| « Back to article | Print this article |

The rise and fall of Kodak: Why it went bankrupt

Fifteen years ago, Kodak was the fourth most valuable brand in the world after Disney, Coca-Cola and Microsoft.

On January 19, 2012, the company filed for bankruptcy. What went wrong in the interim period?

If pundits and experts are to be believed the reason is very simple. Kodak missed the digital revolution in photography. It did not go digital fast enough.

Click NEXT to read more...

For Rediff Realtime news on Kodak, click here

The rise and fall of Kodak: Why it went bankrupt

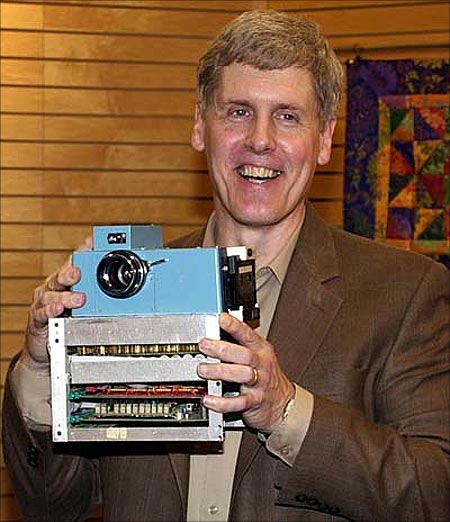

Does the explanation make sense? Yes and No. In 1976, Kodak invented the digital camera.

A decade later it developed the first handheld digital camera. And in 1994, it came out with the first digital camera to be priced under $1000.

Click NEXT to read more...

The rise and fall of Kodak: Why it went bankrupt

In fact, the company even made good money on the patents it held on the digital camera.

As Al Ries, a marketing guru wrote in a recent column after the company filed for bankruptcy, "Kodak holds more than a thousand patents related to digital photography. Kodak recently received, in patent-suit settlements, $550 million from Samsung and more than $400 million from LG Electronics."

Click NEXT to read more...

The rise and fall of Kodak: Why it went bankrupt

That being the case how did Kodak miss the digital revolution? Or did it really miss the digital revolution?

The answer, as is the case with most things in business and economics, is not really as straight forward as the experts would like us to believe.

Click NEXT to read more...

The rise and fall of Kodak: Why it went bankrupt

Big companies like Kodak rarely come up with what Professor Clayton Christensen of Harvard Business School calls disruptive innovations.

These are innovations that transform an existing market or create a new one by introducing simplicity, convenience, accessibility and affordability where before the product or service was complicated, expensive and inaccessible.

Click NEXT to read more...

The rise and fall of Kodak: Why it went bankrupt

A brilliant example in the Indian case is the Nirma detergent. The washing powder targeting the lower end of the market was developed by Karsanbhai Patel, a chemist working for the Gujarat government.

Till then the most detergents in India, led by Surf, used to be very expensive and hence beyond the reach of most ordinary Indians.

Click NEXT to read more...

The rise and fall of Kodak: Why it went bankrupt

Nirma, of course was nowhere as good as Surf, but it was good enough for the Indian housewife who was tired of the "tikiya ragdo baar baar" method of washing clothes.

Hindustan Unilever Ltd (HUL, then known as Hindustan Lever Ltd), the big boy of Indian FMCG, failed to see a market that was waiting to be exploited.

It was left to a rank outsider to come, create a market and then gradually capture it. HUL of course woke up well in time. And to their credit launched their own version of Nirma and called it Wheel.

Click NEXT to read more...

The rise and fall of Kodak: Why it went bankrupt

There are other examples of where incumbents were asleep and it took an outsider to come and create a market.

CNN, when launched in 1980, became the first 24-hour news channel.

Whereas the incumbent BBC, associated with good quality news all over the world, did not wake up to the opportunity.

Click NEXT to read more...

The rise and fall of Kodak: Why it went bankrupt

It took a new player Southwest Airlines to create the low cost airline market in the United States, which gradually spread to the other parts of the world.

The incumbents like Panam, Delta, Singapore Airlines or for that matter British Airways did not spot this opportunity.

Click NEXT to read more...

The rise and fall of Kodak: Why it went bankrupt

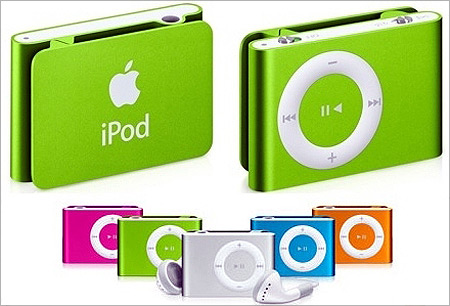

More recently, let's take the success of a product like Apple iPod.

iPod is essentially an extension of the market created by the Sony Walkman and the Discman, which created a market of people listening to music on the move in a very convenient way, without the need of taking big music players around with them.

Given this, the iPod was a product and market that should have been made and captured by Sony and not Apple. But that did not happen.

Click NEXT to read more...

The rise and fall of Kodak: Why it went bankrupt

The case with Kodak is a little different. Unlike the other big boys who were sleeping, it did come up with the innovation that would disrupt the sector it was present in.

But what it failed to do is capture the market that the new disruptive innovation would have created.

The thing is even when big companies come up with disruptive innovations they rarely capture the market that exists for that product.

Click NEXT to read more...

The rise and fall of Kodak: Why it went bankrupt

Mark Johnson explains this phenomenon in his book Seizing the White Space – Business Model Innovation for Growth and Renewal "Just think of Xerox's Palo Alto Research Center, which famously owned the technologies that helped catapult Apple (the graphical user interface, the mouse), Adobe (post script graphical technology) and 3Com (Ethernet technology) to success. Why didn't Xerox exploit them?"

So why is this the case? Over period of time companies grow big essentially because they are good at doing something.

Click NEXT to read more...

The rise and fall of Kodak: Why it went bankrupt

Now any product or technology which is disruptive in nature, calls for them to operate in a different way.

The different way maybe following new processes, requiring new expertise, learning new things or dedicating greater time to the new business.

Sometimes the new business threatens the existing business. And some other times the expected revenue/margins from the new product are nowhere as good enough from the existing product to get the sales guys interested.

Click NEXT to read more...

The rise and fall of Kodak: Why it went bankrupt

And if the sales guys aren't interested, try as you may, the product won't succeed.

Going back to Sony, the market created and captured by iPod was something that Sony should have latched onto. But it could not.

Over the years, Sony along with being an electronics company had also morphed into a music company and had the music rights to almost every big music artist in the world.

Click NEXT to read more...

The rise and fall of Kodak: Why it went bankrupt

Its support for a product like iPod would mean support of MP3 technology which allowed for free copying and distribution of music.

This would mean putting its entire music catalogue out there in the market for free. So obviously the entire proposition did not make sense for Sony.

Click NEXT to read more...

The rise and fall of Kodak: Why it went bankrupt

What about Kodak? As Johnson writes "In 1975, Kodak engineer, Steve Sasson invented the first camera, which captured low-resolution black-and-white images and transferred them to a TV.

Perhaps fatally, he dubbed it "filmless photography" when he demonstrated the device for various leaders at the company."

Sasson was told that his product was "cute" but at the same time he shouldn't be telling anyone about it.

Click NEXT to read more...

The rise and fall of Kodak: Why it went bankrupt

At that point of time Kodak was the biggest producer of photo film in the world. And any promotion of digital/filmless photography would be a direct competition of photo film business.

Hence, the top managers of the firm perhaps rightly decided not to promote digital photography and create a product and a market that will compete with its photo film business.

By the time Kodak realised on the importance of digital photography, others like Cannon had already jumped in.

Click NEXT to read more...

The rise and fall of Kodak: Why it went bankrupt

Marketing guru Ries also feels that the brand Kodak was too strongly associated with the photo film. And that is why it never caught the imagination of digital camera consumer.

Another great example is the personal computer (PC). Before the PC came along the smallest computer going around was called the minicomputer. The leading minicomputer was the Digital Equipment Corporation.

Click NEXT to read more...

The rise and fall of Kodak: Why it went bankrupt

These computers would sell for around $200,000 a piece and generated a gross profit of around $112,500. PCs in turn would generate a profit of $800. Given this the company rightly concentrated on selling minicomputers and not PCs.

As Clayton Christensen, Michael B Horn and Curtis W Johnson write in Disrupting Class - How Disruptive Innovation Will Change the Way the World Learns, "Disruption rarely arrives as an abrupt shift in reality; for a decade, the personal computer did not affect DEC's growth or profits."

Click NEXT to read more...

The rise and fall of Kodak: Why it went bankrupt

By the time DEC realised its mistake, it's time was up. The likes of Apple and IBM had already captured the PC market.

Disruptive innovations have time and again caught the biggest incumbents napping. Kodak is the latest in a series of such companies. And it surely wasn't the last one.