When the universe is your workspace, the sky is the limit, and there's no such thing as a glass ceiling.

Divia Thani Daswani meets the women behind Mangalyaan, India's Mars Orbiter Mission.

What does it take to make sure your little girl grows up to be a rocket scientist?

Start her young.

Some 30 years ago, Ritu Karidhal was a little girl, looking up at the stars twinkling in the Lucknow sky, and wondering why the moon changed its shape and size every night.

In her teens, she began following the activities of the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) in the newspapers, cutting and collecting clippings.

Around the same time, Moumita Dutta was reading about India's first lunar probe, Chandrayaan 1, in the Anandabazar Patrika in her hometown of Kolkata, and thinking 'How lucky those people are to have the opportunity to be part of this.'

Flash forward to 2015, and both women are top ISRO scientists, part of a team that worked on India's acclaimed Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM), aka Mangalyaan.

Unless you've been hiding in a crater, you know that Mangalyaan catapulted India's space programme to international stardom.

In an astonishing 15 months from the day it was announced (by the then-Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, in a speech on August 15, 2012), the team at ISRO conceptualised, planned and implemented the mission, successfully sending off the autorickshaw- sized satellite out of Earth's orbit and into Mars', a journey of 660 million km and 300 days.

Armed with five payloads, including a methane sensor and tri-colour Mars Colour Camera, the satellite cost a total of US$70 million only. (For perspective, a similar NASA mission cost US$671 million; and the Sandra Bullock film, Gravity, cost US$100 million.)

The amazing success of the mission brought worldwide attention and not a small dose of national pride and glory. If geeks are now the cool kids, ISRO scientists like Dutta and Karidhal are worthy of prom queen status.

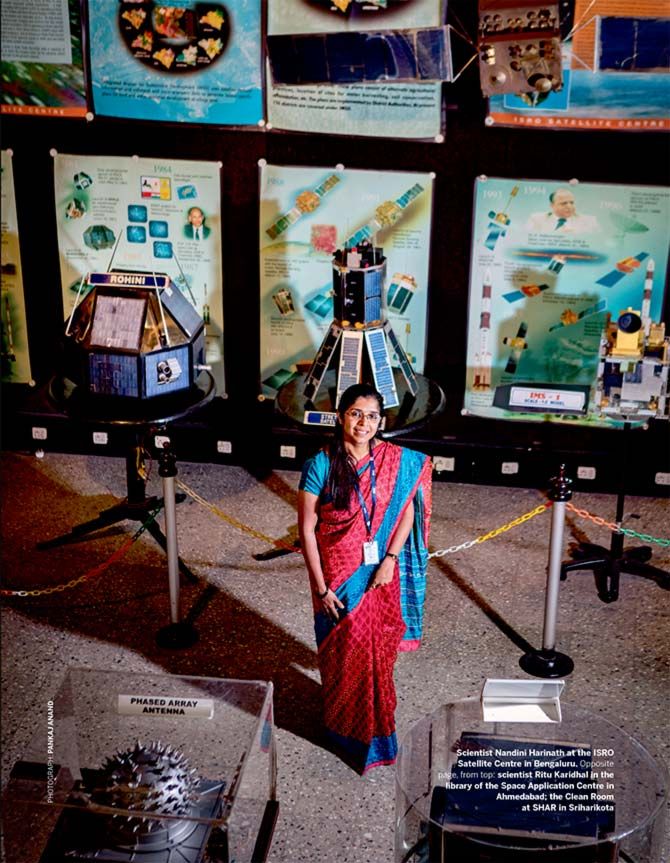

"I've worked on 14 missions over my 20 years at ISRO," says Nandini Harinath, who served as deputy operations director on MOM, "and each one you work on feels like it's the most important. But Mangalyaan was special because of the number of people watching us. And it feels great to be recognised for your expertise and competence. The PM shook hands with us. NASA congratulated us; they're now collaborating with us. But it's not just the industry, it's the wider public, institutions, schools -- they're all so interested! They're even following it on social media."

What we didn't follow were the demanding schedules, intense pressure and tireless effort along the way: consecutive 20-hour days of endless permutations and combinations and rigorous testing, and many heart-in-your-mouth moments.

The scientists are quick to dismiss it all, ("When you are working for a mission, for your country, whatever sacrifices you make seem worth it," says Dutta), but equally so to credit their cooperative colleagues, supportive husbands, encouraging parents (who never let them believe that girls were any different than boys, and continue to pitch in) and in-laws for pitching in to help with their kids.

Nandini's mother, for instance, would move from Andhra Pradesh to Bengaluru for a month at a time during satellite launches to help with Nandini's two daughters.

In fact, her elder daughter was studying for her 12th standard exams while Nandini worked on MOM. "I'd only get home around midnight, but I'd wake up at 4am so we could study together. Luckily, we were both too busy to stress each other out!"

Minal Rohit, a spunky 38-year-old project manager on MOM and mother of a six-year-old boy, has a unique approach to balancing work and family life.

"We think of our satellites and payloads as our babies, too," she says.

"To us, they have lives. So the rules for office and home are common: Patience, Procedures, Priorities. If you're patient, that's half the battle won. Don't allow for single-point failure; have backup plans in your mind all the time to avoid chaos. And you can't be everywhere at once; so assign your priorities. The mind and heart have to be in sync. You must always be true to yourself."

Still, all the scientists are clear that ISRO (whether in Bengaluru or Ahmedabad) is a brilliant work environment. "Nobody cares if you're a man or woman here," says the softspoken Karidhal.

"It's talent and good ideas that matter. There's equal opportunity."

Women constitute only 20 percent of ISRO's 16,000-strong workforce, but female engineers are increasingly joining in. "There's greater awareness and education among young women now," says Nandini.

"Parents are being supportive of their daughters pursuing careers.

The problem is that many highly educated women drop out before reaching leadership positions.

That's the mindset we need to change. Women have to realise that they can manage having careers and families. It's possible! You can do it if you want to."

The passion in their voices is palpable. Karidhal, Dutta, Nandini and Minal have all worked at ISRO for 10 to 20 years, and each calls it a "dream come true." (Dutta turned down a chance to pursue a PhD in Dublin while her husband studied for his in Spain; she moved to Ahmedabad instead, for her job. And Minal still recalls her father paying for her first-ever flight, to Bengaluru, for the job interview.)

These are women who clearly derive great joy from their professions, and speak of their research as having higher goals, of helping solve many of our current problems. "Satellite data can be used in so many ways to benefit day-to-day living," explains Nandini.

The examples are many: Ocean Colour Monitors help fisherfolk throughout India's 7,500km coastal belt locate areas with a high density of fish (they receive the information on their mobile phones); the Oceansat-2 Scatterometer measures currents to model and predict cyclone patterns to aid with disaster management efforts (as it did recently in Odisha); crop estimates are generated up to three months in advance thanks to Resourcesat imagery.

According to sources, the technology is boosting transparency in government by verifying claims made by states.

"Mangalyaan was a triumph, but we have a long way to go, a lot more to achieve," says Minal. Dutta agrees: "We have to think of space research the same way we think of parents going to great lengths to educate their children. The fruit will be harvested by others, but we must invest now for sweet returns."

Want your little girl to grow up to be a rocket scientist? Clearly you have to start her young -- and then get on board for the long haul.

Excerpted and published from Conde Nast India's Make In India magazine, a special edition which was launched on February 17.

The complete feature can be read in Condé Nast India's Make In India magazine

ALSO SEE

© 2025

© 2025