Photographs: Jay Mandal/On Assignment Shashi Tharoor

In this special feature, Exclusive! to Rediff.com, Tharoor recounts his first encounter with the glorious game when England toured India way back in 1963 when the future Thiruvanathapuram MP was a mere lad of seven, and looks back on the India-England cricketing relationship which celebrates a hundred Tests at Lord's this week.

The story of the last five decades of Indo English Test cricket is also my own story as a cricket fan. I was introduced to Test cricket one sunny afternoon in Mumbai, by an indulgent father, at age 7. This was in the lovely Brabourne Stadium in late 1963, when a depleted English side were touring under Mike Smith. The Englishmen were so ravaged by an assortment of maladies that they played both tour wicket-keepers and enlisted the fielding of the Indian twelfth man, Hanumant Singh, who was to go on to score a century on debut against them in the next Test.

Whatever the strength of the visitors, though, the cricket on the third day of the Test was marvellous. I watched with enthralled seven year old eyes as Budhi Kunderan, India's opening batsman and wicket-keeper, who looked like a West Indian and played like one, pulled Price, England's fastest bowler, for six over square leg, the ball landing practically at my feet. He almost instantly repeated the shot, this time just failing to clear the rope.

In less time than the difference between a four and a six could be explained to me, Kunderan was 16; but he tried it too often, sending up a skier that swirled up in a gigantic loop over mid-on. As the ball spiralled upward, Kunderan began running; when it was caught by a relieved Titmus in the deep, Kunderan continued running, hurled his bat up skywards with an exuberant war-whoop, caught it as it came down and ran on into the pavilion. It was exhilarating stuff, and I was hooked for life.

The 1963-64 series in fact produced five draws that few pundits would classify as memorable, but it epitomized some of the best things about Indo-English cricket. It was played in tremendous spirit throughout, as befitted a post colonial relationship bereft of rancour (India had, after all, invented the formula which allowed it, as a Republic, to stay within the Commonwealth). The players and the crowds were equally cheerful, and the Indian twelfth man, Hanumant Singh, fielding for England in the Bombay Test, was only one of many gestures of sportsmanship and co-operation between the sides.

When the Kanpur Test ended, for instance, Pataudi was 199 not out, but before the umpires could remove the bails Titmus grabbed the ball and sent down a friendly long hop so that the Indian captain could complete his maiden (and as it happened, only) Test double century. It wouldn't have happened in an Ashes encounter nor, I dare say, in an Indo-Pakistan Test.

Cricket probably remains, along with the English language, the railway system and the Indian army, the finest legacy of 200 years of British colonialism in India, one of the few areas in which imperialism gave more than it took. Like the other remnants of the colonial presence, cricket has been thoroughly Indianised without losing its essential British moorings.

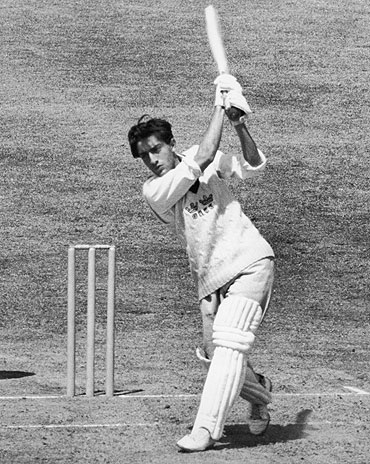

'The Nawab of Pataudi and Headingley'

Image: Mansur Ali Khan PataudiCricket is now an Indian game; many who play it have no sense of owing it to England. Yet just as Indian nationalists used British traditions and institutions to overturn British rule, so also Indians have taken up an English sport and delight in beating the English literally at their own game. While contests with the country's Siamese twin, Pakistan, generate more intense passions, it is still true that few sporting triumphs are regarded with more satisfaction by Indians than a cricket victory over England.

For years such victories were slow in coming, except at home, where before my first series Indian teams twice defeated English touring sides that were at less than full strength. But in England the pattern was depressingly familiar. When 5-0 whitewash succeeded 5-0 whitewash, Lord's decided it could only invite India for a three Test series, but even then, in 1967, India fell at every hurdle, a magnificent fightback at Leeds notwithstanding. (That was when the Indian captain, following on and in a losing cause, stroked a 148 so memorable the Daily Mail dubbed him "the Nawab of Pataudi and Headingley".)

The post colonial reality appeared to reflect the coloniSed past: The rulers continued their dominance over their former subjects. I had to wait till 1971, the annus mirabilis of Indian cricket, for the first Indian Test (and series) victory in England, when Chandrasekhar's 6 for 38 bowled England out at the Oval after two draws and made it to the front page of all the Indian papers. Earlier that year we had beaten Gary Sobers's West Indies 1-0 in the Caribbean, so for a brief while we were able to go around calling ourselves the world champions of Test cricket.

In 1967, at a time when drought and famine had reduced India to dependence on foreign, including British, aid, we had sent to England a side of talented batsmen whose gifts outshone their performance, an array of spin bowlers who plied their craft in conditions ill suited to their genius and a pair of pacemen so woeful that Pataudi felt compelled to open the bowling himself with his reserve wicket keeper (Kunderan).

By 1971, a year of victory in war as well as cricket, the balance was redressed: two "Little Masters", the great Gavaskar and the virtuoso Viswanath, brought solidity to the batting and two all-rounders, Abid Ali and Solkar, proved they could do more with the new ball than take the shine off it for the spinners. The fabled spin quartet (Bedi, Chandrasekhar, Prasanna and Venkataraghavan) were at their peak, as were 'keeper Engineer and batsmen Wadekar and Sardesai. When England returned the visit under Tony Lewis in 1972-73, they took a Test off India but were emphatically beaten in the series.

Gavaskar's extraordinary 221 restored national cricketing pride

Image: Sunil Gavaskar during his record breaking double century against England at the Oval in 1979Roy Ulyett drew a painfully pointed cartoon showing a lady addressing a middle aged gent outside the Gents' at the ground: "I told you, you should have gone earlier: you've missed the entire Indian second innings."

That was when I seriously wondered whether tennis might not be a more worthwhile sport for an Indian chauvinist to follow: At least Vijay Amritraj had made it to the quarter-finals at Wimbledon that year, and lost only in five sets to the eventual champion.

The next Indo-English cricket encounter, in 1976-77, compounded the humiliation: This time the English beat us at home, something they hadn't done since 1934. Skipper Bedi's intemperate accusations over John Lever's allegedly Vaseline greased seam success could not take away from the fact that India was completely outplayed in all departments of the game.

A gradual improvement occurred, though, when India made a four Test tour of England in 1979. I was living in Geneva at the time, and drove a thousand kilometres to Lord's, suffering a broken windscreen en route, only to find so much rain at the Mecca of cricket that little boys were floating paper boats at long leg. We lost the series, though Vengsarkar and Viswanath fought back for a memorable draw at Lord's. But the Indian side's valiant attempt in the last Test, again at the blessed Oval, to chase 438 for victory with Gavaskar leading the way with an extraordinary 221 restored national cricketing pride.

Yet India remained at the losing end in the series, a trend confirmed in the one off "Jubilee Test" of 1980 in Bombay, when 'That Man' Botham, with 13 wickets and a century, single handedly destroyed Viswanath's brief stint of captaincy. Revenge came in 1981-82, a five Test series clinched by India's victory in the first Test, all the others remaining drawn.

But there was little joy in that series, despite memorable knocks from Gavaskar and Kapil Dev, the emergence of Ravi Shastri and a record day long partnership between Viswanath and Yashpal Sharma.

For the good spirit of the '60s, already considerably strained by the Vaseline affair in the '70s (and developments that weren't cricket this was the time when British immigration officers were conducting "virginity tests" for Indian women deplaning at Heathrow), broke down completely in the '80s.

The English team, encouraged and undermined by the simple minded exaggerations of British tabloid journalists, became obsessed with the deficiencies, real and imagined, of the Indian umpiring, peevishly refusing to give credit where it was due and blaming their failures on everyone's mistakes but their own.

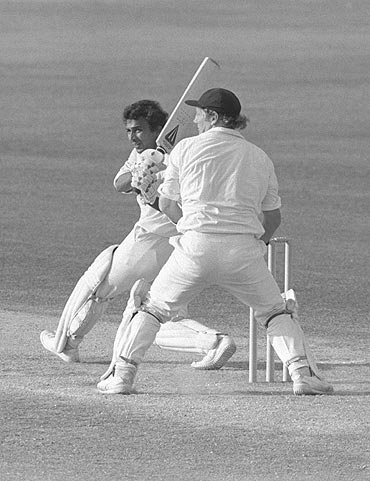

India discovered the magical Kapil and Azhar against the English

Image: Kapil Dev in action against England in 1982The bad blood continued during India's return visit in 1982, when a furore over umpire David Constant (whom Gavaskar had earlier described as "constant in his support of England") proved that two can play at finger pointing.

That series was, however, memorable for other reasons. England won, Botham was irresistible and Gavaskar injured in the decisive encounter but two Indians gladdened the hearts of their compatriots: Kapil Dev and Sandeep Patil. It had seemed before 1982 that the day of the exuberant and erratic. Indian genius was over; that the likes of Kunderan and Hanumant Singh had given way to the Gavaskar/Vengsarkar/Shastri school of cricket as an exercise in attrition.

But Kapil, with three brilliant innings (including one of 97 more glorious than many a century) and Patil, with a scintillating 127 that included 24 blistering runs off a Bob Willis over, proved that Indian cricket still had that magic spirit in it that had captivated this seven year old boy two decades earlier.

The next series in 1984-85 nearly called off as England panicked when the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was followed, in grim coincidence, by the gunning down of a British consul in an unrelated incident proved anti-climactic, from an Indian point of view.

After winning the first Test in Bombay with a bright and positive display, spearheaded by centuries from Shastri and Kirmani and six wickets in each innings from the little leg spinner Sivaramakrishnan, India let the initiative slip by surrendering abjectly on the last afternoon in Delhi and then gutlessly reducing the Calcutta contest to a meandering draw.

The series went out of India's hands for good in Madras, where Gatting finally came of age as a Test batsman and Fowler scored a double century in what became, ironically, one of his last Test innings. But the great Indian discovery of the winter was a lithe young batsman named Mohammed Azharuddin, who became the first player in the world to score centuries in each of his first three Test matches.

The 1990s saw the tenacity of young Tendulkar

Image: Sachin Tendulkar on the 1990 tour of EnglandRevenge this time was swift. Under a more positive captain, Kapil Dev, India crushed England at home in the summer of 1986, with Dilip Vengsarkar scoring his third successive century in Lord's Tests, a world record.

With the ball, India's Roger Michael Humphrey Binny, a descendant of Scot planters, bowled more like an English medium pacer than the medium pacers selected by England. There was conspicuously less talk of umpires when England dropped its beleaguered captain, David Gower, and replaced him by Mike Gatting, who in turn promptly lost his first Test in charge. The quality of the Indian tourists was self evident.

The sides would have been better balanced when they were next due to meet, in India in 1988-89. India, weakened by Gavaskar's retirement and chronic selectorial whimsy, might have been the crucible in which the England team of the '90s could have been forged. But apartheid, which had been a nasty undercurrent two tours earlier, now became a whirlpool, sucking the tour into the void.

The South African connections of eight English tourists proved unacceptable to the Indian government, and with neither Board proving particularly adept at compromise, the tour was cancelled.

The fiasco at last brought about a worthwhile agreement at the International Cricket Conference on the vexed subject of sanctions against those who give aid and comfort to institutionalised racism.

But the price was paid by the followers of India's cricketing encounters with England, for this was the only tour cancelled as a result of apartheid that did not involve a South African team.

The summer of 1990 provided an opportunity to heal the wound. Developments in both the cricketing and the political fields made the apartheid issue look ever more distant and irrelevant. Both countries were beginning the process of shaping their teams for the nineties; India were the bolder of the two, picking a touring team with only two players older than 30, under a resurgent new captain, Mohammed Azharuddin.

Though India could not manage a win, three magical innings from the skipper, and two of courage and tenacity by the precocious Tendulkar, offset the triumph of the seemingly invincible Gooch and offered hope that the rematch of 1992-93 would be worth waiting for.

Ganguly's gesture: Overturning of the old order

Image: Sourav Ganguly on the Lord's balconyWhen the Indians returned the visit in 1996, Ganguly (with centuries in his first two Tests) and Dravid began their illustrious careers with panache, and though the series was still lost 0-1 with two Tests drawn, the Indians demonstrated their quality with a whitewash in the ODIs.

England was beginning a slump that saw further defeats in India (1-0 in 2001-02 and 2008-09) and at home (0-1 in 2007); despite drawing the 2002 and 2006-07 series 1-1, England never quite looked as if they had the full measure of the Indians, with the spin of Kumble and the left-arm pace and swing of Zaheer adding to the batting mastery repeatedly demonstrated by the likes of Tendulkar, Dravid, Sehwag and Laxman. Indian dominance was underscored in their merciless routing of England in a series of one-day encounters over the last decade.

The iconic image of the India-England cricketing relationship of the last decade must be that of the victorious visiting captain, Sourav Ganguly, stripping off his shirt and waving it above his head on the Lord's balcony. Lord's is a pavilion from which many have been turned away for not sporting a jacket and tie; Ganguly's brash gesture seemed an act not just of defiance but of revolt against convention, an overturning of the old order.

In parallel, Britain has been paying heed to India's new global importance, with a succession of political leaders paying visits to New Delhi. When David Cameron was elected leader of the Conservative Party, the first country he visited to burnish his hitherto scant foreign policy credentials was India; when he became prime minister, he did the same, bringing one of the largest foreign delegations ever seen in New Delhi. The days when Englishmen -- politicians or cricketers -- declined to tour India have long since disappeared; what was once the jewel in the imperial crown glitters even more alluringly as the world's second-fastest growing major economy.

The Indian side that takes on England in the summer of 2011 expects victory

Image: Mahendra Singh Dhoni and Andrew Strauss at Lord's, ahead of the 2011 battle for supremacyThe team's gigantic fan base has produced players capable of inspiring millions, now led by a charismatic skipper, Dhoni, a latter-day improved version of Kunderan, and have climbed to the top position in the world Test rankings. Indians have become accustomed to winning; defeat is increasingly an anomaly. The Indian side that takes on England in the summer of 2011 expects victory.

But England has been rebuilding successfully, economically as well as in cricketing terms. They have a recent record of success and a settled roster of batsmen and bowlers who combine reliability with talent. India would be unwise to take anything for granted, especially in English conditions.

The cricketing relationship of the two countries has evolved parallel to the political: Memories of colonial dominance have faded, there is more open give and take, both sides are more used to one another and more accepting of the shifting balance of fortunes between them. It should make for an absorbing contest -- a contest between equals.

Comment

article