The number of poor people travelling by train has followed a similar trend since 2011.

Subhomoy Bhattacharjee reports:

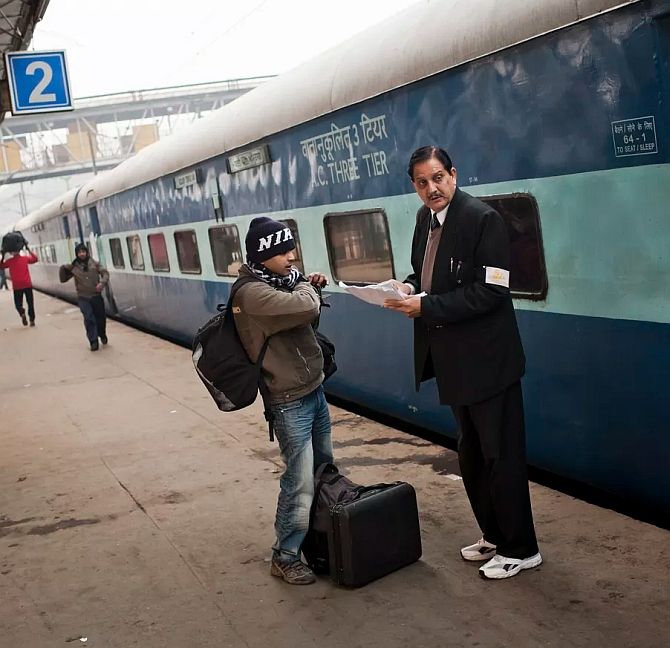

Train travel dipped massively among the poorest in December last year.

The Indian Railways data shows there was a fall of nearly 7% in the number of those who travelled unreserved in trains in December 2016.

But before demonetisation can be blamed, the official data needs to be looked at.

There was a larger fall among train passengers of this class two years ago too.

In December 2014, the number of poor people who travelled by train went down 8.5%, compared with the year before.

The same trend was seen in December 2013.

Of the past six years (2011 to 2016) of railway ticket sales data analysed, not a single month stands out as an outlier.

In other words, there has been no change in the travel habits of the poor, post demonetisation.

This is quite against the assorted anecdotal evidence -- that has mounted since the note ban was announced on November 8 -- of a spurt in distress travel, from urban to rural areas.

But try whichever way to splice the passenger data, it shows up no evidence of any change in the travelling pattern among the poor in the two months since November 8.

The Indian Railways keeps separate data on passenger tickets that are bought through its reservation windows or online, from those that are bought as unreserved tickets.

The former bunch is known as PRS (passenger reservation system) and the latter as non-PRS.

This means, when you buy a ticket for a confirmed berth ranging from a premier first class air-conditioned (AC) coach to a non-AC sleeper coach, the booking is shown as part of the PRS statistics.

The snaking line of poor at railway stations in front of the booking counters, that open just a couple of hours before each train leaves, form the non-PRS data.

Post demonetisation, a massive jump in the number of non-PRS tickets bought was expected.

It was reckoned to happen as hordes of poor people employed as daily labourers or on short-term contract would lose their jobs in towns as cash ran dry.

It was speculated that once they lose their jobs, these workers would have to leave for their homes in rural or in semi-urban centres.

In this analysis it is impossible to figure out if such job loss on a large scale has happened. But assuming it has happened, till the end of December 2016, a lot of them have not boarded trains to return to their homes.

This is, of course, discounting the possibility that a large number of them would have travelled ticketless, which is quite an absurd presumption.

Since bus travel over long distances is difficult, it is also fair to discount it as the preferred mode of travel.

And given that unreserved train tickets are cheaper over long distances, the returning workers would be expected to avail this option than a bus ride back home.

Examining the data for October since 2011, one is able to get a better insight of the developments.

Travel soars in October every year, which is not surprising, as it is the month of festivals in the country.

During this month, most workers either return home or join back work after the festivities. So each year, there is a spike in both -- PRS and non-PRS -- types of travellers.

Once the festive season is over, the trains become less crowded in November and December. This trend can be seen every year.

The difference between passengers boarding trains in October and December is sizeable.

The pattern should have been altered with demonetisation, but even in 2016, the difference is similar to that in the past five years.

Another hypothesis is that workers in the informal sector have not travelled out of the industrial or service centres after the note ban was announced.

This could have happened as they might have run out of cash to buy train tickets.

This hypothesis doesn't hold, as the dip in train travel among the poor had begun before 2016.

For example, lower-class tickets were sold less in November 2016, just as they were in 2014 and 2013.

Tracing back the data to October for 2011 to 2016, show a dip in ticket sales in four of those years.

Since the dip was seen in four successive years since 2013, the data possibly indicate a crimp in surplus income among the poor that predates demonetisation.

Another interesting trend can be seen in the data analysed. In November 2016, the number of tickets bought from the PRS window had risen sharply.

Would a percentage of the workers thrown out of jobs be located here?

This, too, is unlikely in case of a cash crunch.

The rise can't be explained if sale of unreserved tickets had gone down.

It is even more unusual, since in four of the six years, there has been a similar robust year-on-year rise in sales of reserved tickets in November.

And after logging such a sharp rise, there is no reason why the growth should turn so anaemic in December 2016, since the shortage of cash and its consequences were still playing out.

The implication of the flat trend in train passenger movements shows there is little evidence of mass scale desertion by workers from towns, after demonetisation via the railways.

Of course, the reasons why they chose to stay back do not emerge from these numbers; it has to be investigated separately.

Photograph: Daniel Berehulak/Getty Images