| « Back to article | Print this article |

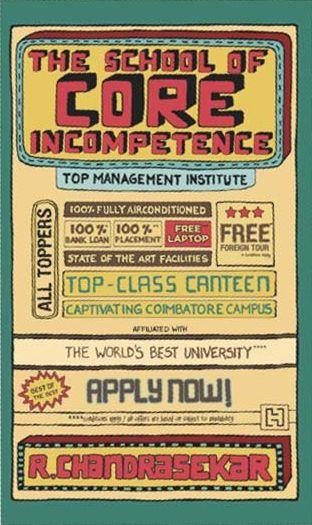

We bring you an excerpt from R Chandrasekar's new book, The School of Core Incompetence.

We bring you an excerpt from R Chandrasekar's new book, The School of Core Incompetence.

With a background in finance and education, Chennai-based R Chandrasekar turned author with the novel The Goat, the Sofa and Mr Swami, which received a hugely positive response.

His second, The School of Core Incompetence -- which paints a hilarious picture of Indian b-schools and the government's mismanagement of education, with dubious degrees and absurd honorary doctorates -- has just been published.

We bring you an excerpt from the chapter Human Resource Management I:

'Professor Agarwal, how can I meet the director with these minutes?'

'Arre, Sambandham sahib, you have the full backing of the committee. The resolution is a unanimous one, no less, and we are all standing behind it 100 per cent.'

Which, Sambandham thought, was precisely the problem.

He hadn't slept for three nights. He had snapped at his wife and had been snapped back at in return. The to and fro had continued with unrelenting ferocity with his beloved daughter taking her mother's side.

If he told the director that he had not been party to the decision, he would have his colleagues stacked up against him with the minutes to back them up. And if he went along with the fiction that the recommendations were unanimous, an episode of extreme unpleasantness vis-a-vis the director was a near certainty. Taking sick leave was out of the question given the situation at home. Distraught, he had bungled his way through two classes, and even in his state could sense that those old standbys, the Kurukshetra-Panipat gang, were also turning against him.

Approaching Agarwal was an act of desperation. He knew that his fellow Tamilians were too caught up in their internecine quarrels to be of help. Like them, he loathed North Indians. But Agarwal was a shrewd fellow and the one most likely to come up with something constructive. Even so, he had never expected this from Agarwal: stonewalling with the blandest of expressions. Damned bania.

'Professor Agarwal, I know I have the full backing of the committee. You yourself have pointed this out. So why shouldn't the full committee meet the director and jointly explain the position? That way the director can see for himself how unanimous we are.'

'Sambandhamji, it is looking to me like you are afraid to see the director.'

'No, no, no, no. Not at all,' Sambandham spluttered.

'Furthermore, it is looking to me like there must be a good reason why the director has entrusted you with the chairmanship of this important committee. With chairmanship comes great responsibility which the director has entrusted in your good self. Who better than the chairman to explain the thinking behind the unanimous resolution? You yourself tell me.'

In his distress Sambandham took off his glasses and wiped them on his shirt. Putting them back on he looked at Agarwal through smudged fingerprints, aware that he looked like a caricature of an absent-minded professor. The unfairness of it all overwhelmed him. He was a helpless figure surrounded by malevolent forces intent on humiliating him. All those years of toil, the toe-hold by toe-hold scrabble up a slippery and treacherous career path, had led him to this, a humiliating end to his career. A deluge of emotions overwhelmed him. He burst into tears.

'Sambandhamji, Sambandhamji, why are you crying?' Dealing with an adult male in full emotional spate was not something Agarwal had had to do in his many years as an academic. Yes, there had been failures to pass examinations, failed love affairs, deaths, and the like, but those were ritual occasions with known scripts. Why was this man behaving like this? Was it something Agarwal had said? Was he supposed to console his colleague? These Madrasis were prone to extreme over-reactions and he was wary of what might happen if he patted Sambandham's shoulder or did something equally innocuous.

He fidgeted nervously, interjecting an occasional 'professorji, professorji', as he waited for this human train wreck to run its course and hopefully reach a salvageable destination. Which it eventually did, with an assortment of sniffles, suppressed sobs and a few involuntary snorts.

Embarrassed now, in addition to being emotionally overwhelmed, Sambandham got up to leave. News of his humiliation would be hitting the airwaves soon and the only thing left for him to do was to put in his papers, pack his bags and try to resurrect what he could of his career elsewhere.

'I'm sorry, Professor Agarwal,' Sambandham said in a muffled monotone, 'I have been wasting your time. Now I shall go.'

Agarwal jumped up. He couldn't let this man go out in this state. News that a card-carrying Tamilian had been seen exiting a North Indian's office in tears would only mean trouble for him. Visions of Thilaka and Anbuchezian at their loudest, and the likelihood that they would be joined by others with a sense of grievance and time to spare, led to Sambandham being manhandled back into his chair, given a handkerchief and a glass of water and cooed over with as much sympathy as Agarwal could muster.

The sniffling stopped and Sambandham blew his nose loudly into Agarwal's handkerchief. Agarwal swallowed hard and said nothing.

'Thank you, professor. Sorry once more. Very difficult situation I find myself in. Most difficult. Now I shall be going.'

'Arre, why are you going? Where might you be going? Sit here. I shall order tea, then we can discuss these matters.'

'I am not going to that bloody canteen.' Sambandham found his normal voice. 'They don't clean tables, they have no respect for senior faculty like me, and on top of everything AICTE discovers rats. I am asking you this: Is it any surprise that two rats are being discovered when tables are not being cleaned and respect is not being given? Green committee recommendations have been accepted in toto and we, our committee, has to find an AICTE-approved rat catcher. Tell me, Professor Agarwal, is this fair?'

'You are absolutely right, Sambandhamji. Absolutely unfair, situation is. Hundred per cent agreed. We shall discuss further steps. But cup of tea first, if I may.'

'I told you I am not going to that bloody canteen.'

'No need to go. I shall ask for tea here.'

'They bring tea to your room? You know, I asked that stupid canteen supervisor once for tea in my room and he said it was against employee union rules. He said there would be a dharna by canteen employees followed by work to rule and then an indefinite strike if faculty wanted tea in their room. You want tea, you go to canteen at specified times -- those were his very words.'

'Sambandhamji, some little advice. These are all situations to be managed. We are in a management institute; we have to manage the situation, that is my motto. Practical management, I call it. You know that boy in the kitchen? I give him ten rupees a month and I get tea-coffee in my room. Practical solution. No rats, no dirty table, no problems. So, tea?'

Stunned by this casual run around the rules, Sambandham could only nod.

The tea was duly served and sipped, Sambandham noting in passing that it bore little resemblance to the stuff dished out in the rat-infested canteen.

'Sambandhamji, action must be taken.'

Fortified by good tea, and rid of excess emotions, Sambandham felt emboldened. 'Collective action only, Professor Agarwal. It is a collective problem.'

'United we stand, divided we fall.'

'Yes, that is my opinion also. What are your suggestions?'

'Immediate problem: rats in canteen. Two numbers as noted already, perhaps even more. Health problem.'

'Health is wealth, Professor Agarwal.'

'Indeed it is. And we are training our students in the making and management of wealth. Without health, what wealth is there to manage? So, first and foremost, a collective protest against canteen conditions is needed.'

'Yes.'

'The next issue is that our committee under your esteemed chairmanship has been given the task of getting rid of the aforementioned rats. Now, I ask you, were we responsible for the presence of the rats in the first place?'

'Of course not. That green committee...'

'Indeed. A problem not made by us. So we shall have a secondary protest wherein we shall discuss with our committee colleagues and request the director to direct those who created the problem to resolve it.'

They sipped tea. Agarwal was relieved at having been able to reach common ground with his colleague, relieved too that the emotional minefield had been traversed. Sambandham was relieved that he would not have to face the director alone.

Excerpted from The School of Core Incompetence by R Chandrasekar, with the permission of publishers Hachette India.