An organic chemist, she is best known for her path-breaking research that helped in developing chemotherapy and in epilepsy and malaria treatment.

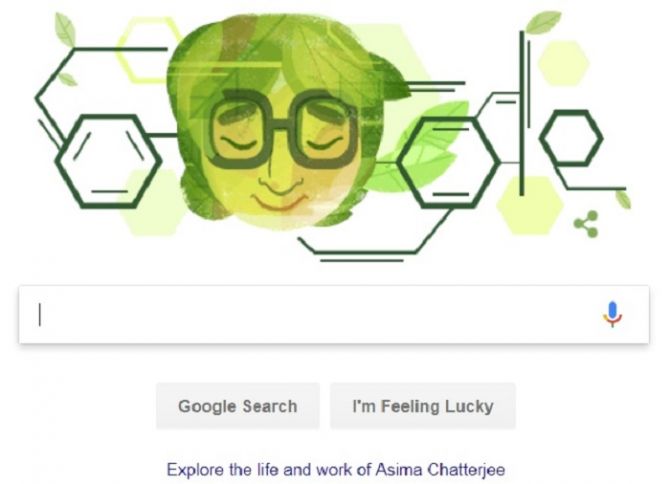

Here's 5 things you must know about the scientific trailblazer who inspired a Google Doodle.

We are still reaping the benefits of the rich scientific legacy of Dr Asima Chatterjee, but not many even know her name.

The Google Arts & Culture lab is trying to change that with its Women Scientists of India Series.

On September 23, the birth centenary of Dr Asima Chatterjee they got the world talking about her with a Google Doodle that linked to a digital retrospective her life and work. The digital exhibition 'brings together special family archives in collaboration with her daughter Professor Julie Banerji, and University of Calcutta, and Indian Academy of Sciences.'

Take a peek.

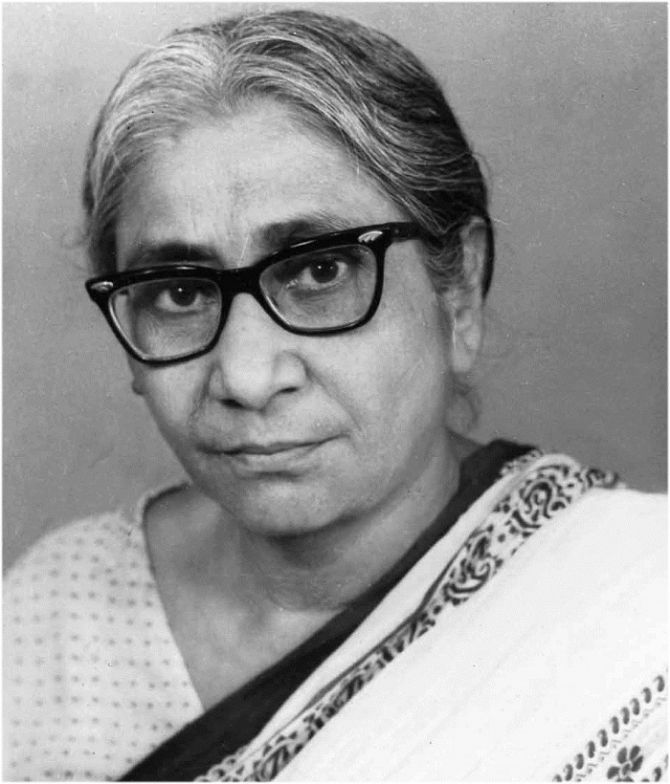

Photograph: Courtesy Indian Academy of Sciences via indian-scientists.padakshep.org/Wikimedia Commons.

1

Dr Asima Chatterjee's area of interest was natural products with special reference to medicinal chemistry. She made significant contributions in the field of medicinal chemistry with special reference to alkaloids, coumarins and terpenoids, analytical chemistry, and mechanistic organic chemistry.

'Besides her keen interest on fundamental research, Professor Chatterjee always stressed on the utilization of phytochemicals from indigenous plants as drugs and drug-intermediates,' Google noted.

Through her research activities, spread over a period of nearly 60 years, she made massive contributions to the development of chemotherapy and the treatment of anti-epilepsy and malaria treatment.

Google said, 'Chatterjee successfully developed the anti-epileptic drug, Ayush-56 from Marsilia minuta and the anti-malarial drug from Alstonia scholaris, Swrrtia chirata, Picrorphiza kurroa and Ceasalpinna crista. The patented drugs have been marketed by several companies.'

Forbes added, 'Her work on a group of chemical compounds from the Madagascar periwinkle plant, called vinca alkaloids, contributed to the development of drugs used in chemotherapy to slow the growth of some types of cancer by preventing cells from dividing.'

2

Asima Chatterjee was the first woman to be awarded a Doctor of Science by an Indian University -- in 1944, by the University of Calcutta.

She had graduated with Honours in Chemistry in 1936 from Scottish Church College and received the Basanti Das Gold Medal.

She obtained an MSc degree in 1938 with Organic Chemistry as special paper and received the Calcutta University Silver Medal and Prize and Jogmaya Devi Gold Medal.

Google said, 'She then started her research career under the able guidance of Professor Prafuila Kumar Bose, one of the pioneer Natural Product Chemists of India.'

Google added, 'In 1940 Mrs Chatterjee joined Lady Brabourne College, Calcutta, as the founder-Head of the Department of Chemistry.

'In 1944, she was appointed a Honorary Lecturer in Chemistry, Calcutta University.

'In 1947, she left for the USA on study leave from Lady Brabourne College.'

Between 1947 and 1950, she worked on Naturally Occurring Glycosides at the University of Wisconsin, on Carotenoids and Provitamin A at California Institute of Technology in Pasadena (earning a fellowship) and on Biologically Active Indole Alkaloids -- 'which became her life long interest' -- at the University of Zürich.

Google said, 'After her return to India in 1950, she started research on alkaloids and coumarins with renewed vigour.'[

3

Not surprisingly, it was not easy being a woman scientist -- or even a scientist -- in India.

Dr SC Prakashi, one of her early PhD students who closely witnessed her initial struggles to establish herself, told Google: 'Those were trying days for research, particularly in the most ill-equipped university laboratories with inadequate chemicals and meager financial assistance. Institutions such as the Department of Science and Technology or Department of Biotechnology under the Government, were yet to come and Council of Scientific & Industrial Research (CSIR) was in the formative stage.

'Research guides had often to pay not only for chemicals, apparatus, etc., but also the charges of even elementary and almost all spectral analyses to be had from abroad.

'Scholarships were few and barely enough; most of the students had to work part time or without any scholarship just for the love of work and pay all the necessary cost of thesis submission, including printing, examination fee and even the postal charges for dispatching the thesis to the foreign examiner(s) which was compulsory, with hardly any job prospect for research as a profession.

'Before I joined her, she had a grant of ₹300 per annum. and three college teachers as part time research students. I was the sole fulltime scholar with laboratory grant of ₹1000 p.a. only with a princely W B Govt stipend of ₹150 per month. For milling plant materials we had to go to the far away workshop of the Jadavpur University and even for UV measurement, we had to go to adjacent Bose Institute where only she was allowed to handle the equipment.

'We borrowed solvents for plant material extraction mostly from the comparatively well off BC Guha's [the father of modern biochemistry in India] laboratory as the research grant of even the Heads of Departments used to be only ₹1,200.'

This struggle took place even as Dr Chatterjee did all that was expected of a home maker in those times. Google noted, 'She would rise up early in the morning and would complete all household chores, including cooking, before she left for the University. On returning, late in the evening, she would again return to house-work.'

4

During those hard days, Dr Prakashi told Google, 'She received encouragement from Professors Satyen Bose, Meghnath Saha, S K Mitra , B C Guha and Sir J C Ghosh and other Vice-Chancellors of Calcutta University. Her husband, Professor Baradananda Chatterjee, a renowned Physical Chemist himself and the Vice-Principal of the then Bengal Engineering College (now a Deemed University), Sibpur, Howrah, solidly stood by her.'

Dr Asima Chatterjee (nee Mukherjee) had married Dr Baradananda Chatterjee in 1945 and they had one daughter, Julie. He had a profound influence on her life.

'Without his constant inspiration, encouragement and co-operation,' Google noted, 'it would have been impossible for Mrs Chatterjee to dedicate herself to the cause of science. Members of Prof Chatterjee's laboratory considered themselves as one large family and to this her husband had much contribution. On Saturday evenings as well as on holidays he used to come to visit them. Often her students discussed with him certain problems which they felt shy to bring to the notice of their teacher. They considered him as their friend and well-wisher.'

5

Dr Asima Chatterjee was the first woman to be elected as the General President of the Indian Science Congress, a premier institution that oversees scientific research.

She also won awards like the S S Bhatnagar award, the C V Raman award, and the P C Ray award.

She was a recipient of the Padma Bhushan.

Google added, 'She published around 400 papers in national and international journals and more than a score of review articles in reputed serial volumes. Her publications have been extensively cited and much of her work has been included in several textbooks.'

She passed into the ages on November 22, 2006.

© 2025

© 2025