| « Back to article | Print this article |

Tiger Pataudi was the Great Seducer of his time

Ayaz Memon salutes Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi, who passed into the ages on Thursday.

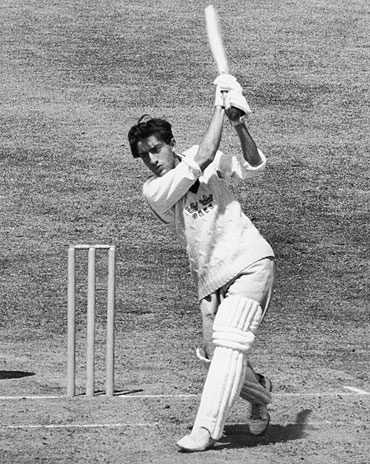

For those of my vintage -- growing up in the 1960s -- Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi was every boy's dream: dashing batsman, brilliant fielder and attacking captain. He was not just a cricketer, but also a Nawab and style icon with his neatly manicured hair, natty dress sense and the rakish tilt at which he wore his cap. Above all, he was a lady killer, which for most boys was the clincher. Women of all ages loved him.

- Share your favourite 'Tiger' Pataudi memory

If Sachin Tendulkar is the Pied Piper of contemporary cricket, Tiger Pataudi was the Great Seducer of his time. He was a superstar in the truest sense of the term. He commanded attention and adulation across the length and breadth of this country and the entire cricket world.

In sheer decibel levels, Tendulkar of course stands heads and shoulders above all else. But it is a different world now from the time Pataudi played cricket when newspapers were fewer and television almost non-existent. The aura around him grew from lore and by word of mouth: because of his royal lineage, the astonishing fact of playing at this level with one eye and of course the exciting quality of his cricket.

All these combined to create a super-hero of sorts. People would flock to see him just make an appearance at nets practice; if only to discuss the length of his hair, his regal carriage or indeed whether he would hit a six on that day. When it wasn't his attacking brand of cricket, it was his dalliance, most of them imaginary, with glamorous ladies that hogged dining table conversation.Pataudi was a rousing success on the Australian tour in 1967

Tiger Pataudi was the big hero of the first Test match I ever saw -- when India beat Australia by two wickets at the Cricket Club of India in 1964 scoring a vital half-century and leading -- as I understood from the knowledgeable then -- with elan and aggression. He had a penchant for the lofted shot, and the crowd would go into raptures every time he stepped down the track.

He was the favourite of the cheering crowds after the win (a photograph of Pataudi and some players standing on the CCI balcony adorns one of the club's walls), though when I reminded him of that moment last year he said that the crowds were probably rooting more for the bowlers, not for him.

Like countless people before and after, I was bowled lock, stock and barrel by Pataudi's charisma but it was only in subsequent years that one really understood his true greatness in playing with the most serious disability one can imagine in competitive, international sport: that of having only 'usable' eye.

I recall waking up early to listen to Alan McGilvray, Lindsay Hassett etc on Radio Australia singing paeans of praise to Pataudi's courage and panache on India's tour of Australia in 1967. The series was lost 0-4, but Pataudi was a rousing success on the hard, bouncy pitches Down Under. The fact that he played two of his three Tests with a leg injury made his efforts heroic and Sir Don Bradman was to say that he would have been proud to play some of the strokes Pataudi did.Pataudi's is a saga of heroic proportions

Purely from the sporting aspect, Pataudi's is a saga of heroic proportions. A car accident had caused him the loss of his right eye when only 20. This would have snuffed out the ambition and resilience of lesser men, but Tiger took on the challenge to overcome the handicap and play the sport he loved most. (For the record, he was also a terrific hockey and squash player).

The loss of one eye would have been unnerving. He saw most things double and only by trial and error at nets did he come to the conclusion that of the two balls he saw while batting, the real one was the inner one! Before he could even come to terms with his new style of batsmanship -- which necessitated a change of stance from the orthodox to the more 'open' -- Pataudi was being asked to captain the Indian team in the most excruciating circumstances.

When Nari Contractor was felled by a Charlie Griffith bouncer on the 1962 tour of the West Indies, Pataudi was foisted as captain over all seniors. He was only 21 and the Indian dressing room, as can be imagined, but must have been engulfed in both apprehension and disgruntlement.

His first task was to win over the trust of his teammates. This he did by adopting a policy of being fair and by personal example. It is difficult to fault a captain willing to lead from the front despite having only one eye. Even so, the Indian dressing room was a microcosm of Indian life in those days, divided strongly along regional and linguistic lines.

In his book, Tiger's Tale, Pataudi mentions why captaining the Indian team was perhaps the most difficult of all jobs simply because the players didn't even speak the same language and many of them carried their social prejudices into the dressing room. Bishen Singh Bedi, who was Pataudi's protege of sorts, has often said how the Nawab made them all believe they were Indians first, and to play as a team.

Gradually, all players were won over. Meanwhile, Pataudi had realized that the lack of genuine quick bowlers would always limit India's options unless he thought of a different strategy. He opted for the radical all-spin attack, and from this emerged the famed spin quartert of Bedi, Prasanna, Chandra and Venkat who were to bring great laurels to the country.

Birth and cricket royalty married cultural and film royalty

Support for the spinners came from superb close-in fielders like Abid Ali, Wadekar, Solkar who Pataudi had drafted into the side. He was a brilliant cover fieldsman himself, rated to be in the same class as the great South African Colin Bland. He was a sure catcher and had a flat, hard and fast throw that would thud into the wicket-keeper's gloves from even the deepest corners of the ground.

For almost 8 years, Pataudi's reign as captain was unquestioned. A spate of poor performances in the late 1960s especially against weaker teams like New Zealand and Sri Lanka (then not ICC-recognised) raised issues of indiscipline in the team and Vijay Merchant used his casting vote as chairman of the selection committee to depose him in 1970.

It was rumoured that Merchant and Pataudi had fallen out over issues of hierarchy: the former, it was said, wanted respect to be shown at all times; Pataudi, it was reported, said respect had to be earned not demanded. More likely, Merchant was emboldened by the winds of change sweeping the country in the wake of Indira Gandhi's fervor for nationalization.

One of the outcomes of this was taking away the privy purses and titles of Indian royalty. Overnight, Pataudi had not only lost his title and money, but also the Indian captaincy. He declined to tour the West Indies and England where the Indian team was to score historic wins under Ajit Wadekar.

By this time Pataudi had married Sharmila Tagore, then one of India's top film stars. And so birth and cricket royalty married cultural and film royalty. This was double star quality -- the romance between the film world and cricket is hardly new of course. Pataudi and Tagore were at the forefront of Bombay's glamorous set in the 1970s, and of Delhi once he moved to the capital.'I don't understand the game of administration and can't play it'

A brief foray into politics caused more grief than gain and he was back to cricket, and the national team in 1972-73, playing under Wadekar. In 1974-75 he was to be reinstated captain of the Indian team in a memorable series against Clive Lloyd's West Indies team but announced his retirement at the end of the last Test as his struggles against quick bowlers became more pronounced.

He had stints in the media as editor of a sports magazine and a TV commentator, and also as ICC match referee. Lamentably, he stayed away from becoming selector or getting into full-time administration with the BCCI. ''I don't understand that game and can't play it,'' he would say.

He did agree, though, to be on the governing council of the IPL for its first three years before resigning in 2010 when the post was made honorary. The parting of ways was unsavoury with Pataudi taking the BCCI to court for payment of his dues.

He cared deeply for Indian cricket, he was always skeptical of the Indian Board's overemphasis on financial rather than cricketing matters. At the inaugural Raj Singh Dungarpur Memorial Lecture last year in Delhi, he was to say that ''the ICC is the voice of cricket and the BCCI its invoice.''

As Indian cricket's most enduring star, Pataudi wore his fame lightly and would joke with people who addressed him as Nawab. ''I didn't know I was still called that,'' he would say. But for those who had watched him play and spent some time with him, the loss of the title was immaterial.

Even after he had become a commoner, he was a royal person in every which way.