Economy after economy has grown on the back of a cheap currency that gave a boost to exports, says T N Ninan.

In March 2012, the rupee was about 51 to the US dollar - not much cheaper than it was a decade earlier.

Through the latter half of 2012, exports continued to fall and soon the deficit on the current account (the sum of all trade, in both goods and services) was more than six per cent of GDP - over twice the danger level, and never reached before.

The rupee came under pressure, reaching 54 by March 2013, then dropping to 57 in June and nearing 60 by mid-July - in part also because signals about a change in the US monetary stance encouraged an outflow of money.

At that point, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) panicked, announcing what sounded like emergency measures that made the markets even more nervous, even as the government had raised tariffs and imposed currency controls as well as import curbs.

Click NEXT to read more...

The rupee tumbled to 69 in a matter of weeks, until fresh signals from Washington and a more confident-sounding RBI governor restored stability. The rupee recovered a lot of ground - climbing to 61 against the dollar before falling back again. It is now below 63.

When the rupee was expensive, India became a high-cost base and exporters could not compete.

As the rupee fell, exports reversed direction. After falling for eight months in a row in 2012, exports see-sawed in the first half of 2013 before a firm growth trend got established.

With the October numbers announced earlier this week, we have seen four months of double-digit export growth. It is hard to not argue that the cheaper rupee (which gives exporters more rupees for every dollar worth of exports) has helped exports to recover.

Strangely, people in authority continue to say that the rupee is undervalued. Some want it to climb back to 58 against the dollar; others pitch it at about 60.

Click NEXT to read more...

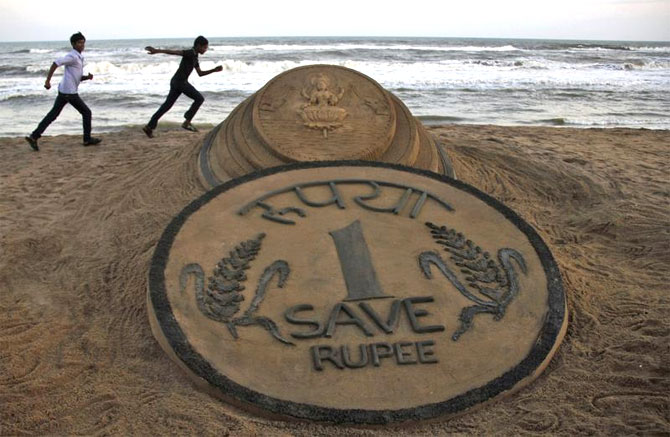

This hankering for a stronger currency at a time when the country still has a large trade gap is hard to understand. Every time the country has had a foreign exchange problem caused by a massive trade deficit, it has been because the rupee was overvalued.

When devaluation followed, sometimes under external compulsion, exports picked up. It happened after the 1966 devaluation, and again after 1991; in both cases, a large trade deficit shrivelled in a few years.

Indeed, there is reason to believe that the trade gap that opened up in the recent past was precisely because the rupee was allowed to climb from about 49 to the dollar a decade ago to 45 and then breach the 40 mark in 2007 before it fell back.

Click NEXT to read more...

Naturally, exporters stopped being able to compete because India became high-cost, and a non-oil trade surplus slowly morphed into a gigantic deficit. Fortunately, the surge in rupee value has been undone, and exports have recovered.

None of this is even remotely esoteric knowledge. Economy after economy has grown on the back of a cheap currency that gave a boost to exports.

Britain suffered a trade deficit with its Indian colony for decades, until it engineered a trade surplus in the mid-19th century by fiddling indirectly with exchange rates (India was kept pegged to silver while Britain switched to gold, which was becoming cheaper after American gold discoveries).

Japan’s amazing post-war success was famously built on a cheap yen. This is elementary knowledge for our policymaking economists who are trained at the best universities in the world.

So why don’t they let the rupee fall if that’s where the markets take it, since there is an obvious pay-off in terms of a better balance on trade? Once exports pick up some more, the rupee will climb again as confidence in India returns.