A Seshan in New Delhi

"It's a systemic crisis that India is going through." -- Bimal Jalan

As the markets eagerly await the Reserve Bank of India's mid-quarter review of its policy, the controversy over price stability and growth needs to be understood in the proper context.

Economists are fond of using terms from physics to make their discipline look scientific.

The concepts of 'equilibrium', 'velocity', 'acceleration', among others, were thus conceived long ago.

A more recent entry is 'inertia'.

It would mean that the economic system gets stuck at particular levels of economic variables, owing to the absence of forces to disturb the state of equilibrium.

'Inertial inflation' is one such concept.

. . .

India is suffering from inertial inflation

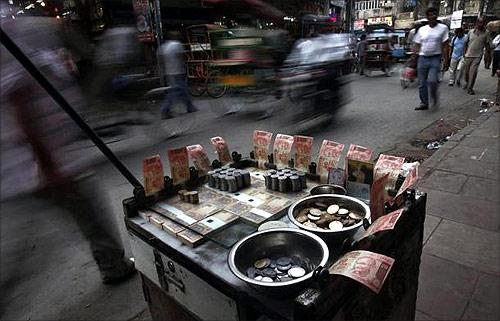

Image: A woman sells drinking water near the Taj Mahal hotel in Mumbai.Photographs: Ahmad Masood/Reuters

It refers to a situation when the rate of price increase attains a stable equilibrium, where it remains until a shock is administered to move it to a new position.

The economics study guide accompanying the economics textbook by Samuelson-Nordhaus says: "The inflation rate itself has some inertia -- that is a tendency not to move unless pushed -- only because prices have a consistent momentum that translates into a stable rate of increase.

Individuals expect it and the expectation tends to become self-fulfiling prophecies.

Either demand-pull or cost-push inflation can contribute to inertial inflation -- the best reflection of which is a simultaneous shifting of both the aggregate supply and the aggregate demand curves."

. . .

India is suffering from inertial inflation

Image: A farmer ploughs his field to sow millet seeds against the backdrop of pre-monsoon clouds at Shapur village in Gujarat.Photographs: Amit Dave/Reuters

The prevailing continuous price rise, more or less at a constant rate, is a good example of inertial inflation.

Inter alia, the factors that contribute to it are the annual increase in support prices for agricultural produce that provide the benchmarks for the markets, the periodical wage revisions in the organised sector and RBI's assumption of an 'acceptable' inflation rate of four to five per cent -- which people know by experience will be exceeded.

The central bank can deal with only the last factor in relation to expectations.

The equilibrium at a high rate seen continuously can be moved down only by a shock to the system, which could be on demand or supply or both sides.

. . .

India is suffering from inertial inflation

Image: Employees affix a bonnet as they work on assembling a Mahindra Bolero vehicle at the company's manufacturing plant on the outskirts of Mumbai.Photographs: Vivek Prakash/Reuters

A demand shock would call for a drastic reduction in the growth rate of money supply from the double-digit levels to single-digit ones.

But that would be unacceptable, since it would lead to a recession in a year that is expecting elections.

On the supply side, considering that food is a major culprit, the government can think of liquidating its enormous grain stocks through free distribution to families below poverty line.

This may be shocking to those who are harping on the fiscal deficit.

But what is the relevance of the fiscal deficit in the context of the wasteful expenditure and scams and scandals that one reads about from time to time?

. . .

India is suffering from inertial inflation

Photographs: Reuters

It is not as if the entire amount of money involved will be a net addition to fiscal deficit for the following reason.

Of the 70 million tonnes of stocks, as of October 1, 2012, only around two-thirds have scientific warehousing facilities -- the rest being left to the mercy of the vagaries of nature under the cover and plinth scheme.

Produce of 2008 vintage are still in the stocks. In Punjab, only three million tonnes of rice and wheat have been covered out of the total of 14 million tonnes.

There is no domestic or foreign market for the rotten produce.

Reports have appeared in the past of the importers of feedlots in the US rejecting our grain being unfit for consumption by cattle.

. . .

India is suffering from inertial inflation

Image: Labourers are silhouetted against the setting sun as they work at the construction site of a residential building in Hyderabad.Photographs: Krishnendu Halder/Reuters

There is a consequential increase in the fiscal deficit in such cases because there is no possibility of recovering even a portion of the purchase price by selling or exporting.

The total quantity of food stocks with the government is nearly three times the buffer stock norm.

The problem will become worse with the current procurement of rice and the one for wheat to start in April.

The suggestion above will not be as bad as it looks if one considers the cost of storage, insurance, interest on borrowed funds, etc, of stocks apart from the value lost owing to the damage to the produce.

The idea will be popular with the government since it will strengthen its vote-bank.

. . .

India is suffering from inertial inflation

Photographs: Parivartan Sharma/Reuters

A committee may be set up to decide on the quantity of free distribution to around 65 million BPL families that can be made without much additional damage to fiscal deficit. Apart from grain, vegetables and fruit have contributed to price rise.

But because of seasonality, their prices may be expected to come down in the near future.

The problem facing the country is structural in all its aspects.

They are political, economic and administrative.

Opening up the retail trade sector or insurance or civil aviation will not make any difference to the more fundamental issues at stake.

How can we accelerate growth if it takes months and years to finalise investment projects, and even longer periods to complete them?

. . .

India is suffering from inertial inflation

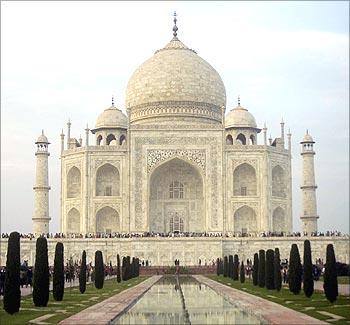

Image: The Taj Mahal.Photographs: Reuters

Bimal Jalan summed up the problem well at a recent panel discussion at the Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research.

To quote him: "We are in the bottom one-third of human development index.

"For me, it is not a question of reforms and economics, which we have and will get. I would say what we need. . . is to do something about the politics and administration of India. It's a systemic crisis that India is going through.

"Nobody can stop India in economic terms, but the system is breaking down."

The author is economic consultant, former Officer-In-Charge, Department of Economic Analysis and Policy, Reserve Bank of India, and Adviser to National Bank of Kyrgyzstan and Bank of Sierra Leone

article