| « Back to article | Print this article |

India is changing, but for whom?

The rambling transport department office in Bengaluru's Indiranagar, where you go to get your driving licence renewed or get something done for your car registration, arouses mixed feelings.

Its processes appear convoluted, its staff are as perfunctory as those in other sarkari offices, and the queues before many counters are often forbidding.

But on top of this sit several attempts to be citizen-friendly. The reception has many signs making it easy to get started on your business; those at its counter appear helpful; and extensive computerisation of records must have revolutionised data retrieval and the ease of transacting.

My own experience has been instructive. My overall impression -- that in Karnataka if you speak English, look respectable and approach the officer in-charge of a particular section then you can get your work done fast and without paying up -- has been partly shaped by my encounters at this office.

That is how I have been able to get my driver to renew his licence and do the same for myself reasonably smoothly.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

India is changing, but for whom?

So it was with both hope and trepidation (you never know) that I approached the office for a 'no objection' certificate to transfer the registration of my car from Karnataka to West Bengal.

I seemed to be in luck: a kindly man at the counter helped me fill up the form (of course in triplicate). My luck bounced further up several notches thereafter when he took me in tow and did a round of many desks in many halls to take the papers forward.

However, as this progressed, I slowly began to get a bit worried. He couldn't be all that altruistic. Did I look the well-heeled type who would handsomely reward someone who carried his papers personally right through and got the job done pronto?

Then the magic spell ended. He waved a computer printout, addressed to the city police commissioner's office, asking it to certify that the car was not reported in any theft case.

It ended with the reassuring line that if they didn't hear from them (the police) in a month they would issue their certificate without the other certificate. But I can't wait that long, I protested.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

India is changing, but for whom?

The helpful man had an answer to that too: I will use one of my men here to get the paper from the police if you will pay his 'expenses'.

The buck stops here, I thought, and offered to pay him for his and his man's efforts once I got my certificate but not before.

He was not buying that and said I would then have to go myself and get the certificate. The thought of that made me shiver and I mumbled that I would then have to go and meet the top boss of his department, introduce myself as a journalist and ask him to use his discretion to waive the waiting period.

The mention of 'journalist' and my willingness to meet the top boss made him turn distinctly off-colour. He said that what he had done so far for me was nothing and slunk away, not to be seen again.

The big boss was on leave so I went the next day with heroic resolve to try my luck at the hands of the police, whom all normal people dread.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

India is changing, but for whom?

At the police headquarters, I went via a counter called 'single window' to the data department. A friendly young man before a computer, surrounded by ancient steel almirahs told me -- I could hardly believe my ears -- to come back after one o'clock and take the certificate.

I came back and the paper was put in my hands! Even God couldn't give better service, I thought, and laughed to myself that the biggest hurdle in visiting the police had been finding a parking space.

For that I had had to engage in plain deceit. Not allowed to park at the office, I drove to a posh diagnostic centre nearby, handed over the car for valet parking, rode the lift to the second-floor reception like other patients, walked out and over to the police department to submit the letter, came back and sat among the milling crowd at the reception for an hour.

Then I walked to the police office again, came back with the precious paper, touched base at the reception again to behave like other patients, got the car and drove off -- after tipping the driver Rs 10!

Back at the transport office things were not as smooth. By myself this time, without the help of the reception fellow, I journeyed from section to section, at some places was asked to sit, at others curtly told to wait outside.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

India is changing, but for whom?

Once, when the going got particularly tough, a middle-aged man at one of the counters who spoke English well possibly took pity on me and showed exactly where I had to push, gently.

Eventually, at around four, I was able to walk out of the office with a sense of victory, 'no-objection' certificate in hand.

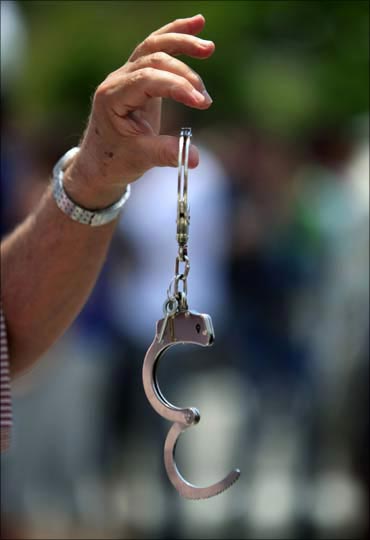

During those two days I saw money change hands, discreetly of course, and an employee looking like a head clerk going from counter to counter distributing cash and ticking names off a list.

There was this highly agitated middle-aged man in the corridor yelling into his phone that he had been asked to pay Rs 5,000 for a form.

And there was this utterly distraught young man saying that the one month was gone and there was no sign of his papers. India is certainly changing -- but for whom, and how fast?