| « Back to article | Print this article |

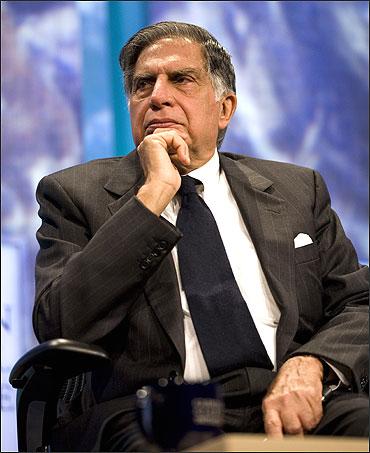

Why an 'insider' will succeed Ratan Tata

So now it appears that the Tata search committee has decided that an "insider" will be Ratan Tata's successor as group chairman when he steps down in December next year (Consensus grows on an internal Tata successor).

And, yes, it's easy to think the result is a foregone conclusion because one "insider" in the running is a member of the promoter family and of "a particular community" as one irate letter writer from Kolkata phrased it.

But even if we set aside suspicions of future nepotism, the search committee could have saved itself a lot of time if it had taken that decision from the start.

Globally, "insider" successors to CEOs are considered the best option for a conglomerate that is stable and growing - which would pretty much apply to most of the Tata group.

Click on NEXT for more...

Why an 'insider' will succeed Ratan Tata

This might be an intuitive finding since it is obvious that the insider understands systems, processes and, most important, the culture and values of the organisation he or she is taking over.

But it is surprising how many corporations opt for "outsiders" and end up with less-than-satisfactory results.

One recent prominent case in point: Hewlett-Packard.

First there was Carly Fiorina, the energetic self-promoter whose zany restructuring plan and ill-judged acquisition of Compaq saw top- and bottom-lines teeter and employees and shareholders head for the exit.

Click on NEXT for more...

Why an 'insider' will succeed Ratan Tata

Her successor, Mark Hurd, a low-profile performer who came from a leading ATM manufacturer, did stabilise the company and won all-round approval.

He may even have flourished there had it not been for one little problem: he breached the company's ethics policy and had to resign.

Click on NEXT for more...

Why an 'insider' will succeed Ratan Tata

On the other hand, companies that have promoted insiders as CEOs have been steadily successful. Pepsi's Indra Nooyi comes to mind in the US.

Indeed, by that yardstick, the outlook is hopeful for Tim Cook, Steve Jobs' successor - just as much as the stint of "outsider" John Sculley, the ex-Pepsi hand hand-picked by Mr Jobs to head Apple in the eighties, ended with less-happy results.

In 2009, Portfolio magazine unkindly ranked him the 14th worst American CEO of all time (Ms Fiorina starred there too).

Click on NEXT for more...

Why an 'insider' will succeed Ratan Tata

Jack Welch's decision to identify a successor in a kind of "open" competition among three internal candidates - Jeff Immelt, James McNerney and Robert Nardelli - well before he retired has become the subject of B-school case studies.

Mr Immelt's performance has more or less validated his decision, demonstrating that star power is not a necessary condition for successful CEO-ship.

Click on NEXT for more...

Why an 'insider' will succeed Ratan Tata

Mr McNerney went on to perform decently as an "outsider" CEO in 3M and now Boeing.

Mr Nardelli, on the other hand, had disastrous stints at Home Depot (earning a Worst American CEO ranking) and Chrysler (the company filed for bankruptcy under him).

Click on NEXT for more...

Why an 'insider' will succeed Ratan Tata

In India, ICICI Bank's chief K V Kamath has been one of the few Indian CEOs to transparently announce the decision to transition to an internal-successor from among a host of candidates.

His successor as MD and CEO Chanda Kochhar has so far proved capable.

In that context, it is worth wondering how Mr Kamath's own "outsider" stint as chairman of Infosys, taking over from its founder N R Narayana Murthy, will pan out.

Click on NEXT for more...

Why an 'insider' will succeed Ratan Tata

Recent research also suggests that the "insider successor" works best in stable or growing companies.

In November 2010, consultants Spencer Stuart conducted a study in the US in which it examined the 300 CEO appointments at S&P 500 companies.

One of its key findings was that in such companies, boards tend to choose internal candidates most of the time.

And, write its consultants, "Those insider appointments, in turn, were three times more likely to achieve outstanding performance than the outsider appointments.

When outsiders were hired into healthy companies, they were twice as likely as insiders to suffer poor performance." (Interestingly, its finding for companies in crisis was exactly the opposite: outsider CEOs did much better jobs than internal candidates.)

Click on NEXT for more...

Why an 'insider' will succeed Ratan Tata

This should not suggest that the internal candidate is always a great thing.

India is something of a special case because much of its big business is family-owned and -managed, so CEO succession is transparently manifest from the time the chief executive starts a family.

This may make for clear management structures, since everyone knows who the boss will be.

But it is scarcely a sustainably healthy way to operate nor does it make for an especially attractive corporate culture.

Click on NEXT for more...

Why an 'insider' will succeed Ratan Tata

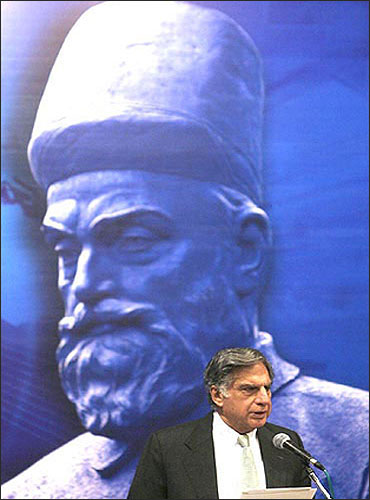

For several decades now, circumstance has forced the Tata family to encourage professionalism over primogeniture within, even if it did not follow that principle for the top job of managing the group.

As a result, it has a large reservoir of youngish managerial talent to tap into.

If it chooses to break with tradition and appoint a "non-family" insider at the very top this time, it could set a healthy precedent for other Indian family conglomerates to follow.