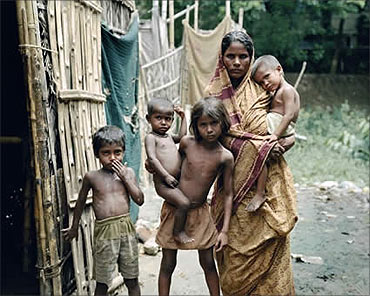

Photographs: Reuters M R Venkatesh

With just two words -- Garibi Hatao -- Indira Gandhi changed the fate of the 1971 elections.

In those heady days of socialism this slogan coined by the Congress party in the run-up to the parliamentary elections then captured the imagination of the electorate and, perhaps, the nation itself.

The then Opposition could neither counter this slogan with an effective plan nor at least by another imaginative slogan. Garibi Hatao, Indira Nahin, (remove poverty, not Indira Gandhi) was her short yet effective punch line. No wonder, Indira Gandhi swept that particular Lok Sabha election.

Since then several governments have been formed at the Centre. Several political formulations with diverse political ideologies have claimed to have been voted to power.

. . .

The fundamental flaw in our fight against poverty

Photographs: Reuters

Each one of them has vowed to tackle the menace of poverty. Yet, poverty continues to proliferate in India as government after government continues to be voted out.

In the interregnum, the government has constituted several committees and taskforces to tackle poverty. Earlier some blamed it on India's fixation with socialism. Now they blame it on the new economic policies of the government.

Yet others blame it on our genes. Whatever it be, we have failed to eliminate poverty.

Wiping away poverty in one stroke

Nevertheless, over the years India recorded robust GDP growth and a concomitant increase in per capita income (in spite of a burgeoning population).

. . .

The fundamental flaw in our fight against poverty

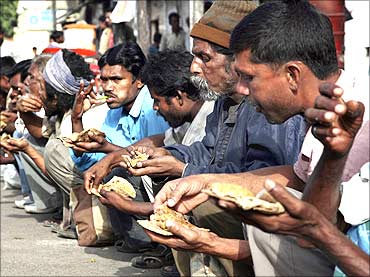

Photographs: Reuters

And despite all these positive developments at an aggregate level, paradoxically, instead of reduction in the percentage of our population below the poverty line, poverty actually increased!

Perhaps, over the years we did improve our ability to estimate people below poverty line (BPL). Possibly, statistical tools improved over the years as did survey techniques and our ability collect data. Or could it be that suddenly we became some sort of realist.

Consider this: At the beginning of the 21st century, we believed that 26 per cent of our population was living below the poverty line. This was vehemently contested by certain economists.

Subsequently, the Planning Commission of India accepted the Tendulkar Committee report which estimated that 37 per cent of people in India live below the poverty line.

. . .

The fundamental flaw in our fight against poverty

Photographs: Reuters

Later, the Arjun Sengupta Report (from National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganised Sector) estimated that 77 per cent of Indians live on less than Rs 20 a day. Yet another estimate, by N C Saxena, estimated that 50 per cent of Indians live below the poverty line.

Wikipedia quotes another study by the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative, using a Multi-dimensional Poverty Index (MPI), found that there were 645 million poor living under the MPI in India, 421 million of who are concentrated in eight north Indian and east Indian states of Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal.

This number is higher than the poor living in the 26 poorest African nations!

One reason for such divergence in the poverty estimates is that there has been no uniform measure of poverty in India. Yet, the fact remains that the percentage of population estimated to be living below the poverty line continues to be high in India.

. . .

The fundamental flaw in our fight against poverty

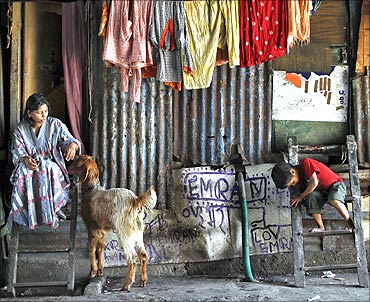

Photographs: Reuters

In fact, it is very high.

But just as one thought we had lost out in our war against poverty the Planning Commission eliminated poverty in India, in one stroke last month, by simply eliminating the poverty line!

That seems to be the surest and simplest way of eliminating poverty in India.

In a document filed before the Supreme Court, the Planning Commission is reported to have stated that an expenditure of Rs 20 per day on essentials for those living in urban areas and Rs 15 for those living in rural India was enough to keep them out of poverty.

. . .

The fundamental flaw in our fight against poverty

Photographs: Reuters

Surely, this must be the most ingenious way to fight poverty. After all, the Planning Commission has lowered the poverty line to such absurd levels that the very idea of poverty has become redundant.

This is not without reason as it may seem on first blush. This requires some elaboration.

The flawed approach to fight poverty

Rs 20, readers may note, again is a round figure. Actually it is Rs 578 per month per head in urban areas. This, as per their report, includes Rs 31 a month on rent and conveyance, Rs 18 a month on education, Rs 25 a month on medicines and Rs 36.5 a month on vegetables!

The unsaid portion of this statement is that anyone spending a paisa more than this is officially not poor as per the Planning Commission's calculation.

. . .

The fundamental flaw in our fight against poverty

Photographs: Reuters

Various experts have opined that the Planning Commission has reduced the calorie intake from 2,100 per day in urban areas (2,400 in rural areas) to about 1,800 per adult Indian.

In contrast, the National Institute of Nutrition (NIN) is reported to have prescribed a minimum of 2,400 calories per day per person. By the way, the average calorie intake available to an inmate at the dreaded Guantanamo Bay is well in excess of 4,000 calories.

Back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that it costs Rs 50 in today's prices even to afford 2,400 calories a day, the minimum suggested by the NIN.

Contrast this with the Rs 20 fixed by the Planning Commission for food, travel, health, education and housing. Absurd isn't it? But what drives such bizarre posturing by the Planning Commission?

. . .

The fundamental flaw in our fight against poverty

Photographs: Reuters

At the core of such computations by the Planning Commission is, perhaps, the late realisation by the government (and the Planning Commission) of the inherent flaws contained in the much-touted Food Security Act.

It may be recalled that the NAC had recommended that the new law should provide a legal entitlement to subsidised food grains for at least 75 per cent of the population, which translates into 90 per cent of the country's rural population and 50 per cent of the urban population.

This 75 per cent of the population is, in turn, is to be divided into 'priority households', which should have a monthly entitlement of 35 kg at a subsidised price of Re 1 a kg for millets, Rs 2 a kg for wheat and Rs 3 a kg for rice; and 'general households' that should have a monthly entitlement of 20 kg 'at a price not exceeding 50 per cent of the current Minimum Support Price' for the three grains.

What this means is that those entitled to 35 kg of grain in the price range of Re 1 to Rs 3 will form approximately 40 per cent of the total population, while those entitled to 20 kg will form approximately 35 per cent of the population. This according to the Planning Commission is estimated to cost in Rs 100,000 crore (Rs 1,000 billion) more in food subsidy to the central government.

. . .

The fundamental flaw in our fight against poverty

Photographs: Reuters

It may be noted that the prevailing food subsidy bill is already estimated to be Rs 80,000 crore (Rs 800 billion). Reference: The Food Security Dilemma by S D Nail -- The Hindu Business Line -- October 16, 2010.

This means that the government will have to recalibrate its fiscal deficit targets and give a go-by to its avowed policy of fiscal prudence. But who cares about fiscal prudence? Not any politician, and definitely not anyone from this government.

But there is yet another dimension to this entire debate. Rough calculations suggest that in order to put into effect this idea of the NAC, the government has to procure anywhere between 80 MT and 100 MT of food grain.

In contrast, the total food grain production in the country is only 240 MT. Naturally, experts like Naik fear that this will result in very low availability of food grains in the open market, leading to a sharp rise in open market prices and, in the process, dynamite the existing order.

. . .

The fundamental flaw in our fight against poverty

Photographs: Reuters

The point that is often forgotten here is that one can borrow money (why, even print currency notes). But we need to actually produce food grains before distribution. The NAC seems to have bypassed this fundamental issue -- one cannot distribute what one does not have, especially when it comes to food grains.

Where is the question of debating the methodology of distribution when there is hardly anything to distribute?

Simply put, the Food Security Act is implementable only when we produce food grains in excess of 350 MT.

However, should we produce food grains in such huge quantities, and given the resultant abundance, there would be no need for the Food Security Bill in the first place.

Realising the gargantuan cost to the exchequer and the lack of grain to bring this idea to fruition, the Planning Commission is attempting a way out.

. . .

The fundamental flaw in our fight against poverty

Photographs: Reuters

That explains why the Planning Commission is rushing to redraw the poverty line to such absurdly low levels. Surely, a mid-way will be found shortly where the Rs-20 benchmark will be doubled to Rs 40 or perhaps Rs 50.

And that will probably ensure that a 'reasonable' number will be benefitted through the Food Security Bill.

The alternative idea of increasing grain production to 350 MT per annum to fight poverty will be buried fathoms deep as it challenges the existing order and threatens vested interests.

Alternatively, the NAC will continue with the flawed idea of planning and distributing poverty, shortages and scarcity. Oblivious of all this, committees and taskforces will continue as usual to meet in five-star hotels to eliminate poverty.

The author is a Chennai-based chartered accountant. Comments can be sent to mrv@mrv.net.in

article