| « Back to article | Print this article |

Tata's brand building: A roundabout tale

Contrary to perception that the Tatas have been an industrial giant, the 100-year-old-group has had a history of producing fast moving consumer goods and cosmetics.

The group had two firms -- Tata Oil Manufacturing Company and Lakme Ltd -- which produced some enduring brands in the beauty, laundry and personal care space.

Lakme, for instance, remains the most visible example of this legacy, emerging as a strong home-grown brand in a world dominated by international names.

Tomco produced popular soaps such as Hamam and Moti as well as Nihar Hair Oil, which prompted Hindustan Unilever -- then Hindustan Lever -- to make a successful bid and eventually take over the company in 1993 when Ratan Tata chose to hive off the business.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Tata's brand building: A roundabout tale

HUL also inked a 50:50 joint venture with Lakme in 1998 and subsequently bought the Tatas' stake in the company to take full control of it.

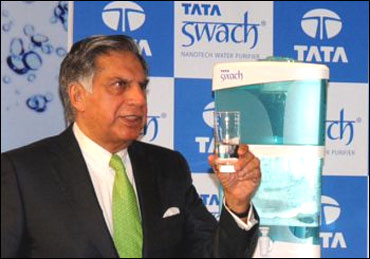

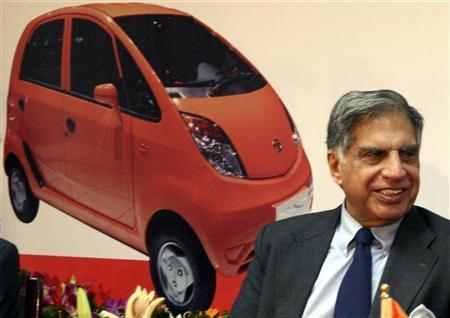

Despite all this, the Tatas appear to have struggled with brand building in the past few years with products such as Nano, Ginger Hotels and even Swach failing to live up to the hype.

Consider this: from an envisaged 20,000 units a month, Nano today sells less than 6,000 units a month. This is despite being priced 60 per cent lower than its closest rival -- Alto -- which comes at an ex-showroom price of Rs 255,000 in Mumbai.

The story is no different with Ginger.

The original plan was to set up 30 properties across the country by 2010, but there are only 26 Ginger budget hotels up and running at the moment.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Tata's brand building: A roundabout tale

In a market where there is no dearth of options in the economy segment with decent two-star and three-star hotels dotting the landscape, Ginger does not stand out, say experts.

Thanks to inflationary pressures, Ginger has also been unable to hold on to its under Rs 1,000 price line either, which was to be its unique selling proposition, besides of course the promise that it offered a smart and chic do-it-yourself service that was uber cool for the travelling executive.

According to experts, the problem with Ginger has been one of positioning.

On Swach, its maker Tata Chemicals says that it sold one million units cumulatively in the last financial year.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Tata's brand building: A roundabout tale

For a brand that was launched only two years ago, Sabaleel Nandy, head of the water purifier business at Tata Chemicals, says that the sales figure is not bad at all.

"We are not present in all states of the country.

"But we are ramping up distribution," he says.

Market experts insist that rival brands such as Aquaguard and AquaSure from Eureka Forbes, Hindustan Unilever's Pureit and the Hema Malini-endorsed Kent induce far greater recall than Swach does among water purifiers in India.

According to Nandy, drawing a comparison between Swach and its rivals would be unfair since it is a fairly new entrant in the space. "Give us some time," he insists.

But even then, Tata Chemicals seem unable to shake off the tag of not being the most preferred brand in its category.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Tata's brand building: A roundabout tale

This is despite an affordable price tag of Rs 899 and the promise that you do not need electricity to run the water purifier.

It also does not use either chlorine or bromine to purify water, but instead, depends on processed rice husk ash infused with nano silver particles to kill disease-causing bacteria, germs and other organisms.

Nandy says that Swach marries traditional science and modern chemistry. Then where lies the problem?

According to market experts, the company has not done enough when it comes to advertising what the product is all about.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Tata's brand building: A roundabout tale

Which is why consumers at large remain clueless about Swach.

While Tata Chemicals has only now begun pushing Swach on national television, educating consumers about its silver nano technology, experts say that the company may have to do a lot more to increase visibility of the brand.

"The water purifier market is fairly crowded with local as well as national players," says Harish Bijoor, CEO, Harish Bijoor Consults.

"Every one is fighting for the mindspace of the consumer using science as a tool, so you have to go the extra mile if you have to stand out of the clutter," he says.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Tata's brand building: A roundabout tale

For instance, Eureka Forbes uses not just traditional advertising, but also its army of salesmen to push its products aggressively door to door.

Which is why recall for products of Eureka Forbes including its water purifiers remains high among lay consumers.

HUL, on the other hand, has a strong distribution model to push its products apart from traditional advertising, which has been its strength over the years.

Experts say that part of the reason for some Tata products failing in the marketplace has not only to do with inadequate advertising as has been the case with Swach, but also on account of technical issues.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Tata's brand building: A roundabout tale

Nano is a fine example.

It struggled with product glitches following its launch in 2009.

Although executives from Tata Motors insist those drawbacks have been corrected with the new edition that was launched this year, the image of a car that can go up in flames easily simply refuses to go.

"First impressions are quite often last impressions," says Anmol Dhar, managing director, Superbrands India.

"The Tatas are great truck makers, but not necessarily producers of great cars.

A good example of this is Indica and Indigo, which failed to cut ice with consumers.

They are used as taxis today.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Tata's brand building: A roundabout tale

The Nano's initial hiccups only served to reinforce this notion of poor production quality, which is why even with a new edition this year, the Nano has failed to take-off."

According to experts, the Rs 100,000- price tag (now Rs 155,000) ironically does not make the Nano desirable in an aspirational category such as cars.

"When you set out to buy a car, it is not just about going out and getting any four-wheeler, it is a culmination of a dream," says the marketing head of an international car company.

"Even at the entry level, consumers seek a product that can add to their status and prestige.

"I think the Nano somehow is unable to meet this requirement, which is why even after targeting the new edition at youth, it hasn't clicked."

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Tata's brand building: A roundabout tale

Industry insiders say the Nano is a flop internationally, too.

It is exported only to Sri Lanka and Nepal with plans to launch in markets such as the US, Europe, Latin America and the Far East yet to see the light of day.

Tata Chemicals, in contrast, has expanded into three areas: living essentials, industry essentials and farm essentials -- from a producer of largely inorganic chemicals such as soda ash, a base ingredient in many industries.

Under living essentials comes the company's consumer businesses - salt, water, branded commodities and neutraceuticals.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Tata's brand building: A roundabout tale

Under industry essentials comes the core bulk and specialty chemicals and cement, while farm essentials dwell on crop nutrition and protection and seeds.

Company executives say that the transformation from a commodity company to one providing complex solutions in different areas was led by the need to be relevant in changing times.

In the last few years, Tata Chemicals has made a series of acquisitions in inorganic chemicals and has also invested heavily in agri-business.

It is now focusing its attention on its research and development capabilities.