Photographs: Photograph courtesy: Kashish Parpiani Faisal Kidwai in Mumbai

'It is not as if the political class is unaware of the magnitude of the issues India faces,' says Shankkar Aiyar, author of Accidental India: A History of the Nation's Passage through Crisis and Change

'The disconnect is in the politician's belief that it is enough to manage the outrage to get re-elected, that electoral sops rather than long-term solutions is the road to sustain power.'

The major turning points in India's history were not the result of foresight or careful planning, but were rather the accidental consequences of major crises that had to be resolved, Shankkar Aiyar says in his book, Accidental India: A History of the Nation's Passage through Crisis and Change.

Aiyar, who has reported on the political economy of India for more than 30 years, says Indians live in the 21st century while the government is still lost in physical queues, paper trails of triplicates and red tape.

There is a need for a total overhaul of the way the government functions, he tells Rediff.com's Faisal Kidwai in an interview.

You have said that the key decisions made in the country since Independence have not arisen from foresight and planning, but have been the accidental results of crises. What do you mean by this?

India is the only country where change acquires the tag of revolution. So we have the Green Revolution, the Software Revolution, the RTI Revolution, the Telecom Revolution and so on.

Name one other country which deploys the phrase 'liberalisation' in its policy discourse. These changes should have come in the natural course, but they were stalled and then forced by crises.

Every chapter of Accidental India begins with a date. It is intentional, to show how each change in India takes tragically long to arrive, and then to bring about transformation.

Not just in terms of time, but in terms of the trauma and pain millions suffer.

Please ...

'Every transformation in India has come amidst crises'

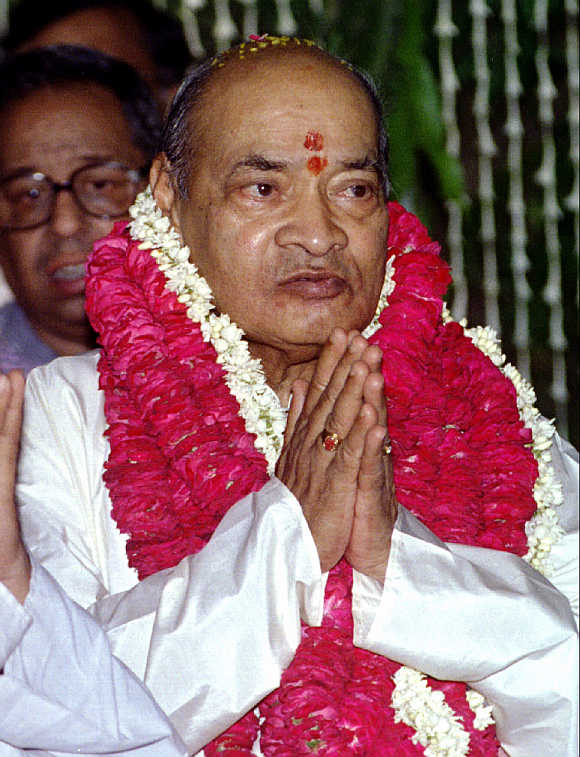

Image: Former prime minister P V Narasimha Rao, the architect of liberalisation.Photographs: Sunil Malhotra/Reuters

It was known by the late 1950s that the Licence Raj was disastrous, yet liberalisation didn't come until 1991 when then prime minister (P V) Narasimha Rao seized the balance of payments crisis to dismantle the Licence Raj which brought in liberalisation.

India suffered the worst of famines and its poverty was located in poor agriculture practices. Yet agriculture did not receive its due until the 1960s when drought, the threat of famine and the shame of being denied food aid and being tagged as the 'ship to mouth economy' enabled the Green Revolution led by C Subramaniam.

It took four decades for India to dismantle the Licence Raj, two decades for the Green Revolution, three decades to realise the competitive edge in software and technology... and each of these game changers came to be only because there was a crisis.

Every transformation in India has come amidst crises, institutional failure and driven by individual courage.

What is dangerous is that the pattern continues. Even in the way the government is addressing the current slowdown and fiscal crisis. It is common knowledge that growth spurs revenues.

It is also known that State intervention for inclusive growth demands resources. These can only be derived from growth. Yet the economist-PM stared at a decline in GDP growth for 24 months.

The government acted only P Chidambaram came back in as finance minister and his presence pointed to the obvious -- the rating agencies had threatened to lower India's rating to 'junk status.'

Please click NEXT to read futher...

'Every transformation in India has come amidst crises'

Image: Tourists take a boat ride amid fog at the Sukhana Lake on a cold winter morning in Chandigarh.Photographs: Ajay Verma/Reuters

Why do we wait for a crisis to carry out major decisions?

In one word, the answer would be: Politics. Change is by definition disruptive, but it is an also imperative for progress.

Disruption dislodges the entrenched, therefore both political parties and bureaucracy resist it.

Politicians view every problem and its solution through the prism of electoral dividends; the bureaucracy accepts what is convenient and does not impact their status quo.

Ergo, the objective of national interest and greater common good is frequently subjugated.

Please ...

'Every transformation in India has come amidst crises'

Image: A French tourist walks past Buddhist religious flags at the Namgyal Tsemo Gompa monastery in Leh.Photographs: Fayaz Kabli/Reuters

You have also said that once the crisis abates, the follow through ends.

This is evident across sectors. Consider the 1991 reforms where the Licence Raj was replaced by the Permission Raj.

Two decades after 1991, India continues to rank at the bottom of global rankings for ease of doing business.

The occurrence of mega scams in itself is evidence that politics controls the purse strings of corporate profitability. Ditto with agriculture.

India adopted technology for agriculture in the 1960s, yet once the crisis of scarcity abated, agriculture went into neglect.

India has the potential to be the food basket of the world, but it requires investment and innovative initiatives.

By 2050 India's population will touch 1,500 million and it will need over 400 million tonnes of foodgrain, but there is no urgency for a strategy to achieve this.

...

'Every transformation in India has come amidst crises'

Image: A fisherman arranges a fishing net as his wife paddles their boat in the waters of the Periyar river, Kerala.Photographs: Reuters

Whether it is economic or social issues, why is the government so bad at pursing a goal to the end?

Policy by definition is meant to transform outcomes by altering the processes that deliver results. The best management policy -- whether in the private sector or in government -- is one based on objectives.

In India governments often craft policy without enough attention to the processes for achieving objectives. The quest seems to be to address the outrage, not the outcomes. It reflects a lack of conviction in the need for transformation.

What is ubiquitous to India is the glaring absence of strategic objectives and result orientation.

India spends close to $100 billion -- between the central and state governments -- on social sector programmes, yet some of our human development indices are worse than sub-Saharan Africa.

There is planning, but no realistic plan to get there, whether it is food or income security.

The difference between success and failure is located in the quality of governance. Yet no government wants to confront the problem of bureaucratic sloth.

It is fairly clear that India needs a charter of governance which defines what its 30 million-plus bureaucracy will deliver.

Successive governments have appointed committees and commissions on structural and administrative reforms. Every report has been binned because of political expediency.

Please ...

'Every transformation in India has come amidst crises'

Image: A game of cricket in Mumbai.Photographs: Danish Siddiqui/Reuters

The government's response and reaction to protests and issues -- whether it is corruption, poverty or the recent gang rape in New Delhi -- is painfully slow.

Do you think there is a deep disconnect between politicians and people?

Government prefers to address the outrage, not the outcomes.

There is little doubt that there is a wide disconnect between politicians and the people.

Private India lives in the 21st century. People are using SMS, IVRS (Interactive Voice Response System) and online solutions for better productivity.

However Public India -- that is the government -- is still lost in physical queues, paper trails of triplicates and red tape.

It is not as if the political class is unaware of the magnitude of the issues India faces.

The disconnect is in the politician's belief that it is enough to manage the outrage to get re-elected, that electoral sops rather than long-term solutions is the road to sustain power.

There is some recognition of the need for responsive systems and for sensitivity.

The tragedy is that the leadership across parties is locked in the mentally-geriatric class lacking the capacity and imagination to address issues.

Please ...

'Every transformation in India has come amidst crises'

Image: Shoppers leave a mall in Mumbai.Photographs: Danish Siddiqui/Reuters

What's the solution to these problems?

There is a need for a total overhaul of the way the government functions.

Systems designed by colonial powers in the 19th century to manage a colony cannot be instruments of change in the 21st century for a nation with ambitions of being a superpower.

The way forward is to construct a citizens' charter of services governments are obliged to provide, list the objectives and restructure the processes of governance.

India needs to induct technology in governance in a big way to provide transparency and address the issue of scale across services.

There is also a need for a new blueprint, a new organogram of governance -- both at the Centre and in the states.

Why should there be a rural development ministry or a water resources ministry both in the states and at the Centre?

People vote governments in the states. But the state governments are frequently unable to deliver change as the financial levers to engineer change are with the Centre.

The ailment afflicts local governance too.

States do to the municipalities and panchayats what the Centre does to them. It is this multiplicity of controls and agencies that is the cause of chaos across the social sector.

If every vote is sacred, then those voted to power must be allowed to succeed or fail.

Democracy must be the ultimate regulator.

article