| « Back to article | Print this article |

2G spectrum loss? It's actually a boon for mobile users!

The allocation of 2G spectrum in January 2008 has generated a great deal of heat. But it is less clear how much light the passionate recriminations have cast. There are two sets of issues involved in this matter.

First, the policy framework for the allocation of spectrum and second, whether there was any impropriety or illegality by ministers and officials concerned in the way in which the policy was implemented.

The issue of a possible improper implementation of the policy is now the subject matter of several cases before judicial instances.

Click NEXT to read more...

2G spectrum loss? It's actually a boon for mobile users!

These are sub judice, so let us leave it to the courts and look at the policy issue. It is in this context that recriminations about "a presumptive loss to the exchequer" have mainly arisen.

It is worth recalling that the policy for 2G spectrum allocation was established at the end of the 1990s under the Vajpayee government on a first-come, first-served basis.

That government had the foresight to realise that the strategic objective of spectrum allocation should not be maximising revenue but rather ensuring the expansion of telecom at affordable prices.

Click NEXT to read more...

2G spectrum loss? It's actually a boon for mobile users!

The subsequent UPA government maintained this policy for 2G spectrum allocation and it was only changed when 3G spectrum was allocated.

The last allocation of 2G spectrum was undertaken in January 2008. The Comptroller Auditor General's (CAG's) report on this 2G allocation suggested that there was "a presumptive loss to the exchequer" of up to Rs 176,000 crore (Rs 1,760 billion).

Subsequently, the CBI in its assessment brought this figure sharply down to a little over Rs 30,000 crore (Rs 300 billion).

Click NEXT to read more...

2G spectrum loss? It's actually a boon for mobile users!

It has been reported that the CBI asked the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (Trai), the main regulatory body for telecom in the country, to provide an expert evaluation of the presumptive loss to the exchequer.

After several months of examination, Trai concluded that there was in fact no loss to the exchequer but in fact there was even a possible gain of between Rs 3,000 crore (Rs 30 billion) and Rs 7,000 crore (Rs 70 billion).

Trai has also said that prior to 2008, it had not recommended any change of policy to replace the existing policy by the use of auctions for 2G spectrum allocation.

Click NEXT to read more...

2G spectrum loss? It's actually a boon for mobile users!

Understandably, the Trai report was not welcomed by everyone. Yet Trai has, at least one would hope, greater relevant expertise on spectrum allocation and pricing issues than would an auditing or investigating agency.

So unless the methodology or the factual basis that Trai has used is shown to be faulty, should not the presumption be that the Trai report is as, if not more, reliable on the presumptive loss to the exchequer?

Whatever one's view regarding the exact quantum of the presumptive loss to the exchequer as a result of the January-2008 2G allocations, it is worth considering what this "presumptive loss to the exchequer" actually means.

Click NEXT to read more...

2G spectrum loss? It's actually a boon for mobile users!

If the government spends Rs 100 on a welfare scheme and Rs 50 are misallocated due to corruption or incompetence, there is a genuine loss of Rs 50 to the taxpayer. But the presumptive loss to the exchequer from the 2G allocation is different.

No tax rupees were actually lost, but it is argued that the government could have received substantially greater amounts of money had they used some other allocation policy such as auctions.

But suppose the telecom companies who obtained the licenses had been obliged to pay substantially more.

Click NEXT to read more...

2G spectrum loss? It's actually a boon for mobile users!

They in turn would have charged substantially higher prices for mobile telecom and probably provided poorer coverage and service (since they may not have had sufficient financing left after paying the high prices to roll out the physical infrastructure at the same level that they actually did).

This would have meant that India's citizens, you and I, would have had to pay substantially higher tariffs and received poorer quality service, limiting the use of mobile telephones.

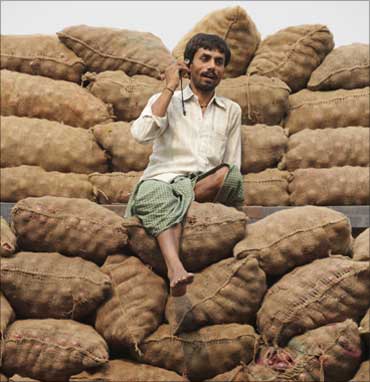

It would have meant that the remarkable expansion of mobile telephones seen in recent years would not have taken place. Today the common man or woman on the street can – and does – use mobiles.

Click NEXT to read more...

2G spectrum loss? It's actually a boon for mobile users!

Moreover, the government would not have received the permanently higher stream of tax revenues from the expansion of the mobile telephone networks.

Nor would the economy have benefited - in terms of both productivity and growth - from the great improvement in communications brought about by the mobile telephone revolution.

In effect, substantially higher spectrum prices would have acted as a tax on mobile users.

Click NEXT to read more...

2G spectrum loss? It's actually a boon for mobile users!

And since there are more poor users than rich ones, it would have been a regressive, anti-poor tax at that (unless of course poor users were excluded altogether by the high mobile tariffs!).

Thus, the presumptive loss to the exchequer from 2G allocations actually represents a huge benefit to citizens - to you and I!

Those whose job it is to maximise government revenues might understandably lament this "failure".

Click NEXT to read more...

2G spectrum loss? It's actually a boon for mobile users!

It is more difficult to understand why other critics, especially BJP critics whose party's government after all established this policy, should join in the shrill lamentations over the government's failure to extract as much money as possible from our citizens.

India's citizens on the other hand, especially low-income users, can be grateful for the policy.

It has allowed us to enjoy the benefits of what is probably the largest and cheapest mobile telephone system in the world. At least, this is one thing we have that is world-class.