| « Back to article | Print this article |

Why metro rail may not solve India's traffic woes

Mobility is essential to city life. So how can we make getting around easier, better and more convenient for our cities?

What are the options, and what are their costs and impacts? How equitable is each? And finally, how sustainable is each option, in terms of economics, public health and the environment?

The answers to such questions offer a rational counterpoint to the metro mantra being chanted by city after Indian city, and now rising to a crescendo.

A sensible infrastructure solution is one that solves the problems (and does not create new ones), costs the least, benefits the largest number of people, does the least environmental and social damage, is reversible, and has the flexibility to adjust to changing needs in the future.

Of course, no solution is perfect. There are always trade-offs. But how do we weigh those trade-offs?

First we must thoroughly understand the problem and its context. Then we must decide on the criteria by which we judge how well the solution -- in this case, a metro system -- actually meets all the various requirements. Here are some points to address.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Why metro rail may not be the best answer to traffic woes

Non-motorised transport

Non-motorised transportation deserves closer attention.

Geetam Tiwari of the Transport Research and Injury Prevention Programme at IIT Delhi has estimated that, at peak hour, 30-70 per cent of all trips in our big cities are by foot or bicycle. (Related fact: most trips in Indian cities are also under 5 km, which is bicycling distance.)

People making these trips are 'captive users' -- they cannot afford even subsidised public transport and are forced to walk or cycle.

Therefore, a sustainable transportation policy would start by making mobility easier and safer for pedestrians and bicyclists (who together have the largest share of fatalities in road accidents).

Interestingly, this would benefit all road users. Those who use motorised transport, whether personal car, suburban train or city bus, also need to walk.

Encouraging walking and bicycling through design and policy makes ecological and social sense. Both have almost zero energy costs and emissions, result in very little pollution, and boost public health.

And, in case you hadn't already guessed, catering to pedestrians and cyclists will make our cities more beautiful.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Why metro rail may not be the best answer to traffic woes

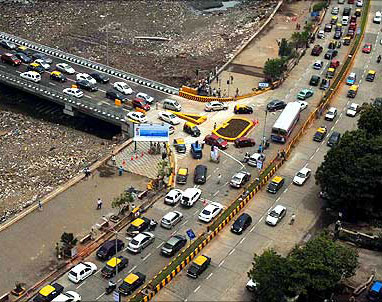

Bus kya?

Buses are perhaps the only public transport system already at work in most Indian cities. This is not surprising, since buses require much smaller investments.

They are also more flexible in answering demand, and can reach every corner of a city.

The metro is a First World concept. But the bus rapid transit system (BRTS) is a concept innovated in a Third World city -- Curitiba in Brazil, where it has worked well.

The essential BRTS idea is dedicated bus lanes to which other vehicles have no or limited access. Ahmedabad has a 'closed' BRTS which has proved to be a success.

Planning on Ahmedabad's system began in 2005, and operations started in October 2009. The system is estimated to cost Rs 1,000 crore (Rs 10 billion) for the full 88 km. So far it has reached 35 km, with no cost overruns.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Why metro rail may not be the best answer to traffic woes

Today 85,000-90,000 passengers a day use its 41 buses, says Shivanand Swamy of the Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology, Ahmedabad, who helped design the system.

"BRTS is pertinent for India," says Vidyadhar Phatak, a former chief planner of the Mumbai Metropolitan Regional Development Authority, "but you cannot do it half-heartedly. There is always going to be a conflict between different conditions in the case of BRTS, but it can be addressed to arrive at the best resolution."

Phatak adds that car users in Indian cities with BRTS believe that buses are taking over their roadspace. When there is no bus in the bus lane, car drivers feel that roadspace is being wasted.

They don't recognise that a single bus carries as many people as a jamful of cars. "Unfortunately, in India people who benefit from a system like BRTS rarely raise their voice in its favour," he says.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Why metro rail may not be the best answer to traffic woes

Clear the road

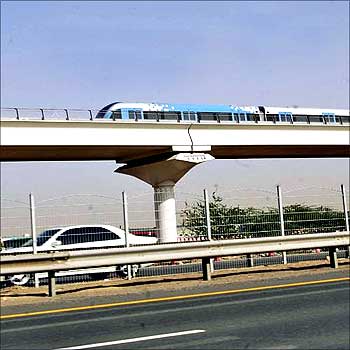

The chief attraction of a metro is that it is disengaged from the chaotic road situation.

"Metro projects are often promoted by saying that the roads are so congested, we have to go over or underground to get fast public transport," says Sujit Patwardhan of Parisar, a Pune NGO fighting for sensible urban policies.

"But this makes no sense. If there is a problem on the road, solve it, don't run away from it. People don't cause congestion on roads, cars do."

Patwardhan's argument forces us to consider an awkward possibility: that even after the huge expense on metros we might still be left with congested roads. After all, convincing evidence that car users will switch to the metro is thin (see slides 7 and 8). Unless, that is, we solve the road problem by curbing cars, since it is cars that eat up scarce public space on roads. If we can do that, we might even find that we never did need the metro!

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Why metro rail may not be the best answer to traffic woes

Metros and urban form

It is well known that a metro is many times more expensive than other public transit options. Its other costs are not so widely known, including damage to urban form and public space.

Urban form is no elite concern. It matters more to the poor pedestrian than to the rich in their cars. Our sense of comfort in a city depends on its legibility.

Can we make sense of our street networks, orient ourselves, remember places we are walking through? Do we feel psychologically comfortable in a space?

In Mumbai, for instance, flyovers built in the late 1990s have chopped up each of a wonderful sequence of garden roundabouts. Chopped up, these spaces fail to register fully.

The flyovers have mangled our experience of moving through. The looming concrete masses of the elevated sections of metro lines will do the same in many parts of cities like Mumbai.

Remember, most metro lines in cities outside Delhi are going to be elevated.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Why metro rail may not be the best answer to traffic woes

What is wrong with the metro idea?

In a report titled Mythologies, Metros & Future Urban Transport, Dinesh Mohan of IIT Delhi reviews the national and international literature on the question of which public transport system is appropriate for Indian cities, and arrives at a critique of the metro. Here is a summary of his arguments.

1. Metros do not carry the largest percentage of all trips in any city in the world. The largest shares are in cities that got public transport systems in the first half of the 20th century, when other options were not available. In such cities, like London, New York and Paris, the metro does not absorb more than 20 per cent of all trips. Tokyo and Hong Kong are exceptions. In Tokyo, 40 per cent of trips are on the metro; but car ownership is discouraged by limited parking and roadspace.

2. Metros only work well in cities that have large concentrations of jobs in central business districts. London, Paris and New York meet this condition. Indian cities, which generally have a polynucleated character and no single business district, do not.

3. A large population does not guarantee ridership. Shanghai compares with Mexico City but has just half the latter's ridership. The Delhi Metro Rail Corporation claims that any city with over 3 million people needs a metro. Density and the nature of spread of a city are, however, as relevant as the population.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Why metro rail may not be the best answer to traffic woes

4. It is not easy to wean car users away from their cars. It is difficult to beat the door-to-door travel time of a car, if you include time taken to reach the metro station, walk in the station and wait for a train.

5. A study of 210 transport infrastructure projects worldwide has shown that costs are significantly underestimated and benefits exaggerated. (This is generally true of big-ticket projects, because they benefit the officials who commission them as well as the consultants and contractors who execute them.) We can take consolation from this: we are not alone in our misery.

6. A properly designed BRTS does better on many criteria than any rail-based system.

The full report is available at www.iitd.ac.in/tripp

Whom should we emulate?

For models, let us look to America. No, not that America. In Curitiba, a small city in the South American nation of Brazil, was developed a BRT system that provided multiple benefits.

Along with greater access and economy, and lower environmental impact, came a better quality of public space.

Bogota, the capital of Colombia, has a BRTS as well as the longest pedestrian avenue in the world -- 18 km long. Quito, capital of Ecuador, also has a successful bus transit system.