| « Back to article | Print this article |

Scams, controversies: Why are scientists quiet?

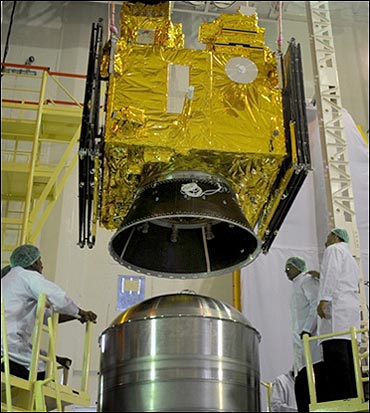

I suspect Indian scientists have retired hurt to the pavilion. They were exposed to some nasty public scrutiny on a deal made by a premier science research establishment, Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), with Devas, a private company, on the allocation of spectrum.

The public verdict was that the arrangement was a scandal; public resources had been given away for a song. The government, already scam-bruised, hastily scrapped the contract.

Since then there has been dead silence among the powerful scientific leaders of the country, with one exception. Kiran Karnik, a former employee of ISRO and board member of Devas, spoke out and explained it is wrong to equate this deal with the scam of mobile telephony.

Click NEXT to read on

Scams, controversies: Why are scientists quiet?

Clearly, there is much more to this story. But when the scientists who understand the issue are not prepared to engage with the public, there can be little informed discussion.

The cynical public, which sees scams tumble out each day, believes easily that everybody is a crook. But, as I said, the country's top scientists have withdrawn further into their comfort holes, their opinion frozen in contempt that Indian society is scientifically illiterate.

Click NEXT to read on

Scams, controversies: Why are scientists quiet?

This is not good. Science is about everyday policy. It needs to be understood and for this it needs to be discussed and deliberated openly and strenuously. But how will this happen if one side - the one with information, knowledge and power - will not engage in public discourse?

Take the issue of genetically-modified (GM) crops. For long this matter has been decided inside closed-door committee rooms, where scientists are comforted by the fact that their decisions will not be challenged. Their defence is "sound science" and "superior knowledge".

Click NEXT to read on

Scams, controversies: Why are scientists quiet?

Silence is the best insurance. This is what happened inside a stuffy committee room, where scientists sat to give permission to Mahyco-Monsanto to grow genetically-modified brinjal.

This case involved a vegetable we all eat. This was a matter of science we had the right to know about and to decide upon. The issue made headlines.

The reaction of the scientific fraternity was predictable and obnoxious. They resented the questions. They did not want a public debate.Click NEXT to read on

Scams, controversies: Why are scientists quiet?

Finally, when environment minister Jairam Ramesh took the decision on the side of the ordinary vegetable eater, unconvinced by the validity of the scientific data to justify no-harm, scientists were missing in their public reactions.

Instead, they whispered about lack of "sound science" in the decision inside committees.

The matter did not end there.

Click NEXT to read on

Scams, controversies: Why are scientists quiet?

The report released by this committee was shoddy to say the least. It contained no references or attributions and not a single citation.

It made sweeping statements and lifted passages from a government newsletter and even from global biotech industry. The report was thrashed. Scientists again withdrew into offended silence.

Click NEXT to read on

Scams, controversies: Why are scientists quiet?

The report is only a cover for their established opinion about the 'truth' of Bt-brinjal. Science for them is certainly not a matter of enquiry, critique or even dissent.

But the world has changed. No longer is this report meant only for top political and policy leaders, who would be overwhelmed by the weight of the matter, the language and the expert knowledge of the writer.

Click NEXT to read on

Scams, controversies: Why are scientists quiet?

This is the difference between the manufactured comfortable world of science behind closed doors and the noisy messy world outside. It is clear to me that Indian scientists need confidence to creatively engage in public concerns.

The task to build scientific literacy will not happen without their engagement and their tolerance for dissent.

The role of science in Indian democracy is being revisited with a new intensity. The only problem is that the key players are missing in action.