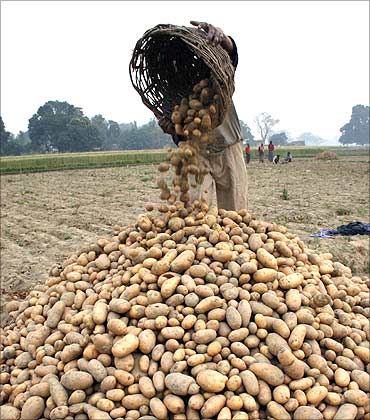

Photographs: Reuters Shonalee Biswas

The latest round inflation numbers shows that the price of milk, pulses, egg, fish and meat has gone up and that of vegetables has fallen.

But there are some fundamental reasons which will ensure that prices of vegetables and other food stuff will continue to go up in the near future, despite the politicians saying otherwise.

The first and the foremost reason for it is the Japan syndrome.

So what is the Japan syndrome?

This term -- Japan syndrome -- has been coined by environmentalist Lester Brown. In his book Outgrowing The Earth, he writes: 'As a country industrialises and modernises, crop land is used for industrial and residential development. As automobile ownership spreads, the construction of roads, highways, and parking lots . . . takes valuable land away from agriculture . . . Secondly, as rapid industrialisation pulls labour out of the countryside, it often leads to less double cropping, a practice that depends on quickly harvesting one grain crop once it's ripe and immediately preparing the seedbed for the next crop.'

. . .

Here's why your food bill will continue to go up

Photographs: Reuters

The syndrome is so called because it was first observed in Japan in the mid- and the late-1950s. Since then it has been seen in other densely populated countries like Taiwan, South Korea and, for the last decade-and-a-half, even in China.

As Indian cities expand what they are taking away is basically agriculture land. With lesser land, the produce comes down and of course that means higher prices for food stuff.

Rapid industrialisation

Of course, industrialisation is the other worry, especially in smaller states like West Bengal where land is a problem.

So, every time the government takes away land and gives it to an industrialist, it is essentially taking away what is primarily agriculture land.

. . .

Here's why your food bill will continue to go up

Photographs: Reuters

Other than denying the farmer a right to earn an income (unless the industry that is established gives him a job) it also means lesser land for growing food.

Just what Lester Brown points out in his book.

More money in the hands of the farmer

The current United Progressive Alliance government has been very friendly to rural India. Other than writing off agriculture debt of around Rs 70,000 crore (Rs 700 billion) a few years back, it has also launched guaranteed income schemes like the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme.

This has led to rural incomes going up. A recent report -- titled The Time is Ripe -- brought out by Kotak Institutional Equities points out that rural income in India has risen by 138 per cent to Rs 6,81,400 crore Rs 6,814 billion) over the five years ending 2009.

. . .

Here's why your food bill will continue to go up

Photographs: Reuters

And how does that impact food prices? With more money in the hands of rural India, eating habits seemed to have improved. As Brown writes: 'As incomes rise, diets diversify, generating demand for more fruits and vegetables.'

Studies carried by economists suggest that once the per capita income of a country goes beyond $1,000 per year (the per capita income in India is around $1,260 year) people move from cereal-based diets (rice, wheat, maize, etc) to protein-based diets (dal, non-vegetarian food).

India is primarily a vegetarian nation, which means there would be increased consumption of dal and also milk. And that explains why dal, milk and even egg prices (which a lot of vegetarians have started to consume these days) will continue to go up.

Over-pumping groundwater

This is another serious issue that will lead to food prices going up in the days to come. Studies carried out by the World Bank indicate that nearly 17.5 crore (175 million) people in India are being fed by over-pumping aquifers (underground water).

. . .

Here's why your food bill will continue to go up

Photographs: Reuters

A report brought out by DWS Investment points out: 'Dramatic increases in the irrigation of crops across northern India have substantially depleted the region's groundwater. Between April 2002 and August 2008, aquifers lost a total of more than 54 cubic kilometres per year. That decrease in groundwater is even more than double the capacity of India's largest reservoir. This would mean lesser water for irrigation across the Gangetic plain which produces a major part of the grain that India consumes.'

Rising temperatures

Rising temperature is a concern as well where the production of wheat and rice is concerned. As Brown writes: 'The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change projects that the temperature will rise by up to 6 C (11 F) during this century. This would mean glaciers melting at a faster rate. It is the ice melt from glaciers in the Himalayas that sustains the major rivers of India and the irrigation systems that depend on them, during the dry season... Indeed, the projected melting of the glaciers... presents the most massive threat to food security humanity has ever faced."

India is the second-largest producer of wheat and rice in the world; the largest being China.

. . .

Here's why your food bill will continue to go up

Photographs: Reuters

Agri commodities and the price of oil

Also, these days the price of some commodities like corn and sugar depends on the price of oil.

Take a country like Brazil. Brazil has a lot of cars that run on ethanol. This ethanol is made out of sugarcane. So if the price of oil goes up, the choice of ethanol as an alternate fuel also goes up.

This in turn leads to the price of sugarcane that is used to make ethanol to go up. With sugarcane being expensive, sugar cannot be cheap.

In the United States, corn is used to make ethanol. So if oil prices go up, corn prices also go up.

Given these reasons, Indians should be ready to pay more for their food in the days to come.

The author can be reached at shonalee.biswas@gmail.com

article