The Tata Consultancy Services-Smart Manager Case Contest is the oldest and most prestigious competition of its kind in India.

Apart from a one-year free subscription to The Smart Manager, India's first world-class management magazine, winners from the 'manager' and 'student' categories stand to win cash prises of Rs 25,000 each.

All you have to do is read the case, see the question you have to answer on the last slide, . . .

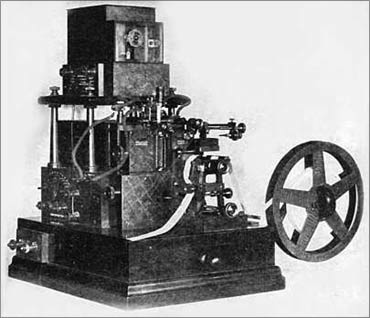

The famous Morse code was developed as a quick and easy way of sending messages. With the Morse code, operators could send and receive messages at speeds of up to 35-40 words per minute.

This seems incredibly slow when compared to the speed of communications today, but prior to the telegraph, the only way of sending messages was by boat or by messenger on horseback. It could take six months for a letter to go from India to Britain.

Once a continuous telegraph link was established, however, messages could travel around the globe in a matter of minutes.

So revolutionary was this technology that very few appreciated it at first. The first telegraphs were patented in 1837, with the inventors hoping to attract support from the government.

. . .

But it took another six years for the British and American governments to get around to building telegraph lines and holding trials.

As one of the inventors said during these trials, "If it will go ten miles without stopping, I can make it go around the globe".

But even then the governments were not convinced, and the inventors were forced to turn to the private sector to raise capital.

Progress was slow at first. By 1846, there were still less than 100 kilometers of working telegraph lines around the world. Slowly, however, interest began to build, and then, as the true importance of the telegraph began to dawn on people, it exploded.

. . .

New telegraph companies sprang up everywhere. By 1852, there were nearly 50,000 kilometers of telegraph cable around the world, and the next forty years saw near continuous expansion.

In 1858, the first trans-Atlantic cable was laid, connecting Europe and North America.

The invention and expansion of the telegraph came at a time when the European and American economies were experiencing rapid growth and when international trade was beginning to boom.

In order to conduct business internationally, companies needed information on what was happening in other companies and markets. Large companies, especially banks, had their own information-gathering systems, consisting of paid agents living and working in major financial centres.

. . .

These agents collected information on prices, competitors and their activities, political trends and so on, and forwarded this information to their employers. Such information systems were, however, expensive and only companies with deep pockets could afford them.

Smaller investors unable to afford such systems could buy information from news agencies and entrepreneurs who digested information from local newspapers and news sheets and sold it on a subscription basis to clients in other cities.

But all such information had to be transmitted by post and took days, sometimes weeks, to arrive. By the time managers had the information they needed to make investment decisions -- whether to invest in a new railway in another country, for example, or to buy government bonds -- that information was often outdated.

There was a business opportunity here, and one man saw it. Paul Lorenz was a German writer and journalist who had been forced into exile in France in 1848 because of his political activities.

Needing employment, he worked briefly for a small French news agency, Michel et Cie, which packaged and sold information in the manner described above. Michel experimented with sending news by telegraph, but without much success, partly because there were still many gaps in the telegraph network and partly because the telegraph companies themselves were not very cooperative.

. . .

Some of the early telegraph companies also had ambitions to move into information-gathering and tried to control the content of what was sent over their networks, freezing out competitors.

The problem was that they were good at managing networks but had no experience of information-gathering (imagine what would happen today if a mobile telephone company decided it wanted to become a news agency). So their efforts failed as well.

After leaving Michel's employ, Lorenz moved on to a succession of jobs, including establishing a newspaper of his own, which quickly failed.

But he continued to hark back to his experience at Michel, pondering on the potential of the telegraph. In 1849, he set up a small news agency of his own with the specific purpose of transmitting financial information by telegraph to interested clients in other cities.

Learning a lesson from Michel's experience, he offered to cooperate with the telegraph companies, and, for a time, worked in partnership with several of them. But, seeing the business beginning to become successful, Lorenz's partners decided to take control.

. . .

They told Lorenz they no longer needed him and that they would handle the information-gathering end of the business themselves.

Lorenz was not deterred. He knew the telegraph companies lacked experience in this field and would therefore fail. He relocated to London, then the world's leading financial centre, where there was a strong demand for financial information.

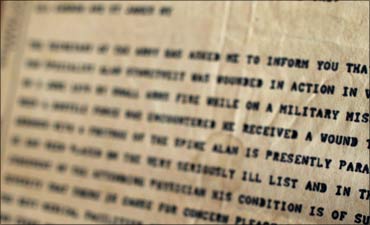

Next, he began to develop his own network of correspondents and agents in other major financial cities. These people would gather information and pass it back to London in coded messages by telegraph.

For example, the latest prices from the Paris Bourse and other European stock exchanges were sent by telegraph to London and sold to client subscribers. At the same time, information from London was transmitted back to the Continent and sold to clients there.

. . .

The information, if not quite real time, was at least available within 24 hours and was also comparatively cheap. This meant there was now a more level playing field in terms of the availability of financial information.

A greater number of people had access to an increasing amount of information at the same time, and decisions could be made on a more equitable basis. This was a major factor in the increase in cross-border trade through the latter half of the nineteenth century.

But while gathering and selling financial information was a lucrative business, Lorenz had spotted a further opportunity in gathering and selling news to newspapers.

At this time, there were hundreds of newspapers in Britain alone -- and thousands across Europe -- all hungry for stories to tell their readers. Big, prestigious newspapers like The Times already had their own networks of correspondents around Europe and had begun using the telegraph to file stories.

. . .

Lorenz knew he could sell news to smaller papers but his priority was to engage with the big ones as well: with big papers for clients, his own brand and reputation would be reinforced.

Through the 1850s, Lorenz demonstrated what his agency could do. He built a reputation for gathering reliable and accurate news and transmitting it across Europe faster than the big newspapers could.

On one occasion, his correspondent in Paris was able to transmit a copy of a speech by the French emperor in advance to London, where it was printed in the newspapers, so that readers could quite literally read the speech as it was being made.

During the war between France and Austria, Lorenz's correspondents sent dispatches directly from the battlefields of Magenta and Solferino, so that newspaper readers elsewhere in Europe read about these events the morning after they had occurred.

. . .

This was unheard of -- back in 1815, news of the Battle of Waterloo had taken a week to reach London, less than two hundred miles away. Now, people were reading about events almost as they happened.

The impact was similar to that of CNN's coverage of the Gulf War, when people watched the bombardment of Baghdad almost as it happened. Despite all this, the big newspapers in England, France and Germany refused to use Lorenz's services.

They preferred to use their own dedicated networks of correspondents, even though these were often slower than Lorenz's. They had their own methods of working and did not want to see these disturbed.

More conservative editors also saw Lorenz's agency as 'new-fangled', something they did not care to get involved with. By 1859, he had signed deals with just two major newspapers.

. . .

Your question

How could Lorenz break down the resistance of the major papers and crack this market?

Click on the logo below to submit your analysis. Or you may want to mail your analysis to casestudy@thesmartmanager.com.

(Note: Please check your email after registration for your username and password).

All right reserved with The Smart Manager