| « Back to article | Print this article |

Is Gujarat really a success story?

Data on growth in rural jobs and on progress in social indicators don’t bear out the story of uniform and high progress

Business Standard reported last month about the farmers protest against land acquisition for the Special Investment Region (SIR) in Gujarat’s Mehsana district.

This is where automobile major Maruti Suzuki’s proposed factory is coming up. Farmers are saying if the government does not withdraw its decision on the SIR, they might agitate against the upcoming factory as well.

This is not an isolated case. According to reports, farmers from several villages in Bhavnagar district are protesting against land acquisition for the nuclear power plant proposed in the district.

Click NEXT to read more...

Is Gujarat really a success story?

A stir is also on against setting up of a railway hub along the Delhi-Mumbai industrial corridor. Says former state cabinet minister Jay Narayan Vyas: There is some discontent. But we will sort this out very soon.

Gujarat’s land acquisition model was cited as a success story till recently. The ease of acquiring land was one factor behind companies such as Tata Motors, Ford and Maruti setting up plants in the Sanand-Mehsana belt.

This perception has begun to change. Is accelerated agricultural growth behind farmers’ refusal to let go? Or is relative deprivation driving farmers to the path of protest?

Click NEXT to read more...

Is Gujarat really a success story?

Who benefits?

The participation of small and marginal farmers has gone down in Gujarat’s rural growth, says Atul Sood, associate professor of economics at Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University.

He and nine other scholars have come out with a book, Poverty Amidst Prosperity: Essays on the Trajectory of Development in Gujarat, which suggests while the growth numbers seem impressive, the benefits have not percolated down.

Citing National Sample Survey (NSS) data, he says employment in rural Gujarat has declined in the past five years despite high growth in the agricultural sector.

The reason, he says, is the reduced participation of small and marginal farmers in high value crops. Employment growth in urban Gujarat has not been very good either, he adds.

According to him, NSS data shows growth in employment for the period 1993-94 to 2004-05 was 2.69 per cent annually; for 2004-05 to 2009-10, it was down to almost zero.

The focus of growth has been on profit maximisation and not job generation and helping the poor, says Sood. That is why the rate of reduction of rural poverty in Gujarat has been better than the national average but less than states like Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu, he adds.

Click NEXT to read more...

Is Gujarat really a success story?

Does this mean Gujarat’s has been jobless growth? IIM Ahmedabad professor Anil Gupta counters this.

He says most of the job generation has happened in the services sector. If employment opportunities are not available here, why do people from other areas migrate to Gujarat? he asks.

He adds the lead indicators like credit flow to businesses, number of start-ups doing well and also the number of new brands getting registered in the state suggest job creation has been buoyant. Ahmedabad-based industrial advisor Sunil Parekh agrees.

He says the manufacturing sector in the state has never been known for creating many jobs, due to reliance on automation. Sectors like chemicals and petroleum that dominate the industrial scene in Gujarat are not known for creating many jobs.

But the services sector looks very buoyant, Parekh argues. Most of the jobs in the services sector are in the informal sector. And, don’t forget the number of self-employed, Vyas adds.

Click NEXT to read more...

Is Gujarat really a success story?

Below par

On social indicators, though, Gujarat’s performance is decidedly below par, despite the marked improvement in the economic indices.

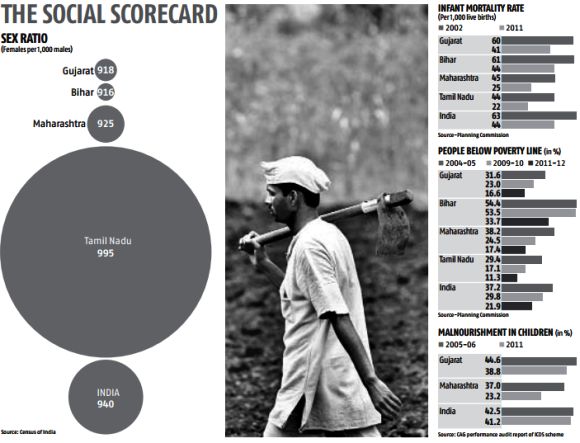

The percentage of malnourished children at 38.8 per cent in 2011 in Gujarat is slightly better than the national average of 41.1 per cent but well below Maharashtra’s 23.3 per cent.

Similarly, on the infant mortality rate, Gujarat’s figure of 41 per 1,000, though below the national average of 44, is much higher than Maharashtra’s 25 and Tamil Nadu’s 22.

Another disturbing trend has been a falling sex ratio. According to Census 2011, Gujarat’s figure of 918 females to 1,000 males is much below the national average of 940.

Much needs to be done to improve social indicators. There is an awareness now (on the need). But it should have been done much earlier, says Gupta.