| « Back to article | Print this article |

Mumbai airport: It's growth versus slum-dwellers!

The round-the-clock noise of hammer on steel keeps Shobha Madye's nerves steady.

She lives in a shanty at Sahar village, close to the under-construction elevated road that will connect the Western Express Highway with Chhattrapati Shivaji International Airport in Mumbai.

Madye knows that she will have to move out the day the road is completed and the noisy site falls silent.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Mumbai airport: It's growth versus slum-dwellers!

The financial consequences could be dire: she runs a tuition class for 40 students in her one-room set-up, her husband is a driver with a private agency close by, and both her children are enrolled in schools nearby.

"Why would we want to move to Kurla or Bhandup? We have been living here since 1975. We have to start our life from zero wherever we go," says the feisty woman. Thanks, but no thanks.

Madye lines up two of her students, Sunil and Sanjay, who work as domestic hands in homes nearby, to enforce her viewpoint.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Mumbai airport: It's growth versus slum-dwellers!

"It will be hard for people like them to find a source of living if they are shifted elsewhere. And if they move there they will have to spend money in travelling from there to their workplace here," Madye says.

Is her angst genuine? Or does she see this as a good opportunity to make some money? The only thing that could make her move is money, she says, and that too Rs 2.5 crore (Rs 25 million).

The 275 acres of land occupied by the 85,000 or so slum dwellers of Sahar is vital for the modernisation and expansion of the Mumbai airport (which since 2006 is owned by a GVK-led consortium).

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Mumbai airport: It's growth versus slum-dwellers!

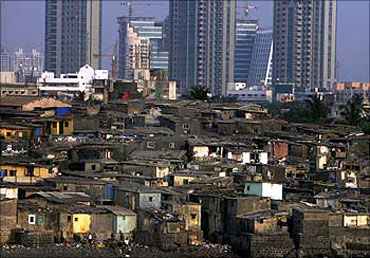

Runways, taxiways, hangars, terminals, roads, offices, et cetera need to be built. But there is no land to do that on. The airport, which offers many overseas travellers their first impression of India, is choked by slums on several sides, and Sahar is the largest of them.

The use for the Sahar acres has not yet been specified, but it is a 'vital public project' according to the government of Maharashtra.

Housing Development Infrastructure Ltd got the mandate to relocate slum dwellers to newly built homes elsewhere in Mumbai. These houses will be given absolutely free.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Mumbai airport: It's growth versus slum-dwellers!

In return, HDIL will be entitled to development rights within the airport. In the last two years, it has received rights to 10-11 million sq ft.

The first complex of 7,800 houses at Premier Compound Kurla is ready, and HDIL has handed over 300 house keys to the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority.

So far, however, only 55 families have moved in, even though these are modern 1BHK houses of 269 sq ft each, with clean surroundings, round-the-clock power and water supply, and a sewage treatment plant.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Mumbai airport: It's growth versus slum-dwellers!

Most people of Sahar are unwilling to move. One reason is the trauma of relocation that Madya and others fear. The other is that as many as 40 per cent of the slum dwellers are not eligible for new houses.

The Supreme Court has said that only those who purchased or built a house at Sahar before January 1, 2000, will get the new houses. Others have to fend for themselves, and are therefore bitterly opposed to the project.

As a result, MMRDA has had to twice put off its survey to count those who are eligible. When its surveyors finally visited Sahar, they found the residents standing vigil at the entrance of the slum.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Mumbai airport: It's growth versus slum-dwellers!

The moment they entered the village, bells started ringing in temples and churches, and the mosque called the faithful to prayer.

Letters were sent to heads of state of other countries, signed by 10,000 slum dwellers, saying that Christianity is in danger at Sahar since the 'government wants to destroy the 409-year-old church' located here.

Even now, the residents show no sign of giving up without a fight. "Most of the people in this area have purchased houses in the last 11 years," says Santosh Bane, a resident.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Mumbai airport: It's growth versus slum-dwellers!

"I bought my house in 2001 from someone who was staying here since 1970. Since 2002, I've cast six votes including in BMC [Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation], state and general elections. After voting six times I've been declared ineligible by the government. It means my votes were legal but my house and I are not."

Aadesh Hadkar, on the other hand, is in danger of not being rehabilitated because he was careless while severing ties with his former wife.

The couple separated in 1999, and Hadkar lost possession of the house he had shared with her. Thereafter he moved into a house (also built before 2000) that he owns just down the lane. He diligently did everything he could to erase the link with his ex-wife. Or so he thought.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Mumbai airport: It's growth versus slum-dwellers!

Hadkar applied for a new ration card and electricity bill, but 'didn't consider it the need of the hour' to have a separate voter card made. Now Hadkar has been informed that rehabilitating his former wife is equivalent to rehabilitating him; going by the evidence of a common voter card after all, he is still married to her.

Hadkar is filing a petition in the civil court to prove that he needs a house of his own, because he and his former wife no longer have anything in common.

The original inhabitants of Sahar claim that the British took away their land at gunpoint during the Second World War on the pretext of national defence.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Mumbai airport: It's growth versus slum-dwellers!

When the colonialists left India, they returned to the land and built their houses. Of course, along came migrants and other squatters.

"If the first government of India had erected a barricade with a warning sign to keep off the property then no one would've dared to enter it. But the government didn't care then. Instead, BMC, the cops and politicians, every one of them, took their share of money and overlooked constructions in the area," says Nicholas Almeida, a social activist.

"Now, politicians want us to move for airport beautification. Why should we? Two chief ministers, Ashok Chavan and Vilasrao Deshmukh, had promised that residents will be rehabilitated within the radius of 3 km in accordance with the National Rehabilitation and Resettlement Policy. Are they doing that?"

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Mumbai airport: It's growth versus slum-dwellers!

HDIL vice chairman & managing director Sarang Wadhwan, 33, says it's not binding on the company to provide affected people with homes within 3 km.

The homes just have to be within the Mumbai district. HDIL can use any free land that falls within Greater Mumbai, all the way up to Dahisar, to rehabilitate the slum dwellers.

"We're trying our best to keep them close to the places of their employment so that the cost of movement doesn't increase haphazardly. But not everyone will be shifted into the Kurla property. Only 17,800 tenements are being created there. The balance land is all over the place. If land is available closer to the airport then we'll try to get it for development but people have to realise that there is going to be a change. And change is always -- always -- accompanied by fear."

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Mumbai airport: It's growth versus slum-dwellers!

At the moment, HDIL doesn't have all the land required for resettlement. It hopes to add another 8,000 or so houses by December.

"For the next phase we will require the assistance of the government in providing us land," says Wadhawan. Getting displaced "in a city like Mumbai", Wadhawan understands, "is not a good way ahead".

Experience tells us that slum dwellers find it difficult to live elsewhere -- they miss the old proximity and chaos.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Mumbai airport: It's growth versus slum-dwellers!

In a few earlier rehabilitation projects elsewhere in Mumbai, some people took possession of their new homes, put them under lock and key -- because they cannot sell the new houses for 10 years from the date of possession -- and came back to live in the slums.

The experience of people resettled earlier from the airport site gives the slum dwellers of Sahar little confidence.

In 2005, people were moved from Rafiq Nagar to 2,200 tenements near Goregaon for the expansion of intersecting runways. There was some resistance from the inhabitants but local politicians convinced them.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Mumbai airport: It's growth versus slum-dwellers!

Just four months later, in the resettlement tenements the elevators had stopped working, and the erstwhile slum dwellers realised there were no schools around for their income group.

The drive from Sahar to Premier Compound in Kurla isn't smooth. It gets progressively worse as the bottomless potholes jounce you about in your seat, until you turn a corner to enter the stretch of Kohinoor City on the right-hand side of the road.

Near the main gate, on the third floor, resides Anil Neurittiwal, who moved here in July. He is one of the few who jumped at the chance of living here, because his old place leaked from every corner during the monsoon.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Mumbai airport: It's growth versus slum-dwellers!

And that's why, even though his workplace is far away in Andheri, he shifted without a second thought. "The living standard here is far better," he says. "There, in the rainy season, there would be flooding. Here there is no such problem. I had a 10 ft-by-10 ft room there; so it's more comfortable here. But I miss my friends who have not been able to come due to ineligibility," says Neurittiwal, his final words in a low tone.

What catches Neurittiwal's eye every morning when he pulls back the curtains of his drawing room is a picture of idyllic existence on the other side of the barricade in Kohinoor City.

Does he find this awkward to deal with? Is this another reason why his friends are reluctant to join him? Would he rather stay among his equals in the slum cluster? And is this why Madye says: "We're happy where we are"?