| « Back to article | Print this article |

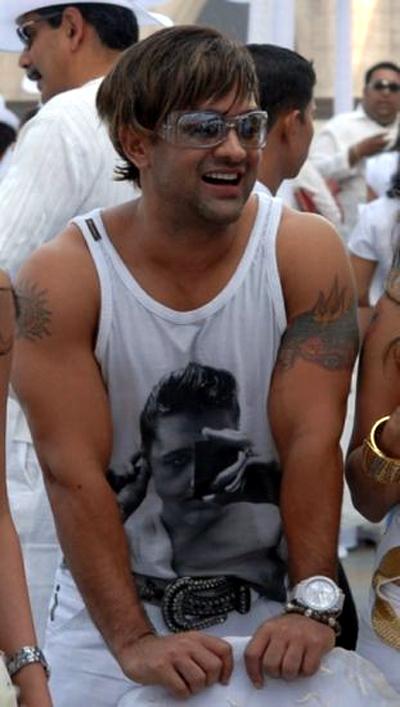

How Yash Birla won one of life's toughest battles

Twenty-two-year-old Yash Birla wakes up at the break of dawn to a phone call that changes his life -- a plane with his parents and sister has just crashed in Bengaluru (then Bangalore).

Leaving his college in North Carolina on a flight to Mumbai, Yash finds out that everything he has known is destroyed and his world is suddenly torn apart.

This is the story of a man who overcomes one of life's toughest hurdles and lives to tell the tale.

On a Prayer by Penguin India is a book on Birla's journey from a state of oblivion to survival, where his deep belief in spirituality and his faith in true love act as a crutch for him to go on.

Here is an excerpt from the book:

.jpg)

Bombay Hospital was near our office at Churchgate.

Sitting in the car, on the way there, I tried to remember M P Birla.

The memories were hazy.

I must have been a kid of twelve or thirteen; we were visiting Calcutta and were going over to his house.

There were three Birla homes in a row, identical on the outside but very different inside. Each one belonged to a different brother.

This was 'bungla number ek'.

A watchman in a thick Bengali accent told us that our host was waiting for us in the garden.

My father and mother had quickly touched the tops of their heads, smoothening their hair out of habit, as they passed through the lobby.

Madhav Prasad, or MP as he was referred to behind his back, was a stickler for short hair.

He hated people who didn't have a cropped haircut and detested moustaches and beards.

As a result everyone around him either oiled their hair till it lay flat on their heads or cut it so short that you could see their scalps.

The servants in the house were the best example of this eccentricity.

But at that age I didn't have a clue.

M P Birla sat on a garden chair and in front of him was a table with a complete tea service laid out on it.

The first thing he said to me was, 'Baal itna lamba nahi rakhte hai, kaato usko.'

His nasal voice and aggressive gesturing got me scared of him immediately.

Snapping back to reality, I wondered what M P Birla would be like now.

The car stopped in the porch of the hospital as I got out of it hesitantly.

A quick elevator ride later I was standing outside M P Birla's suite at the hospital.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

How Yash Birla won one of life's toughest battles

Badi Ma came out and spoke to me in a whisper, 'Woh abhi uth gaye hai. Tum mere saath idhar aao unse milne se pehle. '

She caught me by the arm and dragged me to a private loo outside his room.

There she put the tap on and cupped her hands under the flowing water.

With a quick movement she dropped the handful on the top of my head and gave me a comb from her bag.

I was to comb my hair back, slicked wet.

It looked terrible.

But I agreed to whatever she wanted.

With water dripping down the back of my shirt I entered MP Birla's room.

The air conditioning was on high and it made me shudder.

Propped up by cushions he was sitting upright on his bed.

MP didn't react much on seeing me.

He had partially lost his speech and was only understandable to his wife.

I folded my hands and bowed before him.

He nodded, only slightly.

After a brief introduction Badi Ma asked me to sit on a chair that was placed next to the bed specially for me.

In as soft a voice as she could muster Badi Ma told MP about my predicament and our conversation at home about taking managerial help from her company.

'Hume Yash ki madat karni chahiye, aap kya bolte ho?' she said, looking at him intently. M P slowly turned his head towards her, his eyes looking far away at something else.

I couldn't make out what he mumbled, but Badi Ma nodded her head as though she understood everything perfectly.

It was decided.

They were on board with the plan.

I felt like the couple had just bestowed a huge favour on me.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

How Yash Birla won one of life's toughest battles

After he'd finished his brief instructions, Badi Ma turned to me.

'Agar hum tumhare paas aayenge to tumhe Aditya ko bolna padega ki unki zaroorat nahi hai, 'she said solemnly.

I knew it was inevitable, and didn't need to be told this, so it came as a surprise-as if she just wanted to make sure that I'd follow through and wouldn't expect the two companies to ever work together in helping me.

I agreed.

With a smile on her face Badi Ma walked over to me and cupped my face in her hands. Smiling, she blessed me with a quick pat on the top of my head and that was that.

I walked out with mixed emotions.

Was this the best thing to do? I didn't know, but I went along with it.

Asha bua certainly seemed to think it was, so who was I to disagree?

The next day at the office I walked over to Adit chacha's room.

He was sitting with a stack of papers before him, which he was going over carefully.

When he saw me walk in he smiled and set them down.

The news of my decision was taken well.

He didn't have any complaints or reservations; instead, he agreed that it was probably the best decision for the time being.

I was relieved.

When I walked out, I left with a feeling that I'd done the right thing.

This was the best move, I kept telling myself

The transition from Adit chacha's management to MP Birla's was a smooth one.

No one complained and there was no noise made about the change.

Since she was a housewife, Badi Ma had learnt everything she knew about business from a set of trusted lieutenants.

She had been thrust into managing her husband's companies and didn't know much about business.

With her husband ill, Badi Ma had learnt all this from a man called V D Jain.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

How Yash Birla won one of life's toughest battles

From a completely old-fashioned school of thought, Jain handled M P Birla's businesses like a dictator ran a country.

I was scared of him: Badi Ma gave him too much respect, so I was expected to do the same.

On his first day in my office, V D Jain ran through the list of companies we had.

I sat quietly in front of him while his eyes scanned the papers.

Sheets of financial information sat next to him and he'd pick up some of them when he wanted to see how the company was doing.

‘Yeh company tum ek rupe ke bhaav mein bech sakte ho,’ he said sarcastically, pointing at one of the entries on the list.

It hurt to hear him talk like that, but I stayed mum.

He spoke down to me like I was a school kid and I went along with it.

'Tumhe Jainji ka aadar karna chahiye,' I remembered Badi Ma saying. 'Tum unko dhanyawaad do jab woh tumhara kaam karte hai, 'she had added.

I didn't like all this formal stuff.

My father had never insisted on it, so for me to now thank Jain every day for his help in running the business was a little strange.

I went along without much complaining nonetheless, secretly dreading the time I had to spend with him.

The other man who came from M P Birla's company was J R Birla.

He wasn't related to us, even though we shared the same surname.

Easy to get along with, he was a man of very few words, mild-mannered and accommodating.

He was given the task of teaching me about the cement industry, since he'd handled that sector of the M P Birla organization and had vast experience in the field.

He would come down twice a week to my office and tell me all about sourcing, manufacturing and the nitty-gritty behind a cement factory.

J R was the antithesis of Jain-younger than him and someone I could deal with more amicably.

The office became a lot more different with MP.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

How Yash Birla won one of life's toughest battles

Birla's team now swarming in and out.

I noticed this when my finance head came to me one day.

Scratching his head, he confessed that he didn't have any idea about whom he was expected to report to.

I calmed him down and told him things would be fine.

'Every organization has a time when it goes through changes.

‘We just need to adjust to ours,' I said pensively.

He still looked confused but bought my explanation and walked out of the room.

A few days later I told Asha bua that I wanted Badi Ma to meet Avanti.

‘Dheere, dheere, Yash, dheere, dheere, ' is all she said in reply.

I could see the cogs in her head working.

She would handle this in her own way.

She just needed time.

But to me, time was something I didn't have.

Alone at Birla House, I was tormented by the memories of my family.

I remembered the parties, my childhood, seeing my mother during her Gita paath, my father in his den, Sujata sneaking out to go to a movie with her friends.

I couldn't take the loneliness.

It was driving me mad.

I had too many questions in my head and just wasn't able to let go of my family.

Images of the crash site came back to my mind.

Against everyone's wishes I had gone to Bangalore to see what the wreckage had looked like.

The plane was scattered like the giant carcass of a bird across the golf range where it had crashed.

Debris sat on the grass as forensic teams combed the area for material.

People's clothes and bags were strewn all over the area.

In some places I saw dried blood on the ground. I shuddered to think of what had happened there.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

How Yash Birla won one of life's toughest battles

Witnesses to the crash had told me about seeing my mother.

She was in the front of the plane with my family.

Everyone there had died on impact, many succumbing to the flames that surrounded them and others from inhaling the smoke that arose once all that jet fuel caught fire.

My mother had survived.

She had had the courage to find her way out of the debris and the burning plane.

A man with a camera had taken a picture of her jumping off.

I didn't want to see it.

I couldn't bring myself to see her in that state.

She had collapsed a few feet away from the wreckage.

By the time the ambulance had come to her and taken her to a municipal hospital she had passed away.

The smoke inhalation had killed her.

When I heard the story I couldn't help but think what it would have been like if she hadn't breathed in those fumes, what if she had been taken to a better hospital, faster, I just couldn't know.

Alone at night I would play out the scene in my head.

I imagined them sitting in their seats-the turbulence, their holding hands as the plane started to hurtle to the ground, the impact, the fire, the smoke . . . then nothing.

It was with these thoughts that I went to sleep every night for several months.

Nothing mattered to me more than trying to find an answer to where my parents had gone.

My search turned into an obsession.

I visited a clairvoyant who made up answers to my questions as she went along.

I could make out she was lying.

A book by a lady who had lost her son intrigued me, so I went to meet her and ask her questions about the afterlife.

What I wanted to know still went unanswered.

The need for closure became too much and people soon started sympathizing with me.

In my mind there was definitely something more that I could do.

One last chance to say goodbye to them-that's all I wanted.

Once, while I was sitting at home, my cousin Anu called me up on the phone. 'Guddu, go to this lady who lives in Goregaon.

‘I've heard she uses an Ouija board to get people to talk to their ancestors.

‘It's worth a shot,' she said.

Anu was one of the few people I had shared all my feelings with.

Desperate for anything meaningful, I convinced her to come with me.

Anu agreed and the next day we got in a car and made our way to the old lady.

The driver took an hour to find the exact address.

The neighbourhood was poor and mostly consisted of huts with tin roofs.

The gutters were open and stray dogs roamed the streets in packs.

Walking through the narrow lanes, Anu kept asking people about Mrs Rishi, 'Unka ghar kahan hai?' Not everyone knew who this lady was but we walked on.

After a few clues we finally got to our destination.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

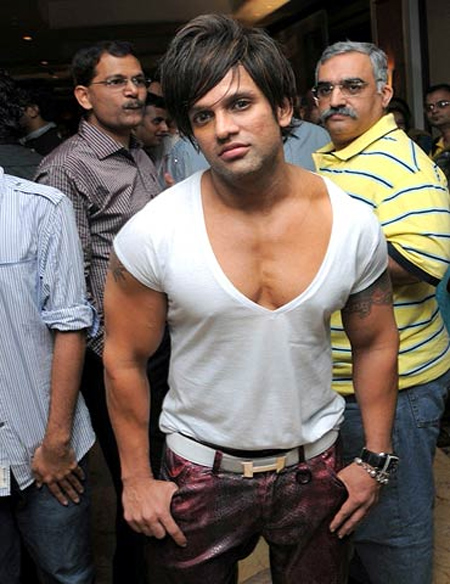

The image has been used for representational purpose only

How Yash Birla won one of life's toughest battles

Anu had called ahead and told a man that we would be coming.

He had been vague on the phone but had agreed in the end. I thought he must've been the lady's son or brother.

The house was tiny.

I stood outside and looked at it from all angles before I banged on the door.

A few seconds later it was opened by a lady who was easily ninety-five.

Her face was wrinkled and darkened by the sun; it almost looked like a sheet of leather that had been forgotten outside.

‘Kya hai?’ she asked us, looking at me from top to bottom.

'Humne aap ke saath ek appointment liya tha aaj ke liye, 'I answered.

'Ek minute,' she replied and shut the door on us.

We didn't know what to do.

Several minutes passed, as we stood waiting outside, before I decided to bang on the door again.

‘This is going to go nowhere,’ I said to Anu, who just patted my back and told me to be patient.

The lady opened her door for the second time.

She had forgotten who we were. 'Kya hai?' she said again.

After I explained to her that I had come for a seance, she finally relented and let me in, quickly shutting the door behind me so no one else could come.

The place was dark and there was barely any furniture.

A bed lay at one end of the room with two chairs next to it.

She walked to them at a glacial pace and pulled one up for me to sit on.

Taking the other one for herself, she opened an antique Ouija board and set it between us. It had a big YES and a NO painted on it, numbers from one to ten and the twenty-six letters of the alphabet from A to Z.

The only source of light was a window with stained glass panes on it.

Blue, red, green.

A few of the panes were missing, allowing streams of sunlight to come in.

She had neither lights nor a working fan.

A bedside fan sat on the floor, but from the looks of it there was no chance that it was in working condition.

She put her finger on an old pointer and asked me to close my eyes and think of the person I wanted to talk to.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

How Yash Birla won one of life's toughest battles

I thought of Mama.

'Kya tum yaha ho?' the old lady asked. ‘Agar ho to table hilao.'

And the table literally tilted and rocked.

The noise it made startled me. There was no way Mrs Rishi could have done it from where she was sitting. I was hooked.

She then asked the person to spell the name they had been given when they were alive. Questions ran through my head.

Does she know who I am?

Has Anu briefed her about me? Has she read the papers?

It didn't make sense.

There was no way this century-old Maharashtrian woman could have known who I was. My face had not been in the media; Anu hadn't known too much about her; and from the looks of it this lady wasn't even expecting to see anybody today.

Her hands started moving quickly on the board.

S-U-N-A-N-D-A the pointer spelled.

My skin broke into goosebumps, with all the hair on my arms standing up.

The old lady told me to ask what I wanted to know.

'Are you okay?' I said.

I was intrigued with what had happened to them in the end. It was painful to think about that.

One of the first things I'd asked for when I'd returned to Bombay was to see the bodies which were at the hospital. My relatives wouldn't let me.

The lady then spelt out: 'Don't ask. We are fine; your sister is still not okay.'

Click NEXT to read further. . .

How Yash Birla won one of life's toughest battles

Then her hands started moving pretty fast and suddenly it all came in one go.

'We were with you this morning. Thank you for the flowers and the mantras,' it spelt out. We'd had a shraadh at home that morning with a pandit performing the pujas; there was no way this lady could have known about it so quickly.

I was reassured.

My sitting with Mrs Rishi went on for a little over an hour.

In that time Anu had gone back to the car and was waiting for me to come back.

I asked all the questions that had come to my mind.

The answers were sharp, crisp and, to me, genuinely from my mother.

I cried.

Warm tears streaked down my face as I carried on.

The questions that had plagued me since the accident all came back.

In the end I was satisfied.

A weight that I had carried on my shoulders was suddenly lifted.

The closure that I had been looking for was now finally in sight.

Things became clear.

There was a life ahead, a life without my family, one where I had to carve out my own destiny.

As time went by I realized that everything I was looking for was already in me -- the answers were simple.

My religion had taught me that -- the Puranas, the japs, the paaths, the mantras.

My grandmother's stories from the Ramayana and the Gita came back to me.

The key to peace was spirituality something I found within me.

I vowed to get to know more about it, explore it and understand the many facets it had, and thus began a lifelong fascination with spirituality.

‘Asha, woh to Marwari nahi hai. Woh humare parivaar mein kaise settle hogi?' Badi Ma said to Bua.

It was the same question my mother had put to me when I had told her about Avanti.

I'd expected this reaction, but was determined to make my own decision this time.

The conversations went on for hours as Mrs M P Birla sat with her head bowed, deep in thought.

The decision was a tough one, but she knew that it would make me happy.

I think at that point no one really wanted to deny me anything that could take away my sadness.

And so they relented.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

How Yash Birla won one of life's toughest battles

I met Avanti at her sister Vaishali's house in Oyster building in Navy Nagar.

We sat on the balcony while Vaishali made some small talk, both of us impatient to get some alone time as we watched the sun go down.

When she left, I finally mustered the courage to tell Avanti the news.

A year had gone by and it was time for us to get married.

She looked confused. I don't think she imagined I'd want to settle down so soon.

The accident was still fresh in my mind, but to me this was the only way I knew how to move forward.

I wanted to start a new family and this was the woman I loved. Avanti went along with the news.

She knew she had a lot of responsibility coming her way; she was going to become a Marwari bahu and that meant she had to change.

The clothes she wore, her demeanour, her hair, her posture, what she spoke -- everything was going to be under scrutiny and so had to change.

At least she thought of it like that. I couldn't have cared less. As long as Avanti and I were together, it was all good for me.

Badi Ma started getting everything ready for the wedding pretty soon.

She took it upon herself to take care of the arrangements, the venue and the food.

It all had to be done according to her way.

I looked at my wedding card and the names of all the family members on it.

This wouldn't have been so if my family were alive.

I missed them in that moment more than I ever had.

We didn't want to go overboard with the celebrations so the wedding was low-key. Guests came to Mahalakshmi where we had the event and then to my house where Badi Ma held a reception.

Dressed in a Marwari sari, Avanti looked like a shy bride who felt out of place.

She had her head bowed down most of the time.

I wore a sherwani that Abu-Sandeep had made for me and greeted everyone who came up with as much of a smile as I could muster.

It was done.

People had accepted her, although reluctantly.

To Badi Ma, we were now an offshoot of her own family.

She wanted Avanti to get to know M P Birla better.

And so we travelled to Allahabad. This is where Badi Ma would take M P when he had memory lapses.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

How Yash Birla won one of life's toughest battles

The home sat on the banks of the Ganga and it felt surreal just being there. Sitting on a mudda I looked at M P Birla sleeping, a pandit read the scriptures to him, while Badi Ma sat in silence with a string of beads in her hand as she did her jap.

Avanti was by her side, trying as hard as she could to read a copy of the Gita she had put in front of her.

The voice of the pandit echoed around us and mixed with the gurgling sound of water from the river.

I took a moment to just look around.

I wanted this -- a home near the river, somewhere spiritual to come to, where all the worries of Bombay could be done away with.

The next day I got a call from work that made us change our plans.

We had to rush back.

With mixed feelings I left Allahabad, promising myself to come back when I had more free time.

Things were getting tough at the office.

V D Jain had brought in a new set of changes to our accounts that everyone was complaining about.

One of the men had gathered the courage to come up to me and tell me about it.

Deflated and confused, I just looked back at him.

I didn't know what to do. 'Please, sir, aapko kuch karna hi padega,' he said as earnestly as he could. I nodded and told him I'd speak to him later.

I knew the problem was V D Jain.

My father had constructed a company where people worked in a different way; there was room for dialogue, accountability was shared by everyone and decisions were taken keeping all factors in mind.

Jain's way of functioning was different.

It was his way or the highway.

The employees were finding it difficult to adjust to that -- he'd bite their heads off when they objected and I was only too aware of this. In the face of this problem, I had to make a decision.

Do I go along with Badi Ma's right-hand man and lose face in front of the employees, or do I work towards change and get someone else?

It was too great a decision for me to make.

I racked my brain over it for hours and spoke to Avanti about it as well.

'Go with your gut, Yash,' she said to me at home. And so I did. Picking up the phone I called Mrs M P Birla in Calcutta.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

How Yash Birla won one of life's toughest battles

After the necessary pleasantries I got to the point: 'Kya hum J R Birla ko nahi la sakte aadhi companies ka dhyaan rakhne ke liye?'

She paused at the other end.

She hadn't expected me to be so blunt.

J R Birla handled a very large part of her businesses and I had got to know him well after all our sessions of sitting together and talking about cement.

'Yeh nahi ho sakta, Yash, unki banti nahi hai, , she replied, referring to J R Birla and V D Jain.

M P Birla's company was run with a clear divide-and-rule philosophy and the two senior-most managers distrusted each other.

Splitting half my companies between them would once again cause friction. I knew this but wasn't in any mood to relent.

I pressed on -- Jain had to go. 'Babaji se tumhe poochhna padega,' she concluded when she saw that I was not going to give in.

This was her way of stalling.

I knew Babaji was in no condition to make a decision either way, but I went along.

I told her I would fly to Calcutta the next day and ask him myself, to which Badi Ma agreed.

She hadn't expected me to be so strongly opinionated about this.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

How Yash Birla won one of life's toughest battles

With our tickets booked, Avanti and I travelled to Calcutta.

We were staying with Badi Ma at bungla number ek.

Babaji was meant to meet us for tea that day.

This was the first time I was coming to their home in Calcutta with Avanti.

They had called elders from the other families as well to meet us, and they were meant to join us after Babaji and I had had our chat.

Wearing the simplest sari she had, Avanti tied her hair into a ponytail.

It was just how Badi Ma liked her to look.

She had taken to the Marwari bahu way of life better than I had expected.

On the outside Avanti looked more Marwari than I did.

'You can't wear that,' she said, looking at me putting on a shirt over a pair of jeans.

'Baah,' I groaned in protest.

Rushing to the cupboard, Avanti took out a neatly ironed cotton pajama kurta.

It was severely starched and I was in no mood to wear it.

After a brief brouhaha on the subject I gave in.

She was probably right.

It was best not to upset anyone right now.

Avanti handed over a vest to me, before I put on the cotton pajamas.

Shaking my head in disapproval, I wore it along with the rest.

It was hot and humid, but nonetheless this was how I was expected to be dressed.

When we walked down the staircase, I could hear Badi Ma shouting orders to the servants.

She was getting everything readied.

Avanti rushed over to her and touched her feet; I did the same.

'Aao, aao, Babaji tumhara intazaar kar rahe hai, 'she said, guiding us to the garden. Memories of the place came flooding back to me.

I remembered my parents and a younger M P Birla who had shouted at me for having long hair, all those years ago.

Two cane chairs had been put in front of him in the garden.

I sat on one and Badi Ma took the other.

Avanti wasn't expected to be a part of this conversation so she took a seat a little farther away.

We were alone except for the few servants who were setting up the tea service. Shakarpara, chivda, poha and masala chai were set out on a table nearby.

Looking inside I could see the European paintings, oriental rugs and Japanese urns in the drawing room.

Their obsession with all things classical from the West was apparent.

It confused me to think why I couldn't wear a T-shirt if they could make their house look like it had been transported from an English country estate.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

How Yash Birla won one of life's toughest battles

'Yash chahta hai ki Jainji aur J R Birla uski company ko aadha aadha samhale,' Badi Ma whispered, going near Babaji.

He shook his head in disagreement and mumbled something I couldn't make out.

'Mumkin nahi hai, Yash, 'Badi Ma translated.

She went back and forth with him.

This scene had become one that I had got used to.

It was Badi Ma's way of saying that Babaji was in charge.

I think in the end the charade fooled no one.

This was her way of showing to the world that the 'man' was still running things.

No one could question the system if the chairman was still making the decisions, regardless of his meningitis, his regular memory lapses and the fact that the only one who could interpret his voice was his wife.

The conversation eventually concluded with the decision that I had to choose one person. It was either V D Jain or J R Birla.

I couldn't have them both.

I chose J R.

Badi Ma sighed a defeated breath of air when she heard my answer and then tilted her head.

'Okay, so be it,' she would have said if she had been inclined to voice her thoughts.

Just then the first guests of the evening came in.

And then the others followed, right on time.

Everyone was in their seventies: chairmen of their own companies, with their wives, some Birlas, others from different prominent Marwari families.

They had come to see the son of Ashok Birla, the grand-nephew of M P Birla and the great-grandson of Rameshwar Das Birla.

I felt like I was a mannequin on display.

Avanti touched their feet without knowing who they were.

The women were impressed but somewhere still behaved like she wasn't one of them. Sipping their tea from dainty cups with biscuits and chivda on the side, the old men talked business-cement, jute, steel, the government, taxes, export and import, everything was being discussed.

The only one staying quiet was Babaji whose eyes darted from one person to another as a servant stood next to him with a teacup in his hand, making him sip from it at short intervals.

I tried my best to blend in.

The stuff I had picked up from J R Birla about the cement industry helped me a lot.

When they'd heard me make my point the old men nodded in unison.

I had got their approval.

Ashok's son was okay.

All was not doomed for this company.

They looked at each other and silently conveyed this, almost telepathically.

I heaved a sigh of relief and for a brief second almost felt a part of their world.