Anindya Dutta relies on facts and figures rather than back stories to trace the history of Indian spin bowling, says Partha Basu.

Any author who sets out to write a book on sporting phenomena has to deal with a common and pernicious problem that afflicts the majority of his kind. It's entrapment, in a way.

Take cricket, for example; the easy way to fill out 300 or so pages is to draw on dates, events and any records you can ferret out and then let the statistics do your work for you.

Chances are your efforts will be applauded because there's a substantial readership out there that wants more of the hard points and rather less of the back stories.

There are, of course, the few who believe that the cutting edge of any noteworthy achievement resides in the circumstances that led up to it, more so the apparent adversities that had to be overcome.

Famed champion Lance Armstrong's remarkable run of Tour de France titles makes for great knowledge about Armstrong's superior cycling skills, but in the context of his cancer survival and his later admissions of drug delinquencies, his life's work takes on a coloration that statistics, however unique they are, can't underpin.

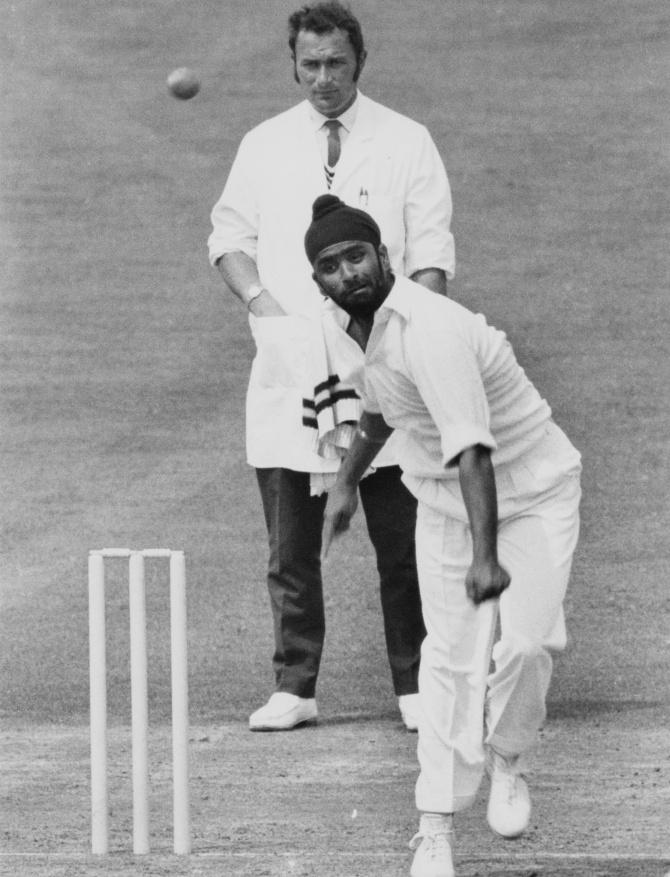

Therefore, as far as Wizards is concerned, did we not require Anindya Dutta to do more than make only brief references to what made Bhagwat Chandrasekhar the most explosive fourth of India's famed spin quartet?

For instance, what made him so lethal?

Was it the fact that his polio-affected bowling arm released the ball in the most unpredictable manner?

Or how much he relied on the predatory instincts of a Solkar at forward short leg and a Venkataraghavan at gully to threaten and then finish off the batsman?

And how exactly did this socially average youngster, struggling to come to terms with his disability, leave all that behind him and become the world's best leg spinner of his time?

Talking of leg spinners, Gideon Haigh, arguably the best cricket writer there is, writing incisively about the world's most successful leggie, deconstructs the Shane Warne ethos over a major part of his book to tell us how Warne the spinner developed the lethal attitudes of a fast bowler.

The point in all of this being that too many sums and summaries, without much attention given to the back stories that more often than not shaped the person, can turn a good sports read into a Wikipedia page.

Somewhere in the book I read this analysis of Bishan Singh Bedi's magic by Suresh Menon, a former editor of Wisden: '... Bedi could pitch six balls on the same spot and do different things, or pitch them at different points and make them do the same thing.'

'Few understood better than Bedi the separate role played by the fingers, the palm, the arm, the shoulder, the hips, the legs and the toes. He could alter the position of one of them at the top of his bowling mark and change the delivery.'

How's that for insight?

It's not that Dutta is shy of analyses. In fact amongst the best parts of this long book belong to where he examines the young captain Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi's SWOT analysis that led to the ascendency of India's spin department over a weak, non-existent pace attack through the seventies.

Dutta calls it Pataudi's Blue Ocean Strategy, a banker's term he explains, which means finding and then using your strengths in situations that are adverse to you.

Fast forward a decade or so; though our pace attack is now just about the best in the world, our spinners continue to afford their captain great winning options; he labels this as the young Nawab's well-formulated gift to our cricketing climate.

Dutta adds that Pataudi's other contribution to India's cricketing matters was a resolute moving away from the regionalism that defined the Board's policies (he presents numerous examples of this ridiculous mindset) towards a strong sense of unity in the team's Indian-ness.

Decades later, he explains, a later Nawab, this time of Kolkata, established himself as a worthy successor to the Pataudi royal.

Dutta has over two decades of international banking under his belt and is very capable of sorting and collating data.

His book further reveals his banker's genes in the manner in which he works his way methodically past every Indian spinner you've heard of and many of whom you haven't, from Palwankar Baloo (1906) to Yuzvendra Chahal (2016), a national chess player.

At the end of it, the book, heavy with facts and figures concerning people and tours and wickets and averages and matches and careers and wins and losses, tends to become a bit tiresome as Dutta reaches for data overkill. However, he is a committed writer and let's hope his next book is more about back stories.

© 2025

© 2025