Photographs: Reuters Rajni Bakshi

The timing of Tata Group chairman Ratan Tata's alleged critique of Mukesh Ambani's opulent home, Antilla, accidentally proved to be ironic.

At just about the same time residents of Golibar, a basti in Mumbai, intensified their struggle against a builder who is demolishing their homes.

Social activist Medha Patkar has been on an indefinite fast since May 21 to focus attention on the demand 'ghar bachao, ghar banao' (save homes, build homes).

On Sunday, Tata issued a statement saying he was mischievously misquoted by The Times, London. It was in The Times that Tata was quoted as expressing concern about Ambani's super-luxury lifestyle while so many Indians remain desperately poor. The British paper has stood by its story.

It is unclear whether Tata did or did not question the wisdom of building a billion-dollar mansion. But that sentiment is commonly and openly voiced by a wide variety of people in private conversations.

. . .

From Ambani's Antilla to Golibar slums

Image: Mukesh Ambani's mansion, Antilla, in Mumbai.Photographs: Reuters

They see Ambani's high-rise luxury home as a form of excess that seems to almost celebrate the unequal distribution of wealth.

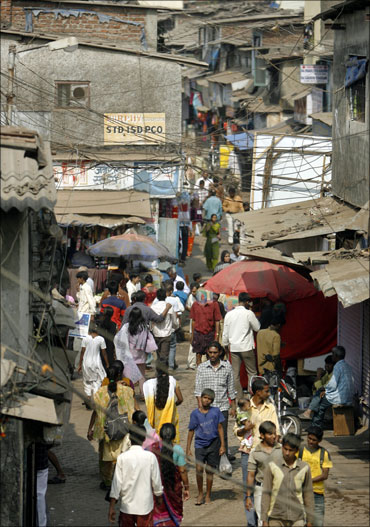

Indeed there is an extraordinarily stark contrast between the mansion in South Mumbai and the reality of Golibar -- with its fragile, tiny one room homes set amid open sewage channels in narrow lanes.

At present Medha Patkar and dozens of Golibar residents are huddled under a tent that provides virtually no relief from the blistering sun. Around them are the remains of semi-demolished homes -- where people are somehow continuing to live.

It is well known that 60 per cent of Mumbaikars live in slums. And yet this contrast of material comforts may not be the most critical divide. The crux of the matter is whether the residents of Golibar can exercise essential democratic rights and be able to make market transactions with the same degree of freedom that economically better off people enjoy.

Why, ask the protestors at Golibar, are we subject to a law that allows the government to award redevelopment projects directly to a builder without acquiring the consent of 70 per cent of the affected people? They are referring to clause 3K of the Maharashtra Slum Areas (SRA) of 1971.

. . .

From Ambani's Antilla to Golibar slums

Image: Social activist Medha Patkar.Photographs: Sanjay Sawant/Rediff.com

The National Alliance of People's Movements (NAPM), which is supporting the Goilbar residents, has written a letter to Maharashtra Chief Minister Prithviraj Chavan in which they allege that the builder, Shivalik Ventures Private Limited, 'obtained the required consent for redevelopment from the State by using fraud. Signatures of housing society residents were forged to show the necessary majority.'

The website of Shivalik denies these charges. Disputes arising out of such allegations have led to various legal actions, which are still pending.

However, the details of specific actions in this particular case should not distract attention from the essential issues that the story of Golibar highlights. The protestors' demand -- that the objectionable clause of the SRA be revoked -- is part of a wider battle for both democratic and economic rights.

In essence, the protestors are asking that redevelopment '. . . take place in a transparent, orderly and humane way'.

The first demand of the hunger strike is that clause 3K of the SRA be revoked. In addition, there is a demand that all projects sanctioned under this clause be investigated and there be no further demolitions till the review is completed.

. . .

From Ambani's Antilla to Golibar slums

Photographs: Reuters

Moreover, the protestors are demanding an overall review of the SRA scheme and modifications that will give them the option to redevelop the neighbourhood on their own.

However, they are also asking for the implementation of the Rajiv Awas Yojana in Mumbai. A statement issued by the protestors says that under this scheme there are no cut-off dates to prove eligibility for rehabilitation. Under the Slum Rehabilitation Act the cut off date for eligibility is January 1, 1995.

This is only the most recent round in a political struggle that has been waged by the city's working classes over decades.

The NAPM is reiterating the familiar argument that slums are not essentially about illegal squatting. Instead, slums are a consequence of the lack of low-cost housing options.

Over the last few years there have been private sector initiatives to facilitate loans and construction of low-cost housing. There have also been some successful slum redevelopment schemes in parts of Mumbai -- where the original residents have got an apartment in exchange for a fragile hutment at the same location.

. . .

From Ambani's Antilla to Golibar slums

Photographs: Reuters

And yet a conflict like Golibar happens because the political economy of the city is such that millions lack the legal entitlements and opportunities that the rich and middle class tend to take for granted.

Concern, even outrage, about a billion-dollar mansion is a reflex that many people are experiencing. But this will not change the future. That will happen only if that outrage is channelled into actions that ensure democratic rights and economic freedoms for all.

Patkar's way of doing this is to help the affected people to organise themselves. Her fast is a way of drawing wider attention and support for these essentials.

You don't have to agree with Patkar's methods or her views on development. There are multiple ways in which we can all work for fairness and equity.

article