| « Back to article | Print this article |

How Rao is building low-cost, high-quality homes

A new kind of 'social entrepreneur'?

We originally wanted to run the story of Value & Budget Housing Corporation (VBHC) as a case of 'Social Entrepreneurship'.

Indeed, servicing the bottom of the pyramid has been one of the lasting imprints of this past decade, and we thought VBHC was a great way of capturing this.

However, in this exclusive interview to The Smart Manager, Jerry Rao, former CEO of MphasiS and the current chief of VBHC, made us rethink our stance.

Not for him the pedestal of 'social entrepreneur', and he also made it clear that though his company is addressing the base of the pyramid, it is not really hitting the very bottom of it.

This does nothing though to dilute the enormous significance of Rao's new business. Started at the very end of the last decade, VBHC is trying to help the common Indian free herself from the 'stepchild complex' inflicted by pathetic customer service.

And if that is not a massive social end, then 'social entrepreneurship' may well be as hollow a term as Rao would have us believe.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

How Rao is building low-cost, high-quality homes

A straightforward business

Let me begin by clarifying that I am reluctant to take on the halo of a 'social entrepreneur'. I don't understand the term, to be honest.

As far as I am concerned, I am running a for-profit company, selling a product to not the ultra-rich but to the emerging middle class. It is a 'base of the pyramid' product, but not really targeted at the very bottom of the base.

Having said that, I have to admit it has been quite a shift from my corporate days. The fundamental reason I chose to venture into this area is rather straightforward -- there is a significant market for high-quality, low-price residences in this country.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

How Rao is building low-cost, high-quality homes

Just like there was a market for high-quality, low-price detergents when Nirma came in, or for high-quality, inexpensive bicycles when Hero Cycles started out, or indeed just like today when Tata Motors has shown that there is a market for high-quality, low-price cars.

We are still a poor country, our per-capita GDP is still only a thousand dollars. How many million-dollar homes can you sell here?

On the other hand, just as Nirma very quickly became the largest selling detergent in the world in tonnage terms, I think it is obvious that you could sell a lot of homes if you are willing to price them attractively for a larger market rather than for a niche market, as has mostly been the case till now.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

How Rao is building low-cost, high-quality homes

The oldest dilemma in business

There has been a lot of buzz in the recent past about enterprises that appeal to the 'bottom of the pyramid'.

This could be a reflection of one of the oldest dilemmas in business -- whether one should build a mass-market, low-cost product or a niche, 'boutique' product.

It is the same dilemma that Singer sewing machines faced a hundred years back, or Henry Ford did with the Model T, or Karsanbhai Patel faced with Nirma. It is like the Gucci versus Bata debate.

Generally, business-school training teaches you to jack up your price for a small market segment so that you can get high returns.

But Henry Ford, for instance, did exactly the opposite -- he standardised his product and sold more units, even though that meant lower per-unit profit. That's the route our company is taking as well, though it may not be the only valid route.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

How Rao is building low-cost, high-quality homes

Engineering a landslide

The most important element in our strategy is that we do not want to sit on land till its value appreciates too much for the purposes of budget housing.

In other words, quick turnaround is key. The inherent profitability of our project is based not on outrageous land value but on selling more, quicker. We are happy if we can achieve a modest mark-up to our costs.

In that sense, we are more like a manufacturing company. In manufacturing, a 25 per cent return on equity is considered excellent, whereas when it comes to real estate, sometimes there is no stopping a developer even at the 100 per cent mark.

Of course, it is still early days for us, but I do believe that the downsides to our business model are fairly limited. This is not like software: with land, you will almost always recover your investment soon, though you may not make a staggering profit.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

How Rao is building low-cost, high-quality homes

The upsides are not egregious either, but like I said, that's not why we are in this business to begin with.

The other important driver that will get us where we want to be is, of course, innovation.

Innovation not so much in product, save that we are making modest homes and not massive villas, but innovation in processes.

We have to constantly innovate to shorten delivery times, to move our inventory faster. This in turns fuels the larger innovation in the business model itself, which inverts the traditional approach to real estate with a focus on high quality and low costs.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

How Rao is building low-cost, high-quality homes

The weakest link?

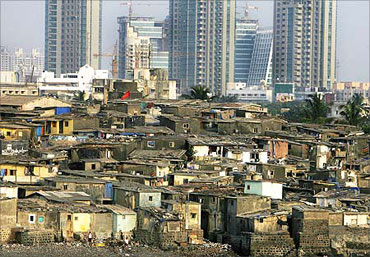

Though there are few downsides to the business model per se, the demand side faces considerable constraints on one crucial count.

Our developments are mostly located on the outskirts of cities for obvious reasons, hence the buyers have to commute long distances to get to their workplaces.

Typically, you would expect such projects to be supported by a robust transport infrastructure. Unfortunately in our country, this area has been long neglected.

In fact, if the government seriously wants to house more people, this is the real issue they need to address.

The Delhi Metro is a great example of what well-planned public transportation can do to raise the profile of suburban areas. More of the same is an absolute imperative for businesses like ours.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

How Rao is building low-cost, high-quality homes

Market research can be a waste

My experience in this business so far has only served to reinforce my belief that in some fundamental sense, market research is a waste.

The customer will always surprise you. We have sold about 700 flats till date, but many of them have not been bought by the kind of customer we had envisaged.

We are getting a lot of self-employed people, IT and BPO employees, government personnel, etc, who are a bit above the socio-economic profile we had in mind.

But then this is our first project, we will have to wait and see how things progress when we expand.

Till then, we are clear about our objective. We want to increase the housing stock in the country and in doing so we will keep an open mind.

We are not looking for only tall buyers, or only short buyers or only left-handed buyers! Even if our current customers -- belonging to the sections mentioned above -- do not end up living in these homes, they will rent them out.

We have set up a rental assistance division in the company to help them find tenants, who could be closer to the section we had originally envisioned.

Once the market expands, once we sell a few lakh homes, the broader social benefits of the model will become more apparent.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

How Rao is building low-cost, high-quality homes

Business cannot be skin deep

An important lesson from my career that I have applied to this business is that we need to invest in scale.

We bought more aluminum forms than we needed on day one, and we invested heavily in IT systems right at the outset, so that there would never be a situation when we would fail to cope with increasing demand.

The second lesson pertains to transparency. We are an unknown company in a sensitive B2C business. Why would anyone want to buy a home from us?

To counter any apprehensions -- which so often mar a customer's experience of buying a home -- we have put forth everything openly on our website, right from the carpet area to pricing to the updated construction status.

We have readied a furnished as well as an unfurnished model flat -- furnishing a flat often covers up its real face.

Even though our buyers are not super-rich, we are striving to give them a quality sales and service experience, and people are recognizing this.

On the production side too, with our workers, we are trying to change the template. We are giving them safe, livable shelter.

We don't want to create construction sites where diseased children crawl about in unhygienic, sub-human conditions.

Actually, the additional cost involved with providing these little extra bits is not that much at all, so I am surprised more businesses do not adopt such practices.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

How Rao is building low-cost, high-quality homes

The 'IT' factor

My emphasis on quality standards has a lot to do with my stint in IT.

The best thing about the Indian IT industry is that it is so export-oriented that you are compelled to maintain stringent quality processes.

Foreign customers ask you incisive questions: Are you an equal opportunities employer? What kind of fire-safety provisions do you have? How many people do you have per square feet?

Having faced these rigours earlier in my career, I don't see any reason not to service our domestic, 'not-so-affluent' customers with the same benchmark.

There is yet another lesson I have always carried with myself.

Pei Chia, one of my seniors at Citibank (a former vice chairman of the company) used to tell us all the time, "Whenever you see a customer who is not that rich, remember that he pays your salary."

John Reed, former chairman and CEO at Citi added another layer to this twenty years back. John would tell me, "All this technology means nothing if we cannot use it to provide the same quality of experience to common people as investment banks do to millionaires."

We talk about these values constantly in the company, that just because a customer does not look like Robert Redford, it does not take away from the fact that he is paying your salary by buying your product.

*Jerry Rao is chairman of Value & Budget Housing Corporation. Tanmoy Goswami is managing editor of The Smart Manager.