| « Back to article | Print this article |

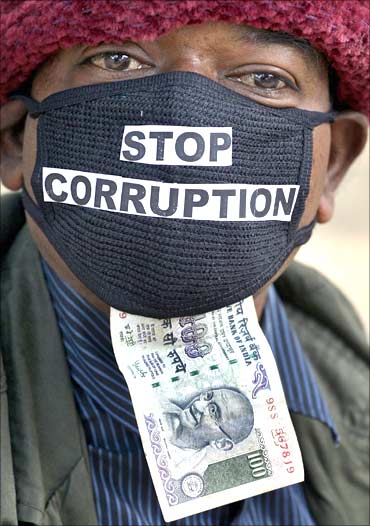

Corruption? The biggest culprit is the Indian state

Corruption is again dominating the news in India.

Long-standing issues like broad attempts to avoid taxes have simmered back to the surface and been joined by new accusations against the wealthy, major companies, and the government.

Scandals have crossed finance, property, and telecom. Crimes have been committed and the guilty should face justice. The biggest culprit, however, faces no punishment and, indeed, is looking to further recent gains. That culprit is the Indian state.

Earlier this year, criticism began to be leveled in India at the underground or 'black' economy. This includes illegal activities but also legal activities that are not declared. All economies have black markets and developing economies tend to have bigger ones.

But the size of the formal Indian economy is now such that estimates of the underground economy at 40 to 50 per cent of the GDP generate very large numbers in the neighborhood of $600 billion.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Corruption? The biggest culprit is the Indian state

This, in turn, spurs outrage at black-marketeers supposedly robbing the Indian people. Except the black marketeers are the Indian people, tens of millions of them.

And the ones being 'robbed' are only the federal and state governments. Moreover, it's often the governments' own fault.

Banned activity doesn't represent lost revenue for the government, since the idea is that it shouldn't occur at all. Where revenue is lost, is in legal activity that is hidden.

But avoiding taxes isn't the only or even the main reason for individuals to hide activities from the government. Rather, it's the difficulty of setting up a business.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Corruption? The biggest culprit is the Indian state

India ranks an awful 165th out of 183 countries in the World Bank's measure of the difficulty of starting a business, and this is actually an improvement over previous years.

Rather than face endless delays and high costs, many ordinary Indians decide to proceed without the necessary authorization and then must hide their businesses. This black market activity is due to a predatory state, which seeks to control Indian entrepreneurship.

Grabbing headlines this month was a similar story about how India has 'lost' over $450 billion due to illegal capital flows (since 1948). Some of this is again money raised in crimes, which was illegally earned and ideally would never have existed in the first place.

The other funds are deemed lost only because the Indian federal government tries to restrict capital movement.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Corruption? The biggest culprit is the Indian state

Despite progress in the reform era, India retains among the tightest controls on capital movement among emerging markets. What would count in most countries merely as citizens and companies investing overseas -- and bringing much of the benefits back home in terms of financial returns, resources, corporate assets and so on -- is not permitted in India.

As happened in all economies throughout history, people followed their self-interest and invested abroad, anyway, only no benefits flowed back to India because the investment has been deemed illegal by the interventionist Indian state.

At the general level, due to the state's jealous protection of its prerogatives, Indian entrepreneurs cannot start a business freely and cannot invest freely.

It is hardly a surprise that corruption is rampant. Indeed, the Heritage Index of Economic Freedom scores India highly in a number of important categories but very low in the connected areas of business freedom, investment freedom, and freedom from corruption.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Corruption? The biggest culprit is the Indian state

In several particular incidents of corruption, the government's guilt is directly apparent. The Commonwealth Games were plagued by overspending, due to lack of transparency and competition in state contract awards.

State-run financials have made loans in exchange for bribes, a problem which would be eased if the state did not dominate the banking system.

The big one is telecom. Improprieties in the government's auction of second-generation (2G) telecom spectrum may have cost as much as $40 billion in fiscal revenue.

Those government and corporate officials who did not follow the law must be punished. But lost in the outrage is the point of a telecom industry. It is not supposed to be a money-making tool for the government.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Corruption? The biggest culprit is the Indian state

It is supposed to improve people's lives, both directly and indirectly through strengthening the economy. And the Indian telecom industry has done just that. It has outperformed expectations in its transformation of Indian society, from medicine to farming. It is a major part of the Indian success story.

There is no telecom failure or betrayal here, quite the opposite. There is only a failure and betrayal of federal coffers.

And even there the unwarranted cheapness of 2G spectrum contributed to a far more dynamic industry and thus led directly to the government's windfall at this year's 3G spectrum auction.

In most cases, the state is causing the problem. In others, the problem is harm to the state, not the people. India is now wrestling with how to deal a decisive blow against corruption.

The answer is plain: Deal a decisive blow against state interference in the economy.

Derek Scissors is research fellow, Asia economic policy, Asian Studies Center, The Heritage Foundation.