, I chose to work for Acumen Fund as head of the agricultural portfolio.

It was like, if you cannot be an entrepreneur, you can at least work with the entrepreneurs who are early in their journey and help them become successful.

Working in education, agriculture and affordable housing, one of the biggest lessons was striking the right balance between development work and running a business.

I saw many enterprises fail because they could not strike a balance.

I was also working directly with farmers and it helped me understand why they take certain decisions and how they respond to innovations.

For example, it is well known that micro irrigation is very useful for yield, saving water, preserving soil, etc, but it was interesting to find out why farmers had not embraced it wholeheartedly even though it is not that expensive.

The question I had was: Why do innovations not always succeed? This was one question I asked all the farmers I met.

I came to the conclusion that it was a combination of issues -- there was a gap in what was promised by the innovator and what was actually needed by the user, there was the problem of affordability and availability of the product.

Finally, an entrepreneur

In May 2015, I felt I was ready to be an entrepreneur.

I knew entrepreneurship is all consuming, and I had to be fully ready to plunge into it.

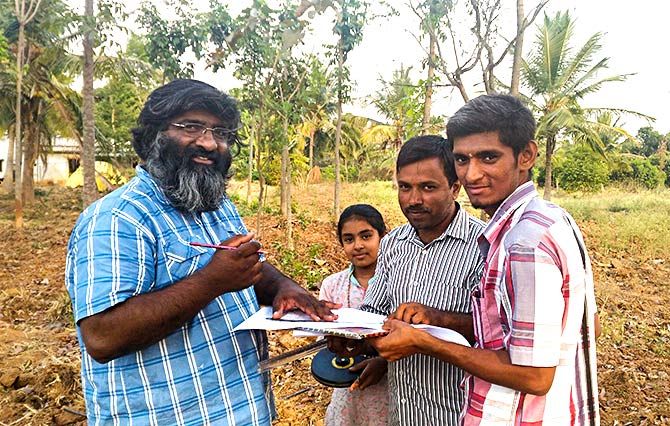

In 2016, I joined hands with Shashi Kumar, who was an experienced entrepreneur in agriculture having been involved in many successful ventures in the past.

He chucked his job as an IT professional to be an organic farmer and lives in a village. He has been growing his own food for quite a few years.

We started Purple Chilli with our own finance and seven members.

With their methods, a farmer can have a stable income of ₹15,000 to ₹20,000 every month from one acre of vegetable cultivation.

Why Purple Chilli?

Our notion of chilli is green or red, but Shashi has 25 varieties of chillies in his farm and the purple chilli was his favourite one as it is very unique in the way it grows.

All chillies grow with the tip facing the ground, but purple chillies grow with its tip facing the sky.

Locally, it is called Gagan Mukhi. We decided to name our venture Purple Chilli to demonstrate the diversity of food we have.

The risks of being a vegetable farmer

Though I had done a lot of work in the dairy field, I felt cultivating vegetables posed the biggest problem for a farmer.

Situations arise when farmers have to sell onions, tomato, potato, etc for 50 paisa or ₹1.

Such situations are very common. I have seen fields full of tomatoes left unattended as the farmers were not even ready to harvest them.

The price was so low that they felt it a waste of time, money and energy to harvest.

You also see the other side of the coin when prices skyrocket.

As far as vegetable cultivation is concerned, there is unpredictability all the time.

The other day we were sitting at a mandi and at 5 am, tomato price was ₹15, but by 7 am, it fell to ₹8!

This is a reality every farmer who is growing vegetables has to face.

It is very risky to be a vegetable farmer.

It is to solve the unpredictable vegetable market which farmers face that we decided to start our venture.

The basic principle behind Purple Chilli is if something is very risky, you diversify so that your risk reduces.

For four to five months, Shashi and I talked about what we were going to adopt before deciding on the right model: That a farmer with an acre of land not grow just one vegetable, but around 20 to 25 varieties of vegetables simultaneously and 365 days a year.

For example, when a farmer plants onion, he waits for 90, 95 days, harvests them and then takes them to the market. So, he has a harvest in three to three-and-a-half months.

Instead, we help the farmer plant 20, 25 varieties of vegetables in a very carefully planned manner so that he is able to harvest every day.

The idea behind this kind of farming is it helps him have an income every day throughout the year.

How Purple Chilli works

We first invested in a farm as a demonstration piece to show farmers how our model works. We prepared the soil, had drip irrigation, back up power, bought seeds, etc.

We want to tell farmers that there is a capital investment of ₹2 lakhs to ₹4 lakhs (₹ 200,000 to ₹400,000) involved initially for an acre of land, but he will start getting continuous income after three to three-and-a-half months, that is, once the harvest starts.

Yes, it was quite difficult to convince the farmers of the concept first.

Somehow, we could convince a farmer called Sadasiva. It was in Ramanagaram district outside Bengaluru.

After we developed his farm, around 500 farmers in the neighbourhood started visiting him and enquiring about how he goes about it.

Ten farmers have joined the initiative now and we have 10 acres to develop as vegetable farms. We also developed four farms in different configurations for Sadasiva.

This kind of farming requires constant monitoring. Our staff members assist the farmers in case they have any problem.

Soil preparation is very important because the nutrient demand of each vegetable is different.

So, we first check the technical feasibility of the soil, water availability and then have a long chat with the farmer to see whether he is ready to do something different.

Then, we have to decide what combination of vegetables should be put together so that you get the best out of the limited land.

Plants compete with roots and foliage and keeping this in mind, we have to design the farm. For example, beetroot and amaranthus are a good combination.

Since this kind of farming has harvesting every day, it also requires planting every day. We supply all the necessary seeds to him.

Though we help the farmer in soil preparation, drip irrigation and seed procurement, the day-to-day farming is done by him.

We also procure the produce from the farmer and sell it in the market.

We take care of procuring of seeds and marketing the produce because we want the farmer to focus completely on the production and not marketing his produce because the most important worry of a vegetable farmer is the price and the market.

As we procure his produce, he can have a stable income of ₹15,000 to ₹20,000 every month from one acre of vegetable cultivation.

To market the produce, Purple Chilli has developed a direct-to-customer organic vegetable subscription, which we are doing in Bengaluru.

Our revenue model is only by selling the vegetables as we do not charge anything from the farmer; that is not the idea behind Purple Chilli.

It has been very exciting to be a part of something you believe in.

It is rewarding when the farmers tell you that what you do has made some difference in their lives and when customers in the city write to you saying the greens and vegetables we supply are the best they ever had.

Don't miss: How Young India is changing agriculture

- 4,000 farmers owe their livelihoods to her

- A software engineer who quit his is making farmers richer

- She is going to grow vegetables after a PhD

- From networking to farming

- He left a Rs 90K-job to work with farmers

MORE ACHIEVERS in the RELATED LINKS BELOW!

© 2025

© 2025