HNI investors need an optimal mix of oversubscription and listing-day gain to make money on leveraged bets, notes Sanjay Kumar Singh.

There have been 54 mainboard initial public offerings (IPOs) so far in 2021, of which 30 have gained 10 per cent or more on listing day.

The rest have delivered either single-digit gains or made losses on debut.

The level of subscription has ranged from 0.15 to 150 times.

This variation in outcomes makes IPO investing using borrowed funds a risky proposition for high networth individuals (HNIs).

Short-term loan

The interest cost for IPO funding ranges from 10-14 per cent.

This loan is generally taken for seven-eight days.

The margin requirement (amount the investor pays out of his pocket) can vary from 1 per cent to 15 per cent.

Where the oversubscription is expected to be higher, the margin demanded is less, and vice versa.

Leveraging to magnify gains

HNIs borrow money for three reasons when applying for IPOs.

One, leverage can magnify gains. Two, since issues tend to get heavily oversubscribed in bullish conditions, borrowing allows them to apply for a higher amount, which improves their chances of being allotted more shares.

And three, as Rahul Shah, senior vice-president, private client group, broking and distribution, Motilal Oswal Financial Services, says: "With the IPO process from application to listing getting reduced to a week (from a month earlier), HNIs feel more confident about being able to predict the outcome."

Myriad risks

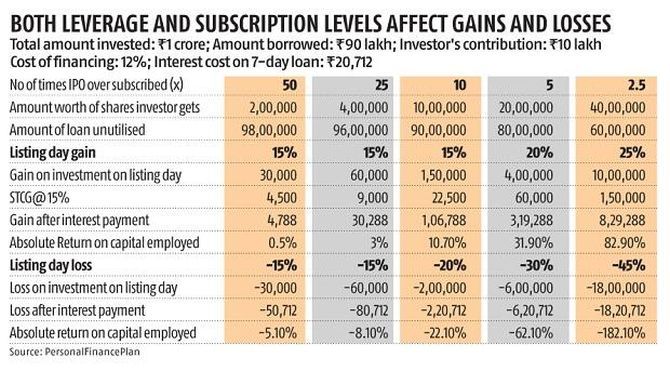

Several factors determine whether a HNI makes a profit or loss on a leveraged bet.

One is the level of oversubscription. If the IPO is sought after, oversubscription is higher.

If oversubscription is x, the HNI is allotted shares worth 1/x the amount he applied for.

Lower allotment means he has fewer shares whose listing gains he can enjoy.

Oversubscription also affects the HNI's cost of funding per share.

"The investor has borrowed a certain amount. Now, if the level of oversubscription is higher, he gets fewer shares, so his per share cost of funding increases," says Roop Bhootra, chief executive officer, investment services, Anand Rathi Shares and Stock Brokers.

When an HNI uses the leveraged route, his total cost per share becomes the sum of the IPO price plus his funding cost per share.

Oversubscription pushes his breakeven point higher.

The second key factor is the quantum of listing gain.

If the pricing of the IPO is exorbitant, the probability of gains declines.

"Typically, promoters and investment bankers price IPOs expensively in bull markets and leave very little on the table for investors," says Ankur Kapur, managing partner, Plutus Capital, a Sebi-registered investment advisory firm.

Market sentiments can change quickly.

"Many HNIs pull their applications on the third day if they anticipate a loss," says Shah.

Those who are not tuned in go ahead with them.

They get a higher level of allotment, which pushes down their funding cost.

But if the anticipated listing gains don't materialise, they end up making a loss.

Experts cite the example of the SBI Cards IPO.

It had sound fundamentals and was expected to deliver good listing gains and do well in the long run.

However, at the time of its IPO, the pandemic hit and caused market sentiment to sour. Instead of gains, there were listing-day losses.

HNI investors need an optimal mix of oversubscription and listing-day gain to make money on leveraged bets.

Remember, leveraging magnifies losses. If there are losses on listing day, the investor has to shell out not just the interest cost, but also the capital loss on the entire leveraged purchase.

What can you do?

Before making a leveraged bet, study the company's fundamentals.

"Also evaluate whether the IPO is reasonably priced in relation to its fundamentals," says Bhootra.

Sound fundamentals improve the likelihood of good demand for a company's shares and, hence, the chances of listing gains.

Shah says that even in the worst-case scenario, if you don't make listing gains, but the shares you are stuck with are of high quality, you will be able to exit at a profit when their price eventually recovers.

On the other hand, prices of poor-quality shares may never recover and rise past your break-even point.

Feature Presentation: Aslam Hunani/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025