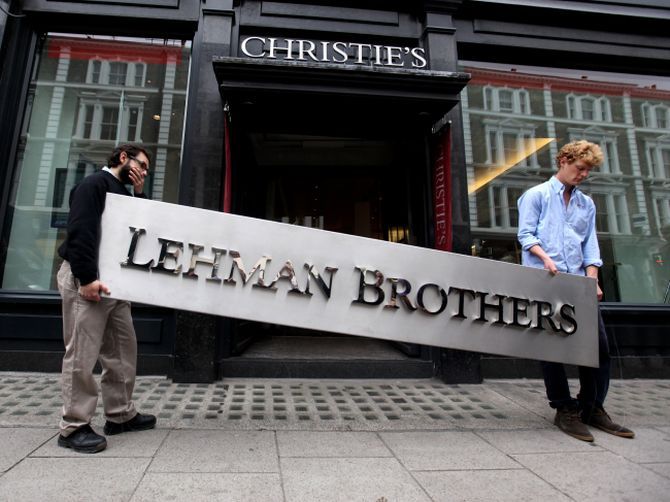

The 2008 financial crisis set off by the crash of Lehman Brothers in the US pushed back global growth, which declined from a high of 5.6 per cent in 2007 to 3 per cent the next year and a negative 0.2 per cent in 2009.

While multiple accounts speak of fraud and criminality that contributed to bringing the world to the brink of financial ruin, the biggest failure is that hardly anybody of consequence saw the inside of a jail cell.

The system continues to have an incentive for banks to take risks as they believe the Fed will be there to bail them out if their bets go awry.

On the 10th anniversary of the global financial crisis, a multi-part series analyses the lessons learnt and those not learnt.

The fall of big-bulge investment bank Lehman Brothers and the global financial chaos that followed after defaults in subprime debt have had a major impact on the world economy and the financial system.

Regulators across the world, led by the US Federal Reserve (Fed), came out with bond-buying programmes, thereby supplying easy money and also made drastic cuts in interest rates.

In August 2007, the Fed’s benchmark interest rate stood at 5.25 per cent.

Today, despite seven rate hikes since December 2015, the rate is now 2 per cent.

In the UK, the rate is 0.75 per cent, down from 5.75 per cent a decade ago.

The European Central Bank’s benchmark rate is zero, compared to 4 per cent in 2007.

Low interest rates have helped those who have mortgages and other debts, but have been painful for savers.

The financial crisis pushed back global growth, which declined from a high of 5.6 per cent in 2007 to 3 per cent the next year and a negative 0.2 per cent in 2009.

After the crisis, a slew of banks shut shop or were acquired by other banks.

The US government stepped in to bail out mortgage companies Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and insurer AIG.

The domino effect was felt across the world, with governments in the UK, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Iceland also having to step in to save their financial institutions.

The human impact was significant -- while about half a million jobs were lost in financial services, the impact on construction and manufacturing was much higher as 8.8 million Americans were made redundant since the start of the financial crisis, according to the US department of treasury.

Workers were laid off elsewhere in the world too.

Soon after the Lehman collapse, the US government and the Fed got involved in saving banks that were “too big to fail” and would have taken the financial system down with them.

JPMorgan bought Bear Stearns, Bank of America acquired Merrill Lynch, and Warren Buffett invested in Goldman Sachs.

But some things never change.

A decade later, banks haven’t got smaller, though. A majority of assets are still concentrated with the 10 largest banks, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Also, a global deleveraging was expected after the crises, but debt levels today are higher than ever before.

According to the Bank for International Settlements, the world’s debt load has risen from around 200 per cent of gross domestic product in 2008 to 244 per cent by the end of 2017.

The McKinsey Global Institute, the research division of the consulting firm, noted that the non-financial corporations, governments, and households have added $72 trillion since 2007.

Even risky instruments, which contributed to the worsening of the crisis, becoming increasingly popular again, with stories emerging last year of the return of the synthetic collateralised debt obligations.

The markets, in which such instruments trade, are still opaque.

Fed chairman Janet Yellen talked about the lack of transparency in derivative markets in 2013 and global regulators, grappling with increasing transparency for derivative products, have sought comments through a consultative paper on governance arrangements for over-the-counter derivatives last month.

Some of the angst that the common man carries about the havoc the financial crisis wreaked on the world order may be justified.

While multiple accounts speak of fraud and criminality that contributed to bringing the world to the brink of financial ruin, the biggest failure is that hardly anybody of consequence saw the inside of a jail cell.

The system continues to have an incentive for banks to take risks as they believe the Fed will be there to bail them out if their bets go awry.

The list of financial regulations introduced since the crisis is long, forcing banks to hold more capital to cover potential losses, restricting speculative trading, and giving central banks more powers to supervise banks, including stress-testing lenders’ balance sheets against future crisis.

But now, the Donald Trump Administration wants to roll back restrictions under the Dodd-Frank Act.

In a blog post on 10 years of the global financial crisis, International Monetary Fund managing director Christine Lagarde sums up: “We have come a long way, but not far enough. The system is safer, but not safe enough. Growth has rebounded but is not shared enough.”

Lehman’s 2008 collapse wasn’t the only time that speculation led to a crisis, and nor would this be the last one.

The creation of the US Fed traces back to the Panic of 1907, which was triggered by the Heinze brothers’ failed attempt to corner shares in United Copper resulted in a bank run.

Since then, the Fed as a lender of last resort has stepped in regularly to avert crisis in the financial markets.

Experts also say that the global financial crisis led to rising inequality, populism, and protests such as Occupy Wall Street.

Even the protectionism path that Donald Trump is following has roots in the crisis.

Lagarde wrote, 'We are now facing new, post-crisis, fault lines -- from the potential roll-back of financial regulation, to the fallout from excessive inequality, to protectionism and inward-looking policies, to rising global imbalances.

'How we respond to these challenges will determine whether we have fully internalised the lessons from Lehman.

'In this sense, the true legacy of the crisis cannot be adequately assessed after 10 years -- because it is still being written,' she said.

Photograph: Andrew Winning/Reuters.

Next: Anatomy of the crisis

© 2025

© 2025