| « Back to article | Print this article |

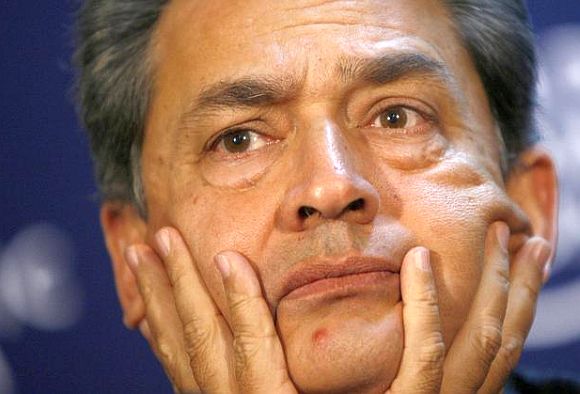

'Rajat Gupta's conviction does not mean the end of the Indian story in America'

‘When the news of Gupta tipping Rajaratnam broke, the Establishment, which he had so carefully cultivated during his 40 years in America, quickly moved to distance itself from him. This is one of the hardest things for Gupta to bear now,’ Anita Raghavan, author of The Billionaire’s Apprentice, tells Rediff.com’s Arthur J Pais in a fascinating interview.

The young man had told his superiors at the Ripon College in Calcutta, while asking for casual leave, that he had diarrhea. Soon he was at a barber’s shop where he had his hair dyed, clipped and curled.

And soon he was Student 160 writing an economics exam. When vigilant supervisors checked his ID, the ‘student’ fled the exam hall, fell, and his make-up, which included a mustache and dark glasses, dropped out.

Ashwini Kumar Gupta was sentenced to six months of hard labor, a sentence upheld on appeal.

That sensational trial some 78 years ago, author Anita Raghavan tells us, was a betrayal of the system for a noble cause. Gupta was impersonating a rich student who had been tutored by him, and the money he received in return, only a few close comrades knew at the time, was given to the Socialist Party.

Different kinds of recent betrayals in the financial world in America feature in Raghavan’s thoroughly researched (based on some 200 interviews, extensive library research and court reporting ) and engaging book, The Billionaire’s Apprentice/The Rise of the Indian-American Elite and The Fall of the Galleon Hedge Fund.

Ashwini Gupta’s son Rajat Kumar Gupta is the apprentice in the title, and the Sri Lanka-born Raj Rajaratnam, who depended on Indians in high positions at billion dollar firms to provide him inside information, is the billionaire in the title.

Raghavan projects the ascendancy of the Indian community in America in the context of the struggle the parents of many players in her book underwent in British times.

The Galleon case told many ‘stories in a single story,’ Raghavan, a prize-winning reporter for The Wall Street Journal and Forbes, notes.

'It was a tale of early migration of Indians to the United States, their breathtakingly swift rise and heady success in America, and last but most important, the emergence of a second generation of Indians who would ignore the blind loyalties their fathers held to kin and country and serve as a model of assimilated Indians in America.’

When The Galleon Group, one of the world’s largest hedge funds, collapsed following its involvement in an inside trading scandal four years ago, the conviction of Rajaratnam, and his accomplice Gupta, the trend-setting former head of the management consultancy McKinsey, transformed them from heroes to vilified men.

Gupta was for many years the eminence grise of Indian-American business.

When the government moved against Gupta, many refused to believe he had provided crucial tips to Rajaratnam that added many millions to Galleon’s fortune.

After all, Gupta was a man who had made McKinsey a global consulting juggernaut and who served on the boards of Goldman Sachs, American Airlines, and Proctor & Gamble and counted President Bill Clinton as one of his friends. He did not need the dirty money, many felt.

Only after the government charged Gupta in 2011 with conspiracy to commit securities fraud, Raghavan says, did it come to light how his life and ambition changed alarmingly after he left McKinsey in 2000 and begun admiring people like Rajaratnam and their wealth.

How did you come across the family secret about Rajat Gupta’s father Ashwini Kumar Gupta?

It was common knowledge in Calcutta. I had visited the city for my research even before Gupta’s trial began in New York. But journalists never wrote about it - I guess in deference to Rajat’s father who was one of them.

I should have guessed there was a secret there; why else would an academic give up that world for journalism? (chuckles).

As I delved deeper into the story, I realised Ashwini’s transgression was a source of great shame for the family, which was steeped in academia. And it cost him a number of career opportunities.

But as a freedom fighter he was close to the family that owned Ananda Bazaar Patrika and they helped him re-establish himself.

Eventually he rose to become a prominent journalist in Calcutta and was known to (Jawaharlal) Nehru on a first-name basis.

To corroborate the story, I was fortunate in having access to the vast newspaper archives of the British Library in London.

To my astonishment, I found a series of articles chronicling this tragic story and came to realise it was a cause celebre in Calcutta at the time.

Your book says at the time of his father’s cremation, the son said, beseeching a higher power: ‘Who will show me the way in the world’?

Yes, I think despite Gupta’s stoicism later in life, the young Rajat was deeply affected by his father’s sudden death.

What’s interesting is that he did not speak openly about his father. His first office-mate at McKinsey said Rajat never told him that both his parents had died.

I always thought it odd that Rajat never made more of his father’s freedom fighting activities when he came to the United States, particularly as Americans love such stories.

After all, the senior Gupta and Americans had fought the same enemy, the British.

You also write, ‘Ashwini Gupta seems to have committed an ignoble act for what his only close associates knew to be a noble cause, love of the country, while three quarters of a century later his son would throw away reputation for an ignoble cause.’

Rajat’s father was not only a freedom fighter, but he was a socialist and a strong believer in a socialist India.

As I said, he was a friend of Jawaharlal Nehru’s. Rajat greatly admired his father and both men shared a deep love for India, but Rajat would go on to carve a very different destiny for himself.

His father had no hesitation in burning bridges for a noble cause, but Rajat constructed his career around building bridges. In fact, he was an Establishment man from his very early years.

When there was a rebellion by the students at IIT against the head of the institute, he sided with the school.

One of Rajat’s salient qualities that emerged from my interviews with people who knew him at McKinsey is that he was a soft spoken person who strove for compromise.

I think it was this quality that helped him rise to the top job at McKinsey which at the time was a very white-shoe firm.

There were a number of other candidates for the managing director post in 1994, but Rajat stood out, particularly over a successful German candidate who wasn’t popular with the Americas because he was too outspoken and assertive.

To me, the great irony of this story, of course, is that when the news of Rajat tipping Raj Rajaratnam broke, the Establishment, which he had so carefully cultivated during his 40 years in America, quickly moved to distance itself from him.

I think this is one of the hardest things for Gupta to bear now.

'Rajat Gupta's conviction does not mean the end of the Indian story in America'

Was this the original title of the book?

I toyed with a couple other titles before settling on The Billionaire’s Apprentice.

The original title was Sons of the Morning which came from one of my favorite English hymns and also reflected something important about the South Asians in this story.

They were India’s best and brightest, the great hope of a dawning nation.

Another title I looked at was Two Kings.

Raj Rajaratnam used to call himself King of Kings and tell people that his two names - Raj Raja - meant exactly that.

If Rajaratnam was a king because of his enormous wealth and outsised ego, Gupta was a king because of his nobility of spirit.

Here was a man who came from a comparatively humble background.

Unlike Rajaratnam, whose father was an executive at the sewing machine company Singer in Sri Lanka, Gupta’s family, though rich in learning, was poor in material wealth.

Gupta had to cross oceans and struggle in the beginning; when he first joined McKinsey, he had only two shirts. But he slowly worked himself to the top, breaking glass ceilings.

It seemed that for most of his life, he was a good king, drawing on his influence to raise money for charities he cared about and build a world-class business school in India

And yet he became the apprentice to Rajaratnam.

Yes, it is stunning to think that happened.

These two men had very different personalities. Rajaratnam was a street fighter with all the savvy and smarts that come with being one. He did not care what rules he broke; in fact, he enjoyed pushing the envelope.

He would boast to employees that when he combined two apartments in tony Sutton Place where his wife and kids live on one floor and his parents on another, he told city officials that he was Jewish and needed two kitchens to follow Jewish dietary laws where preparation of meat and dairy are separated.

People thought it was an idle boast, but when I called the New York City buildings department I learned that he indeed had asked for a religious exemption in seeking to have two kitchens in the apartment.

Rajaratnam also had no problem using people for his own ends and not keeping up his promises.

When one of the young men working for him said he wanted to start his own fund, Rajaratnam gave him warm encouragement, offering him office space and telling him that he would put money into his venture.

But a week before the man was set to start his own fund, Rajaratnam pulled the rug out from under him: He told him to look for office space.

'Rajat Gupta's conviction does not mean the end of the Indian story in America'

Rajat Gupta started giving inside tips to Rajaratnam only after his three terms at McKinsey were over. What led him to become an apprentice to Rajaratnam?

Right. When Gupta started at McKinsey and for much of the early part of his tenure, the pay scale between investment banks and consulting firms was comparable.

In fact, when Gupta started at McKinsey in the early 1970s, Wall Street was in a bear market and laying off employees.

Consulting was actually a more promising profession that paid just as well as investment banking.

But by the 1990s, the pay differential between Wall Street and consulting had diverged considerably.

Analysts who stood at the bottom of Wall Street’s food chain were pulling in tens of millions of dollars. Consultants were earning nowhere near that.

By the time he retired, Gupta was taking in about $5 million and that was far more than his predecessors at McKinsey but nothing like his peers on Wall Street - the Jamie Dimons and Hank Paulsons.

I think Gupta came face to face with this reality when he moved to the East Coast in the late 1990s. He was starting to mingle with a new crowd of prominent financiers like Henry Kravis who were in a position to bankroll their pet philanthropic projects.

Instead of being check collectors - the role Gupta played when he raised money for the Indian School of Business and later the American India Foundation - they were check writers.

It’s interesting when Gupta started AIF, he had a very hard time raising money from the Indian-American community in the United States.

So naturally when Rajaratnam wrote out a big check, Gupta was not only delighted, but he was also impressed. Their relationship was limited to business though.

The two were not personal friends. They did not socialise or go on a holiday together; for instance, Gupta was not at Rajaratnam’s 50th birthday party bash in Kenya in 2007. And their wives never shopped or lunched together.

I think particularly as Gupta started mingling in a new circle in Manhattan, he came to feel that he didn’t stack up.

After all, he was the man who was elected head of McKinsey three times in a row by the partnership, he was the man who was close to Bill Clinton, Kofi Annan, and Bill Gates.

He was one of the few Indians to be invited to all three White House dinners for Dr Manmohan Singh in the past decade by Republican and Democratic Presidents alike.

But at the end of a storied career in consulting, he was still in a position of being a check collector, not a check writer.

I think that rankled.

Oddly, I think Gupta respected and admired Rajaratnam for his wealth.

While Rajaratnam came from a more affluent family than Gupta, he had challenges in life - he didn’t start his career at one of the Establishment investment banks on Wall Street like Goldman or Morgan Stanley - yet he managed to build a hedge fund behemoth out of nothing.

Rajaratnam very cleverly sensed this vulnerability in Gupta and charmed him, showing him deference and praising him by calling him a South Asian rock star.

As Gupta fell under his spell, he lowered his guard.

During the trial Gupta’s lawyer insisted that the relationship between his client and Rajaratnam had soured at the time of the alleged tipping, that Gupta had lost over $10 million invested in a business with Rajaratnam.

Spectators sitting in the gallery of the courtroom found it difficult to believe those claims.

'Rajat Gupta's conviction does not mean the end of the Indian story in America'

If that was true, people wondered, why didn’t Gupta sue Rajaratnam and why after the dispute between the two started in the fall of 2008 did Gupta continue to keep in touch with Rajaratnam even lobbing a solicitous call to him in October when the markets were in freefall?

At one point, Goldman’s lawyers asked Gupta to disclose the name of the lawyer that he had retained to sue Rajaratnam over the investment loss.

But the lawyers never received the name.

After the trial was over Rajaratnam talked about how he was ‘betrayed.’ You quote him telling Newsweek, ‘The Americans stood their ground. Every bloody Indian cooperated.’

That is not entirely true.

One of Rajaratnam’s proteges, Adam Smith. who had been carefully groomed by Rajaratnam during his time at Galleon, cooperated and testified against at his trial.

But Rajaratnam was never one to let the facts get in the way of a good story.

At one point when news that Gupta was being investigated was first revealed, Gupta was heard complaining in a phone call outside a supermarket that nobody was returning his calls.

There were two kinds of reactions. On the East Coast, even among those who might not have returned his calls, there was some sympathy for him.

Remember, a lot of the South Asians who worked on Wall Street were members of Gupta’s generation; some had even gone to IIT like him.

They wanted to believe that the tips Gupta allegedly gave Rajaratnam were more the result of a slip of the tongue.

I am sure some might have even wondered about their own position and the danger they risked of running into a similar problem.

On the West Coast, among the leaders in the Asian community in Silicon Valley there was little sympathy for Gupta.

The feeling was that Rajat Gupta was yesterday’s icon.

For instance, when Gupta supporters were trying to build a Web site of friends that were supportive of him in the run-up to his trial, Vinod Khosla, the prominent venture capitalist and co-founder of Sun Microsystems, made it very clear that he didn’t want to have anything to do with Gupta.

And when Gupta reached out to friends for letters of support before his sentencing, Americans like Bill Gates, who knew Gupta from his philanthropic work in the area of AIDS, wrote to the judge; but very few Silicon Valley Indians did.

Rajaratnam gave away several millions to Tamil charities and to rehabilitate the victims of the 2004 tsunami. Gupta started AIF.

What do you make out of these charitable endeavors and what do you think of corporations getting involved in philanthropy?

Philanthropy has always been a way for wealthy people to preen and show off their wealth and I think Rajaratnam used charity very adeptly as a networking tool.

That said, I think all charity is commendable and even if the motivations for engaging in charitable work are not always pure, one shouldn’t discount the philanthropic projects of prominent financiers.

Today, when so many charities are strapped for cash, I think it’s important for corporations to be involved in philanthropy, but it is also key for charities to operate independently and not to be unduly swayed by the philanthropists that bankroll them.

'Rajat Gupta's conviction does not mean the end of the Indian story in America'

What was the toughest part in researching the book? And what were your emotions at the sentencing of Gupta?

I think the hardest part of the book was writing about Gupta, a man whom so many revered and considered an icon, who was now convicted of an unthinkable crime.

I spoke to many of Gupta’s friends and former colleagues who were incredibly loyal to him and I think that says a lot about him as an individual.

It was very different to the image I developed of Anil Kumar. Even some who knew him from his childhood days acknowledged that as his influence at McKinsey grew during the 1990s, Kumar became arrogant and high-handed falling prey to the age-old adage of pride comes before a fall.

You mention in passing that when Gupta was sentenced, and Rajaratnam was sent to prison, many in the Indian-American community thought the worst was over.

So when the big scandal over Mathew Marthoma came about, many in the community were relieved, thinking he was not an Indian.

He was Indian, having changed his name as a young boy.

I think when it emerged that Marthoma was Indian, there was a collective gasp of horror among the Indian-American community, a feeling of when will this story of South Asians being involved in insider trading cases end?

This is why it is so important that the Indian-American community realises that a misstep by one reflects on all and the recent cases involving Gupta, Kumar and now Marthoma will cast a long shadow on the community for some time to come.

Anil Kumar, a senior partner at McKinsey and a protégé of Rajat Gupta, who admitted taking money from Rajaratnam for offering inside tips, concocted a scheme involving his domestic help, Manju Das.

What happened there? And would you say that Kumar was least affected in this scandal compared to Rajaratnam and Gupta?

Kumar arranged for the illicit payments he was getting from Rajaratnam to be funneled to Manju Das, his housekeeper, who he said was an offshore investor.

Das actually lived with him and his wife in California, so that was a lie.

But Kumar fell compelled to dissemble because he didn’t want to risk McKinsey knowing of the payments he was receiving for moonlighting for Rajaratnam.

In one sense, yes, Kumar was the least affected by this scandal.

Unlike Rajaratnam and now possibly Gupta, he didn’t have to serve any prison time. He was just given two years probation.

But in the court of public opinion Kumar has taken a bit hit.

Among his fellow Doscos - boys who went to (India’s prestigious) Doon school - he is considered a ‘snitch’ which in their book may be worse than trading on inside information.

'Rajat Gupta's conviction does not mean the end of the Indian story in America'

Preetinder Singh Bharara, better known as Preet Bharara, has successfully prosecuted many white collar crimes.

But it was the Rajaratnam case that brought him wide attention, followed by Rajat Gupta’s case.

You have interesting observations in your book about this, and why Bharara went after Gupta in particular.

Bharara had little to do with the building of the Rajaratnam case - it was actually something he inherited when he became US Attorney in August 2009.

I think it was important for him to pursue the Gupta case because he and his office had come under fire for not charging any of the culprits behind the financial crisis in 2008.

While Gupta certainly did not have a hand in constructing shoddy mortgages or fueling the financial meltdown, he was a big fish in the financial world, a man who served on the boards of countless companies and some of America’s biggest such as Goldman Sachs and Procter & Gamble.

By indicting him, Bharara would be able to send a strong message to corporate America that board members who share corporate secrets outside the boardroom will be prosecuted and could potentially face jail time.

Isn’t this book also a cautionary tale?

It is, indeed.

Indians immigrants in America have had a magical journey for over four decades.

People used to talk about the success of Chinese immigrants in recent decades, but in terms of income and education what the Indian community has achieved is far more impressive.

We have a precious legacy to carry on.

What gains we have made in education, politics or business, we owe a lot to the generations that came before us.

And so it is even more important for our community to be exemplary in whatever we do.

Rajat Gupta was a very good example of assimilation and retaining one’s culture. He never gave up his Indian heritage; his home was decorated with Indian artifacts. His four daughters called him Baba.

And yet he was very much part of the American landscape.

One of the most important festivals to the family was Thanksgiving when he would often think of the extended family and pay tribute to a young nephew who died of leukemia.

And yet the American dream soured for Gupta.

Gurcharan Das, former head of Proctor & Gamble and an influential author, felt Gupta’s conviction had ‘stained the India story.’

Das makes an important point. For decades, Indian managers had thrived on the reputation of the likes of men like Gupta. He was a trail blazer.

I was a young reporter at The Wall Street Journal when he became the head of McKinsey and I remember reading the story in awe and feeling a sense of pride well up in me.

Following his success, many Indians acquired a reputation in the West as being highly effective managers.

Books such as The New India Way, by four professors at the Wharton School, extolled the imagination, drive and accomplishments of Indian managers.

Gupta had many admirers - both Western and Eastern - and he could waltz through different worlds, business and philanthropy, India and America, very easily.

But his conviction does not mean the end of the Indian story in America.

I draw in the book on something that David Ben-Gurion, the founder of Israel, reportedly said: ‘In order for Israel to be counted among the nations of the world, it has to have its own burglars and prostitutes.’

Every accomplished major immigration group in America has had its heroes and fallen heroes. The Italians have the Mafia. The Indian community today is vibrant, strong in numbers and rich in diversity.

Let us not forget Preet Bharara, the US Attorney in this case, is of Indian origin and so is the SEC’s top enforcement lawyer, Sanjay Wadhwa.

Indian Americans today are no longer confined to walking the corridors of corporate America; they now stalk the halls of justice.

Gupta’s fall from grace is tragic and heartbreaking, but we also know that much like the immigrant groups before them, Indians too have attained a certain security and once unimaginable positions in American society, in the courts, in universities, in business and in Hollywood.

We are not only large in numbers - some three million - but we are also very diverse.

As I conclude my book, ‘No longer fearful of standing out, the children of twice blessed are all too eager to stand up.’