'From the beginning (I have told her) "Whatever it may be -- you are losing or winning -- on the ground you're not going to cry!" She never cried.'

'"I don't want you to project that you are a loser. You are a winner".'

Vaihayasi Pande Daniel/Rediff.com speaks to Leela Raj about her famous daughter, now in the West Indies for the women's T20 World Cup.

I met Leela Raj for three hours a few months ago in Secunderabad.

You have, undoubtedly, met a woman like her too.

In your own home.

She is the archetypal Indian mother.

Her brown, capable hands, with their few strands of red sacred thread and the gold bangles tinkling at their wrists, a gold ring on one finger, are so very like the hands of the mother who always toiled for you, night and day, often renouncing so many of her wants and ambitions for yours.

They are hands you admire from the bottom of your heart.

Leela's are the hands that nurtured, raised and launched India's finest woman cricketer.

For Leela is Mithali Dorai Raj's mother.

Mithali is, of course, the highest runs scorer in international women's cricket.

When you hear Leela's story of patient grit and slog you aren’t at all astonished that Mithali is one of the most successful women cricketers in the world.

Leela is a simple South Indian woman, of Tamil heritage and Andhra domicile.

She is warm. Lively.

Plenty resilient too.

She giggles, often uproariously, as she recounts the courageous tale of bringing up a cricketer daughter in a land that was no country for women cricket players.

As you look around the plain home, located in a colony in Trimulgherry, north of Hyderabad, where an array of pictures of Mithali, with her powerful eyes and winning smile, dominate nearly every shelf and wall, you realise a simple secret of life.

You understand, in one swift moment, what enduring, selfless and almost magical parental love can achieve. You are awed.

It can move mountains, make the impossible possible and raise right-handed first-class world-famous batting heroes.

Mithali, Leela tells you, as a youngster, quite serendipitously strayed into cricket.

The little girl, their youngest, always enjoyed her sleep. Her long sleep-ins created havoc in the family's daily routine.

Warm summer mornings the Raj family usually briskly set out for son Mithun's 6 am cricket coaching class at St John's Academy nearby, before heading off to office -- Leela worked with the engineering instruments division of Lawrence and Mayo; husband Dorai was with Andhra Bank.

But Mithali didn't want to get out of bed.

"This girl, she was very lazy in the morning. Morning she loved to sleep. That morning sleep. We shouldn't disturb her and all that. That became a big nuisance for us. We're all early risers. This girl wouldn't get up from her sleep. Even if she did, she'd been in a cranky mood because her sleep had been disturbed," the mother remembers.

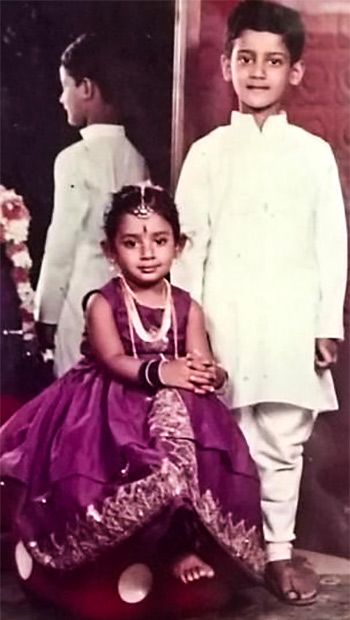

About as much as her sleep, Mithali loved watching what her dearest Bhaiya was up to. Born in Jodhpur, where Dorai was on his last Indian Air Force posting before he joined a bank in Hyderabad, Mithali grew up calling Mithun her elder brother by the north Indian nickname bhaiya.

She also grew up wanting to follow him in whatever he did.

"She had this one thing, you know, if my brother is doing something, I should do it too. It was with her fighting spirit."

The prospect of watching Bhaiya take part in a summer cricket camp proved more attractive than sleeping late.

Leela had to only tell Mithali that they were going to check out Mithun playing and the girl jumped out of bed and road on the back of her dad's Jawa motorbike, accompanied by her pillow, dozing for the precious last few minutes, to the cricket ground.

"He (Dorai) used to take her. When she opened her eyes she would see the ground. (Laughs) So that was her thing. Then they used to sit on the boundary and he would just be teaching her some math or some simple things. He cleaned his motorbike and this boy used to play. So whenever the ball comes she used to throw the ball back."

To humour Mithali, while the boys practiced, Mithun's coach Jyoti Prasad would often play a side game with the six year old, throwing her balls to a little bat she borrowed.

"Then that Jyoti Prasad started watching her. Five minutes only. Not much. before all the boys could do their fitness, he used to just entertain her for five, 10 minutes, just throw the ball and say you should hold this. She had that grasping power. He started enjoying teaching her. He noticed that after two, three months this girl really picked up... Just casual it was. Five-ten minutes, not more than that, till these boys finished their warm ups. So that continued for a month or so."

By the end of that summer two things were obvious.

Firstly, murmuring the word C-R-I-C-K-E-T quietly in Mithali's ear could get her jumping out of bed in a trice.

Secondly, Mithali was born to the game.

In a casual remark that forever changed Mithali's life, Mithun's coach mentioned to Dorai "Instead of concentrating on your son, I think it's better you start concentrating on the girl, he point blank told."

Prasad advised they immediately put Mithali into coaching and suggested a National Institute of Sports coach named Sampath Kumar, who he warned was crabby, difficult but a hard taskmaster.

So off Mithali went, rag-tag, but deliriously happy in Mithun's castoff whites, to learn to bat, ball and field at the tender age of eight.

Mithali had been venturing to Kumar's girls' cricket Sports Glory Club for about two months when Sampath noticed her.

"He called my husband and said this girl is good. I am planning to make her play for the country. Now you tell me? How would you feel (if someone told you that)? But in the same tone he said this girl has got that thing (gift) to play for the country, provided I can do it. But I need, as parents, your cooperation. That is a must."

Initially, the Rajs didn't take Kumar seriously.

They talked it over amongst themselves. Mithali had been with Kumar for just two months. They felt he was simply talking big. Boasting. The couple decided not to think about it anymore and ignored what Kumar was asking of them.

"We took it very light because see somebody saying, within two months, I'll make your daughter... How will you take it? Just couldn't take it. My husband being very practical, he just left it. He didn't argue with him much."

The coach didn't let it be.

He again told Dorai and Leela: "'She is playing-for-the-country material. I, as a coach, I can take the challenge. But as parents, I need you guys also then only we can work on it... I will want her to play for the country when she's 14 years. Sachin Tendulkar had a record. So why not we make this girl?'"

It was customary for Dorai to drop Mithali off for her morning round of coaching. Afternoon coaching began at 4 and Leela would arrive there by 5.30 pm, after work to watch tiny, diligent Mithali at her sport for the next one-and-a-half hours.

Kumar used that opportunity to chew away at Leela, "I would sit down and watch. He told me why (he felt that way). He also told me, 'See, I'm going to make your daughter play for the country.' I said, 'Come on, please don't pull my leg. If there is something else to discuss, let's discuss. Let's not discuss this because that's not going to happen'."

"'No, no. Why are you saying it's not going to happen?'"

"'Sir, just three months, she's nine years old. How's it possible that you are saying this?'"

"'No, this girl has extraordinary grasping power. Extraordinary, I should say...' He told me because of her grasping (power) she just catches on. That talent she's got. 'That talent we make use of it. As a coach, I will give my 200 per cent. This girl is ready to give me (the work). But you guys... because once she's at home, you're very important (to give her that) mental balance. That is more important'."

"Then he spoke to my husband... He said, 'See, you guys are thinking very, very average thinking. Why don't you think (more boldly)? See, I'm telling you she will play for the country when she is 14 years, if not 16. Even if I'm making a goal of 14 years, maybe if for some reason at 14 (it doesn't happen) at 16 she will do it. That is my target. We don't target high. You target 14 and then if that doesn't work out at least 16, it's not going beyond that. That's how you plan it'."

Meanwhile, Leela recalls, Mithali's graphs were moving dazzlingly upwards to their astonishment. At barely 9, she was, straight away, selected to play for the state in the sub-juniors tournament. She was, of course, the youngest.

Slowly, but surely, Coach Kumar's words were proving true.

The routines in the Raj home began to change.

First they had to move out of their joint family. Mithali required a special diet, with a heavy emphasis on dry fruit, and the family needed the mental space to help her work towards her career goals.

What Kumar wanted was not something they had envisioned any daughter of theirs would be striving for. It was something they could hardly believe.

But they had to.

Because Kumar believed in Mithali.

Leela and Dorai, each for their own reasons, were keen to see Mithali pull it off in cricket.

Leela felt that through her own childhood, though privileged, no one had pushed her enough to reach her potential. She had been interested in dancing. But her life goals went by the wayside because she had been too protected and not been inspired to perform or persevere.

For Dorai, who was crazy about the sport and once played cricket for the Indian Air Force team, it was about his disappointment at himself for not realising his own cricketing ambitions. He just hadn't dared to dream.

Dorai and Leela wanted Mithali to dream. To soar. And succeed.

Not surprisingly Dorai's mother was appalled. "My mother-in-law was dead against it... She said 'How long is she going to play after marriage?' When she went into cricket she told my husband, 'Why do you want that girl to play cricket? If she gets hurt who will marry her' and all that stuff."

When she was chosen for the sub-juniors, Mithali was expected to travel to Jalandhar, nearly 2,000 km away, with her team for the tournament and be away from home for ten days.

That was when the reality of Mithali's new life hit home.

Leela got more and more anxious about the enormous trip her wee nine year old who had never been far from her, was about to undertake.

How would she survive so many days away from home? Especially given her food habits.

Who would take care of her beautiful long black hair?

Who would ensure that her little girl, who still loved her sleep, didn't go to sleep in the wrong place?

It was a very nervous and fretful Leela who put Mithali on the train at Secunderabad station for Punjab. She implored her team-mates to make sure Mithali didn't fall asleep in the train bathroom and asked if someone could take care of her hair.

There were no cell phones or ready access to STD lines those days. Leela sent along one of those thin, blue inland aerogrammes with Mithali, in her luggage, and asked her to post it when she reached and tell her she was safe. Which she later did.

"When we came back home (from the station), I cried. That was the first time I left her. So my husband said, 'See if this is what you are going to do it, then we will go and bring her back. No problem. We will go to the next station and bring her back. You decide. Fast. Think it over. If you want to make your daughter something then forget this. Or forget that you are giving your daughter to the country. You want to do it, just stop crying. Otherwise we'll go ahead and bring her back. No problem'. Then I wiped my tears."

In that moment Leela realised she had sacrificed her daughter to a sport.

To the state. Perhaps the country.

She had well and truly become a cricket mom.

If the ten days Mithali was away were misery for Leela, Mithali was enjoying herself, her first taste of freedom.

Remembers Leela: "When she went there, she did all her things. What she couldn't do, like wear her long hair open, which Dorai strongly disapproved -- We got a photo of hers taking the memento for the tournament with her hair open!" She laughs hugely at the memory.

From then on, Mithali was in and out of her home for more than 15 to 20 days in a month, travelling the length and breadth of the country for matches.

For the sub-juniors, the junior team and the senior team, all of which she had qualified for one by one. It was a non-stop whirl,

It was also always last-minute travel. The day before they were meant to leave for a tournament, the coach, having found, in the nth hour, a sponsor, would produce the tickets and they would travel unreserved second class, the entire team, of which Mithali was usually the youngest, piling into the coach.

Leela didn't worry about the travelling. She knew they would be safe together.

She worried, as all Indian moms do, about her food. Like any proper South Indian Mithali, lived for her "thick curds-rice" a commodity hard to come by in the sparse hostels where they were put up for tournaments.

"When she came back, she would come dark and thin, just like a Sri Lankan refugee. (I would say) 'What is this?!'"

At home, between tournaments, it was relentless practice and General Leela was in charge.

Minimum six hours a day, usually much more. Morning-evening practice with Sampath Kumar. Practice camps with the team. And physical fitness too.

When Mithali was at home, Leela had to make sure she did some rounds of hanging ball cricket. It was not some sort of hi-tech exercise. A rope hung in the middle of the home, on which a sock, with a ball in it, was tied.

Mithali, in her spare time, which was nearly non-existent, had to brush up her batting by taking whacks at the sock.

Leela in her spare time, which was equally non-existent, would be conjuring up nutrition-rich food for the young sportswoman -- special milk drinks with figs mashed into them and nut-based items.

Mithali, says Leela, never shied away from hard work: "Like, you know, she could have also said, 'No Mommy, I don't want to go'."

"But till today she has never said that when it came to cricket. I don't know why. She never has said that. I don't remember her saying at any time that I don't want to go for today's practice. She always loved it. Yeah she would never say that I don't want to go. She has never said that for practice or anything. Never, never, never, ever."

By then Leela had quit her job. Coach Kumar demanded she do so.

"Mithali got selected for the juniors and it became very hectic. After the sub-juniors it was the junior tournaments. So she goes there also. This continuous process... We started seeing the graph of hers going up. We believed in him (Sampath Kumar). Then a little belief came then, yes."

"One day he called. I was still working. 'See listen', he told my husband, 'I think it is better your wife resigns her job. This girl needs a good diet when she comes home. You should give her hot, hot food. See that she never has an empty stomach. Put her to sleep, because again she should be prepared for the evening session. This all can happen only if she's at home. You can't just leave the girl and say, "You do it, to eat this". No, it's not like that'."

"He personally told me too, in the same words. He said, 'What you are earning is peanuts. Your daughter is going to give you more. You get prepared. People will come to you for interviews. For your daughter also I have to teach her how to talk'."

His words must have stung a bit at the time. But Kumar was not in a habit of varnishing the truth. Leela acceded.

From then on, Mithali's time had to be carefully utilised and its usage intricately balanced.

Kumar instructed that Mithali, a growing teenager, needed small, nourishing not heavy meals every two hours to prevent cramps. And her full quota of eight hours of sleep, something Mithali did not have to be persuaded to seize (Or as Leela puts it, "I think that's God's gift to Mithali. Sleep").

He also dictated that Mithali should never travel by public transport so Leela drove Mithali to practice on a two-wheeler.

Giving up her job put the family in a spot of financial difficulty.

Dorai had just moved them away from the family house to a new flat bought on loan. Two incomes were a must in perpetually inflation-ridden India. Keeping Mithali in shoes and kitted out was a sizable expense. She needed a new pair of shoes, equipment every three months, apart from the travel and diet expenses.

But Kumar's advice could not be ignored.

The Rajs looked into ways to tighten their belts without hindering Mithali's progress.

Mithali's game came before everything else. It ruled their lives. No sacrifice on the altar of cricket was too great. Hat tip, to Mr and Mrs Raj.

"We decided that for the first four years we shouldn't go for any (new) clothing, no celebrations, Diwali and all that. Just minimum requirements, what we needed. All funds were for her and for the school fees for both the children. Whatever minimum we can do. We cannot cut on food, both the children are young... So these were the things, the minor sacrifices we made... For one year we struggled like this, you know, cutting (back) slowly on everything, wherever we could cut. Then I resigned my job."

Financing Mithali's sport proved tremendously taxing, all through, but Leela and Dorai always found a way. In those days there was no BCCI or any other organisation to help these brave, sturdy women's teams.

Funds of any sort were in short supply, if not fictional. Expenses climbed, especially when the teams were on tour for tournaments. Parents had to chip in, in various ways.

Even as Mithali threw herself into her tournaments -- juggling her assignments for different teams -- the 1997 World Cup was approaching.

Mithali, a tender 14, had, of course, caught the attention of selectors for her effortless batting style and for her shrewd knack of using the pace of a bowler.

Much to the elation of her parents and Coach Kumar, Mithali was selected as a probable.

Remembers Leela, "That man (Kumar) was very much happy. He knew that she had made it... The captain Pramila Bhat told the papers that there's one small little girl, who is 14 year old. She's from Keyes High School who is going to make her debut in this cup."

Mithali finally didn't make it to the team though she remained the first probable because they felt she was too young to take the pressure.

The intervening year after that, she had a bit of a setback, that was source of great anxiety to her parents, when it didn't seem her cricketing career was going anywhere, till she began representing on the domestic scene first Air-India and later the railways.

Two years later, in 1999, as Kumar had so smartly predicted, she made her one-day international debut at Milton Keynes, England, in a historic match against Ireland where Mithali scored an unbeaten 114 at the young age of 16. Unfortunately her coach had been killed two years earlier, tragically, in a freak accident.

Sending Mithali on her first trip abroad, while a moment of triumph for the Rajs, had its own how-will-my-little-girl-cope-so-far-way anxieties for Leela and financial challenges for Dorai.

Dorai had to scare up the money to finance her expenses there. Her ticket was covered and so was her lodging, but not her daily expenses. Says Dorai: "You will not believe... I had to borrow Rs 25,000. They said 'She is going to England. Only up and down air fare and accommodation was covered. Rest all you have to take care of. Minimum Rs 25,000 they should carry.' So I borrowed money."

Mithali and her fellow team-mate from Hyderabad called home to say they had reached and were safe. Then to Dorai's irritation they complained about the unpalatable English food.

He ticked them off he says, 'You are talking about food? Forget about food. Think about your game. When you are eating think about India, your game and all. You will not understand what you are eating. If you see what you are eating then you cannot eat'. After that trip she never spoke about food difficulties to her parents again.

Mithali never looked back after that tour.

Her Test debut was in 2001 against South Africa in Lucknow. In her third Test she scored 209, breaking all records. She took her team to the 2005 World Cup final and has captained a World Cup team more than any other female or male player.

In 2006, she led the Indian to a series victory against England. India won the Asia Cup in 2006 too. She is the only woman cricketer who has gone past the 6,000 run mark in WODIs, the first to score 7 consecutive 50s in ODIs and has hit the most half-centuries in WODIs.

Her Secunderabad home overflows with every kind of trophy and photographs with a rainbow of VIPs including Prime Minister Narendra Damodardas Modi.

Could Sampath Kumar have been more right?

Could Leela together, with Dorai, have raised a bigger star?

Is there anyone who has changed the way Indians look at women's cricket more than the feisty Mithali Raj?

Mithali right from her debut days attracted notice for her maturity as a sportswoman.

Being talented from so young had its advantages: She was always pitted against players much older than her and moved in the milieu of teams, where she was often almost 10 years younger than her fellow players.

Dorai also always had her practice her batting with older boys he co-opted for the task.

Says Leela: "She matured very quickly. Mentally, her maturity was tremendous. Beyond her age. It was good. She knows when to use her head. That was more important."

In addition to cricket, Mithali was still pursuing dance, parallel with cricket, for many years, right till Class 8. She had started Bharata Natyam even before cricket and was an accomplished dancer.

Leela was keen she kept up her dance too. So was Mithali. "She used to really take interest. She was a very graceful dancer."

But as Mithali's cricketing career picked up tempo it became increasingly difficult for her to juggle both pursuits. That she had been able to till then was in itself amazing, a feat no less.

The day Mithali bid adieu to dance and surrendered to cricket might have been a scene out of a film titled Two Loves.

Mithali's dance teacher and cricket coach never liked each other much. And they had a nodding acquaintance given that both conducted their classes from the same premises, the Keyes High School, the school Mithali attended.

They had quarrelled over their star pupil. "There used to be a fight between the coach and the dance teacher. You have taken my very good student, she (the dance teacher) would always complain."

Matters came to a head when an important dance performance Mithali had been tirelessly practicing months for coincided with a cricket tournament, whose dates came up last minute.

It so happened Mithali was due to leave for a match in Bangalore and a Margazhi season of dance performances in Chennai on the same day.

As Leela remembers it, on one platform a train was waiting to take her to Chennai. On another platform was a Bengaluru-bound express.

Mithali was literally was at a crossroads.

She had to choose which train to board. Which which train would take her to her future?

Cricket won out.

Mithali headed to Bengaluru.

Leela reflects that Mithali never ascribed reasons for pursuing cricket as a career.

She only always said: 'I did it for my dad. She's been saying. But even if you do it for your dad you don't do (so much)! Sometimes her dad kept giving her challenges. 'You can't do it, you cannot do it. Stop it'. That was the thing. She wanted to prove him wrong. So she will do it. That was a challenge for her."

Leela says Mithali just takes things in her stride without assigning too much emotion. "This girl was very, very, very practical I can say. Her emotions are very down to earth. Like she doesn't give her emotions. No, no. Either negative, positive or excited. Nothing. Only in her tone I can make out that yes, she's excited, she's happy or she's sad... Otherwise, she doesn't show any of her emotions. Even when her coach expired. Only thing was like: 'How am I going to practice?'"

Nor did she ever complain about anything. For many tournaments Mithali barely had two changes of clothes, beyond her kit/whites, because the family could not afford any more than that. It didn't bother her. "It was like she knew what she had to do."

Apart from dance, Mithali's studies were another casualty of cricket; another demand the sport made of her.

The girl, says Leela, was a good student and all through school, who caught up with her studies in any free time away from the crease/field. She studied on trains going to tournaments and at her lodgings. Leela always sent a few books with her, suggesting she spent any idle moments having a look at her books.

She, with much credit due to her proud school for their unstinting support, finished her 10th class school-leaving exams, with and started her intermediate at the Kasturba Gandhi Junior College, but was unable to get around to going to senior college. Her dad says, "She is still studying," referring perhaps to the fact that Mithali loves to read.

Cricket was merciless in other ways too.

In a country like India, a woman cricketer is not an entity that many understand. Or have even heard of.

While male cricketers are fawned over and worshipped, how many understand what it takes to groom and raise a woman cricketer?

The struggles. The heartache. The prejudice.

The fight for recognition and fame to bring much-needed funds.

How many reports about women cricket have you read in the pages of your national newspaper or hear on television?

How many women cricketers had you heard of before Mithali happened along?

The question Leela fended off most often, most of her life was when would Mithali settle down.

The word 'settle' sets Leela's teeth on edge. She is at pains to explain how crude and illiterate attitudes are, something that probably every Indian sportswoman faces.

"Settling is different for each individual. For us, I think, it is only marriage. They don't go beyond that. People, now also, they ask me, 'Arre, the only thing now if your daughter gets married, life is settled'."

"What life settled?! My life is settled already! I don't have to settle her! They don't go beyond that. They think marriage is the end of life."

"Both my children I told: 'See marriage is not important in life. It's a part of life. You want to take it and go along with it, fine. If you don't want it also, it is not that important...'"

"Somewhere down the line you have to give away one thing, if you want to go to a higher level. If you want to be average, you can continue both. But in some way you want to be extraordinary, you have to give one thing. So my daughter sacrificed that."

When Mithali crossed 24 and 25, it did stray into Leela's mind that perhaps she might meet someone. "The one thing my daughter always cribs: 'Mummy you put me in a girls school. You put me in a girls college and you put me in a girls team where I don't interact with boys. Now how can I get a boy? Every time I practice it is always with girls and where can I get a boy?'"

"People would question us: 'What as parents are you doing?'' Definitely I would like my girl to get married. But that doesn't mean that I just push her in. Settlement bola toh marriage, ya anything?!"

"Things will fall by the wayside. Either the sport can fall or marriage. Anything can fall. See I'm not talking only about sports. Even academics."

"Seriously I'm telling you, we definitely looked out for her boy when she was 24, 25. We interacted with parents. She was still into actively playing. She was not taking her retirement (say) in some few months. Nothing like that. She was serious into cricket."

"So I was looking into a family that was open too. The parents were often very cooperative."

"But the boy, when he would speak to Mithali -- there were two-three boys -- who started questioning her: 'How long will you play cricket? Or see I am in the merchant navy, so you will have to see my finances'."

"One boy told her: 'Hey look, listen, playing cricket is one thing. Next thing, suppose we have babies, I'm not going to do any diaper cleaning. Nothing I'm going to do. Totally you only have to do'. And the third thing he told her: 'I want to ask you, suppose my mommy's sick and you have a tournament, a match to go to. Are you going to go to the match or look after my mummy?'"

It was idiotic questions like these that drove Mithali up the wall, remembers Leela and she would tell her mother: 'This is cricket I am playing. Will they put the same question to a boy. If a male cricketer is playing will a girl put these questions?'

Leela never watches Mithali play. Neither on television. Nor does she go to a game.

She has a thing about it. Not really a superstition. It is not about luck either. She is not exactly able to explain why. Maybe it is her grudging way of showing Cricket it ultimately doesn't own her life entirely.

The one and only match she ever attended was one her husband played, just after their marriage and she recalls sheepishly, she fell asleep halfway through.

Leela claims not to dislike the sport that rules her life. She also says she doesn't understand it much, although the thorough Sampath Kumar made it a point to teach her all the fundamentals of the game so she could supervise Mithali's practice. "That man used to eat my brain. He has taught me. Like homework."

July 23 2017, the day the entire country, and some of the world, was super-glued to their television screens watching Mithali and her team play the women's World Cup final, at Lords, against England, with bated breath, Leela wasn't watching, of course.

Sure the television was on, as it usually was when Mithali was playing, at the Raj home in Secunderabad. Hundreds of supporters were dancing and cheering outside the house (Recalls Leela irritatedly, "They were saying 'Arre they lost theek hai. Even if they lost, they won for us,' they did it and all they were dancing and all that.")

The media was there too. But Leela wasn't watching.

The World Cup final, that Mithali had shepherded the Indian team through the tournament to, that India lost by a disappointing 9 runs.

Some 180 million the cricketworld over,ing it was estimated, watched that game. Everybody Leela knew had watched Mithali in that final.

Leela's little grandchild Anaga was cheering her Bua on, because the little tot was of the firm belief that if she cheered her auntie in blue, then only would she win.

All the women in Leela's kitty circle. Even her most distant relatives. Even her help told her she had seen Mithali play.

The match Leela decided to finally watch was the replay of that final.

Not because she was trying to get a feel of that historic game or she had succumbed to the sport's charms. "Because what happened. People said because of Mithali only we lost all... Mithali did like this, that's where they lost. What nonsense. (Like there is only) one Mithali. Everything Mithali only. Other girls also. It is not an individual game."

"I was not interested whether we lost or anything. I was only watching to see whether Mithali is going to cry there. I'm dead against it. I keep telling her: 'You are not going to cry. From the beginning (I have told her) Whatever it may be -- you are losing or winning -- on the ground you're not going to cry!' She never cried."

"I taught her this. You never show your weakness to others. I never liked her crying and all that rubbish because I told her if you are crying is like you are losing. I don't want you to project that you are a loser. You are a winner."

Leela is still very the cricket mom.

Dorai jokes: "She (Mithali) never tells us anything. She (Leela) is her local manager."

Leela keeps track of all of Mithali's appearances and schedule. And orders her life. Mithali recently tweeted: 'My RoleModel, My GuidingStar, A True #SuperWoman. Thank u Mamma for all that u've done and continue to do, I'm truly blessed to have u!'

Mithali -- who calls Leela 'Momsy' ("Momsy when she is in a nice mood. If there is a little problem I can be called Mummy. Otherwise Momsy, Momsy, she will be eating my brain") -- calls from abroad seeking her advice on clothes or shoes she is planning to buy. Or relies on Leela to help her execute a new diet plan.

Dorai, who takes Mithali to the airport when she travels and picks her up on her return, has been Mithali's strategist and advisor right from the start. The man Mithali would consult if she is wondering whether to bat or ball after the toss in the next game. Or who organises a special fitness camp for her.

Their life continues to revolve around Mithali, the daughter they gave to cricket and to India.

Says Leela: "Even now, today, when she comes home, she will be the same Mithali to me. Only thing now she doesn't have time. Otherwise she's the same Mithali, sometimes dumb and all that stuff (Laughs). Yes she is the same Mithali. She's so much into cricket life. Other things she's has no idea of in life, which sometimes troubles me a lot, of late."

© 2025

© 2025