The e-commerce story in India has begun to look up, says Aparna Kalra.

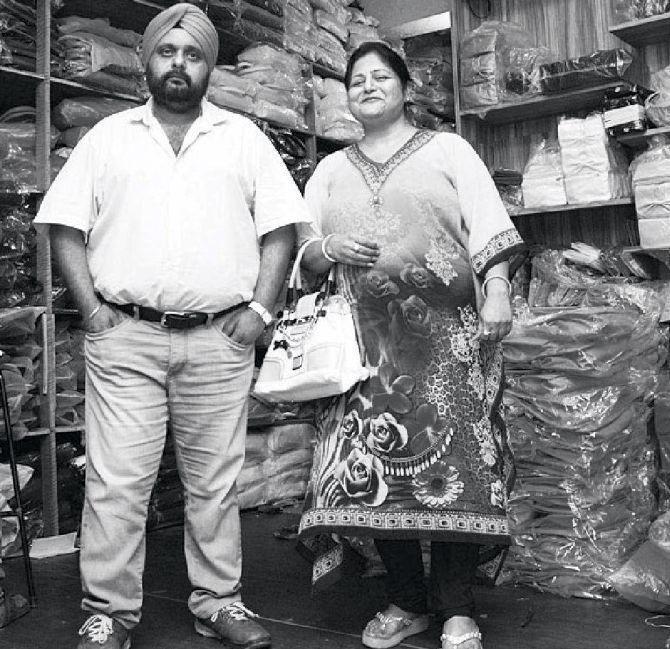

Navdeep Narang and wife Sanjeet are in their rabbit warren of an office under the Naraina flyover on the Ring Road in New Delhi.

A window shows the heads and backs of workers in vests, it is hot and humid and the small space with racks and racks of merchandise does not have air-conditioning.

The workers are packing handbags and purses designed for women into packets marked Flipkart, Jabong, Amazon and Snapdeal, four e-commerce websites on which Narang sells his brand.

The brand, butterfliesbag, hit record sales in the week to meet demand for Raksha Bandhan, a Hindu festival that celebrates the love and duty between brothers and sisters.

Meanwhile, in Greater Noida, a husband-wife team of the Yadavs, Devendra Kumar and Swati Singh, arrange for shipments to arrive from Moradabad, where they have a manufacturing unit.

The couriers of Flipkart, Amazon and Snapdeal pick these packets from Greater Noida by ten in the morning.

The Yadavs are e-tailing their brand, crunchyfashion, a range of costume jewellery and accessories for women.

They chose Moradabad for making their goods as it is the hub of brassware in India; labour here is cheap and steadfast.

The Yadavs, both born in Uttar Pradesh, and the Narangs, who belong to Agra and Delhi, form a tribe who have launched their own brands and boosted their sales from online orders from small towns and cities.

In July, Flipkart raised $1 billion in equity, followed by Amazon saying it would plough $2 billion in India.

From ordinary man to sir

Indian e-commerce began with sites such as Flipkart building inventory and losses, but underwent a shift in two years by moving to the marketplace model, where they invite others to list and sell their wares.

This was the beginning of an exhilarating ride for the Narangs. "I remember when I used to sit outside Liberty office waiting for them to call me in. And now people call me sir and ask for permission to enter my office," says Navdeep Narang, who supplied accessories to Liberty, an Indian brand of shoes, while dreaming of owning his own brand.

That dream materialised when he got a call from Jabong in 2012, asking him to list a few pieces.

"We had not even heard of it," said Sanjeet. She designs the bags while Navdeep takes care of the inventory management and dispatch.

At the time of the first listing, the Narangs had made a few handbags for their brand. They lay around as inventory as Navdeep could not take out time to invest in his own brand.

"I thought I will put them in shops, maybe one day have a shop of my own. This Jabong lady, a dear friend from earlier, said, 'Send three or four items of each bag, I will just list these online'," said Navdeep.

"In five days, she called to say all bags had been sold. I had a replacement order, and an order to send more bags. That's when I realised there was a spark."

Soon, butterfliesbag started e-tailing on Snapdeal, followed by Flipkart in 2013. As orders flew in, the Narangs added floors and storage space in Naraina.

"I was previously on the first floor, then this place got vacated, then I added the dispatch," said Narang, pointing in all directions.

He clicks on a remote, and a closed-circuit TV shows several work areas. In one room, workers are checking each product to see if it is in perfect shape to be shipped.

Narang terms this QC or quality control. In another area, a tiny butterfly is being attached to each bag to show brand signature.

The bags are not made in Naraina; their manufacturing is done in places such as Mangolpuri and Tri Nagar.

Sanjeet says she has expanded the colour palette of her brand to include turquoise, lime green, and yellow. She has also put out more combinations of colours.

Earlier this year, the Narangs' faced a tough time, losing Sanjeet's father. A day after his father-in-law's last rites, Navdeep got a call from US-based giant Amazon to list his products on their website.

"It was a big thing. I didn't call them, they called me," said Navdeep.

Marketplaces benefit several thousand vendors listed on them by providing them with an additional sales channel, says a July 2014 study by Technopak.

"Smaller vendors gain the most as the marketplace gives them a platform through which to set up their online business with minimal investment and risk as such supporting functions like marketing, logistics and customer support are managed by the e-tailer," said the July study, which pegs the e-commerce market in India at $2.3 billion or 0.4 per cent of total retail, to reach 3 per cent of it by 2020.

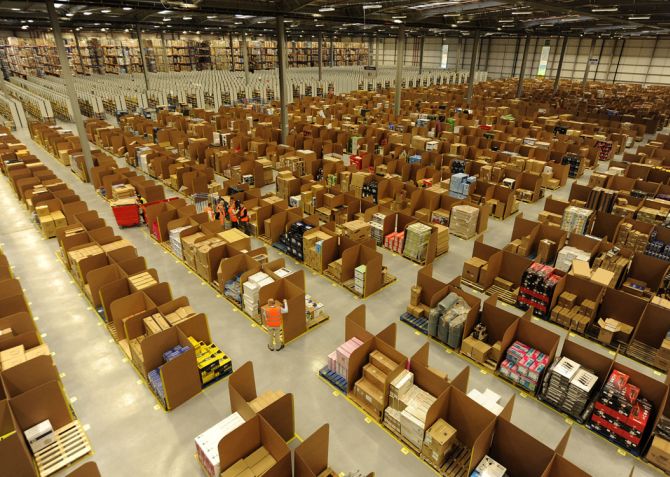

The e-tailing biggies such as Flipkart and Amazon charge a commission from vendors for each sale. Amazon said it charges for storage if a vendor uses that facility. Both Flipkart and Amazon are trying to invest in warehousing.

One of the reasons could be that quality of vendors, who are still trying to decipher the online market, is an area of concern, says Teknopak, as they lack adequate infrastructure, inventory management and packaging skills.

The Narangs' and Yadavs' journey bears out how small businessmen are coping with the e-commerce boom.

Hands on

Like any other small business owner, Devendra and Swati are available for their business, says Devendra, 24X7, through video conferencing or Skype, used to keep tabs on the Moradabad manufacturing unit or to answer customer queries, or for showcasing their products.

Navdeep personally supervises his workers, and says he can work into the night on days when his brand gets heavy orders, such as on festivals.

"It is do or die. And for me, it was do", said Navdeep. He now employs 100 people, some on per piece basis.

His latest employee, a young man in spectacles, is sitting with a laptop and is dedicated to increasing sales on Amazon by offering deals such as 50 per cent discount on all Butterflies bags; Amazon will bear half of the cost of this discount.

Navdeep says buying more storage space in crowded Delhi will be a problem. The Yadavs of cruncyfashion.com say they plan to solve this problem by opening small warehouses in small cities.

No bricks-and-mortar dreams

On the weekend prior to Rakhi, the Narangs' hit their biggest sales day, selling 1,500 pieces in a single day. They no longer dream about opening shops, they know the growth is online.

"We still cannot believe we are part of it, the (e-commerce) success. For me its like a fairytale," said Sanjeet.

Though the Narangs' themselves don't shop online much - Sanjeet sometimes looks for perfume deals - their 13-year-old son does.

His most recent purchase was a can of white spray paint with which he offered to "set right" his father's white car.

Navdeep declined the solicitous offer, leading the teen to paint the name plates of his own home, besides those of the neighbours on the top two floors.

The Narangs' won't be around the house much, not because of the repercussions of the spray paint incident, but because they have bought another house next door and are getting it done by an architect. The e-commerce story has begun to look up for them.

© 2025

© 2025