'When he cover drives, who the hell cares about where the ball pitched? I only know that he seems to move so lazily and has all the time in the world to make incredibly elegant and powerful strokes. He has something that other don't...'

'When he cover drives, who the hell cares about where the ball pitched? I only know that he seems to move so lazily and has all the time in the world to make incredibly elegant and powerful strokes. He has something that other don't...'

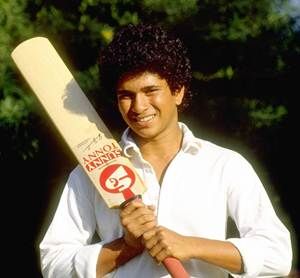

As the Master announces his retirement from the game after his 200th Test, we republish another Master -- Varsha Bhosle -- on Sachin Tendulkar.

Like every Indian, I come from a cricket-crazy family. In childhood, I enjoyed the trappings of the game: The tiger-like lope of Wesley Hall, the robust sixers of Gary Sobers, the knotted kerchief of Pataudi, the graceful sweeps of Ajit Wadekar, the dash of Salim Durrani, the rumbling of Brabourne Stadium, the method in the madness of maidan cricket. I was reared on it all.

No, I didn't really understand how and why the ball landed where it did, and how batsmen could anticipate the swing; nor could I fathom the lbw. Thus, when BalMama muttered "gela re gela" even before the ball would begin its trajectory from the crease, to me, the result was unexpected and exciting: a little ignorance needn't always be a bad thing. For me, it still is only a batsman's game.

At home, the cricket season heralded a mood of philosophising on the similarities in cricket and music. Prasanna bowled like a murki; the late cut (my favourite, incidentally) was a puncham in Bageshri; a body-line attack was dhrupad-dhamaar and Real Men faced it chest-on, etc, etc. Most vitally, a committed move by a batsman was akin to the note that left a singer's throat: There was no chance to convert it. 'Twas very intriguing.

Of my three early passions, music and films reached happy maturity. The third, I betrayed -- by having an affair with Italian soccer the day my brothers and cousins started playing galli- cricket in earnest. I was so saturated with silly points and straight elbows, that I withdrew altogether. When BalMama began his seasonal raga of cricket and music, I sneered and took a walk.

One day, I went to some god-forsaken maidan to pick up my friend, your friendly sports columnist Hemant Kenkre, who, of course, was still bonding with his team-mates in the tent. The pavement where I waited was crowded with very vocally appreciative men who obviously had nothing better to do than loiter around the ground in the summer heat. I wondered what the fuss was about, and nudged my way through the throng...

A skinny little thing was performing a taandav with the bat, ball flying here, there and everywhere. Not bad, I thought, nice fluidity of movement. On the way home, I mentioned it to Hemant...

"That's Tendlya. Kaay ahe to! (what a guy!). Just wait for a year or two; he can do anything with the bat against any attack. His jigar...." I promptly tuned off for the rest of the drive.

Barely a year later, the usual coterie of maniacs, but excluding Hemant, was watching cricket on the idiot-box. As I was passing by, my brother said, "Wait a minute and watch this guy play." "Humph", said I, but was pressured to spare the minute nonetheless. He's darn good, I thought, where've I seen this guy before? "That's Sachin, he's new. Aplya Bombay cha ahe." He reminds me of Vishy, I said.

"Hah! Kaay ahe to!. Just wait for 6 months; he can do anything with the bat against any attack. His jigar...." I promptly returned to my room.

A month later, I went to the Cricket Club of India -- only for lunch, mind you -- and had to endure a club game. Those off the field, including Hemant, were occupied in mature activities like swishing off caps from each others's heads, hiding somebody's pads, etc. A bit away from the frolics, a skinny little thing with a mop of curly hair sat staring intently at the players on the pitch. Looks familiar, I thought. And then, he went on the field.

There was a slight change among the revellers: Some actually looked towards the batsmen, and Hemant sat down beside me. Nothing romantic, I assure you; it was a ploy to be left alone by his mates: They had already learned to avoid me in the club...

It was a game of no import, just buddies avoiding a Sunday at home. But Curly-top played like India was depending upon him. That was when I came back to cricket after years and years in the soccer wilderness. I came home to cricket on the very ground that acquainted me with it. "Hemant, who's this kid? He's fan-tas-tic!"

"That's apla Tendlya. Don't you remember watching him on the maidan? Just wait for 6...."

"Oh shut up! Is this some male initiation thing?"

"....months more. He can do anything with the bat against any attack. His jigar...."

"Please, listen just this once: I do *not* need your pitch. This kid is a Star, capital 'S', and I don't want to wait for 6 months more. Now, introduce me to him." That's how I met Sachin Tendulkar.

Years passed; Sachin dashed from League to Ranji. In the interim, I once again took to watching cricket, and took over the ad campaign for my sister-in-law's tailoring business. We had celebrities from different field endorsing gents clothing, and after Jackie Shroff, Jagjit Singh and Zakir Hussain, it was the turn of a sportsman -- 'man' being the operative word.

Years passed; Sachin dashed from League to Ranji. In the interim, I once again took to watching cricket, and took over the ad campaign for my sister-in-law's tailoring business. We had celebrities from different field endorsing gents clothing, and after Jackie Shroff, Jagjit Singh and Zakir Hussain, it was the turn of a sportsman -- 'man' being the operative word.

The obvious names: Pataudi, Gavaskar, Ferreira, Kapil Dev and Vengsarkar, were put forth by all those whose business it was not. I knew who I wanted -- the hitch was that, technically, Sachin was still a boy. All the same, I sent my reluctant emissary to do the ground work: It was Hemant's job to inquire if he was agreeable to my proposal, and if so, how much would he charge.

Sports had suddenly become big business, and cricketers locked horns with film stars in terms of popularity. Inspired by the financial acumen of the legendary Gavaskar, they were no longer the gullible exploited of yesteryears. I heard that even the accepting of dinners had a price. It was pure commerce, and I'm all for it.

However (income-tax authorities please note), Sachin did the ad for love and fresh air. He was right at the top, everybody's darling; there was a line of such offers waiting at his door, and he did the ad for no reason I know for sure. The cynic in me immediately suspected the worst: Was he planning to produce a movie, and thus needed to oblige my family...?

An under-20, and a cricketer to boot -- and not measuring and weighing everything against a gold brick? Unthinkable! Well, it's been 8 years since then, and he hasn't even met my brother, leave alone my mother. Nor does he plan to break into films or music. I guess that he did the ad only because of some tenuous links with his erstwhile team-mate. That's the mettle of the man.

When I was asked to write on him, I was stumped. What could I say that hasn't been appearing in the papers every day? Why would I pry into his personal life? How could I describe what I see in his play? You can't pin down a symphony, can you? Then there are those who'll question my qualifications to comment on his game...

Music has had the last laugh -- I can explain my qualifications only with a musical analogy: I once witnessed Mehdi Hassan's private mehfil where not a soul in the audience could be assessed as being knowledgeable in or respectful of music. While he sang his heart out, the philistines were slopping whiskey and jabbering: it was a collection of the tone-deaf. Khansahab looked miserable as he began the last ghazal...

It was one of those rare moments when the singer's sur, for no apparent reason, fuses so perfectly with the vibrations of the tanpura, that the cognoscenti actually get gooseflesh. More extraordinary was that Khansahab continued in that vein. The audience gradually grew silent... After the concert, I heard one of them slur, "Woh last gana kuchh ajeeb tha." He didn't know how or why it sounded different, but his sixth sense had felt it. He had *listened*; they all had.

I have come across this reaction many times, and at different concerts. Sometimes, the magic lasts a few minutes, at luckier times, an hour. The clincher is that only a handful of artistes have the mastery to induce it. Perfection is a powerful force -- it demands and receives attention without the aid of knowledge or experience. It hypnotises...

And so is it with Sachin. When he cover drives, who the hell cares about where the ball pitched? I only know that he seems to move so lazily and has all the time in the world to make incredibly elegant and powerful strokes. He has something that other don't -- call it star-quality, if you like. Besides, he can do anything with the bat against any attack. His jigar....

The incomparable Varsha Bhosle sadly passed into the ages last year.

Photographs: Getty Images and Ben Radford/Allsport

© 2025

© 2025