| « Back to article | Print this article |

Singur: A tale of ambition, politics and blatant lies

Unwilling land-losers to the Tata Nano project in Bengal remain the biggest victims of the politics that brought Mamata Banerjee to power in West Bengal, notes Ishita Ayan Dutt

Singur has always been kind to Mamata Banerjee.

First, it resurrected her political career.

Then, just days before the panchayat elections this month, as angst over an unending wait for the return of land acquired for Tata Motors' small car project from farmers who did not wish to sell was growing, the Supreme Court suggested that the company return the land.

Banerjee and Singur share a history that dates back to 2006.

On May 18, that year, a beaming Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee, who had just been sworn in for a second term as chief minister, announced -- flanked by Ratan Tata and Tata Sons' brass at Writers' Buildings -- that the project to make the world's cheapest car, the Nano, would be located in Bengal.

"How do you like the beginning?" he asked reporters, a reference to his attempt to attract big business to Bengal.

Little did he know that this signature project would mark the beginning of the end of the Left Front's 34-year dominance in the state.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Singur: A tale of ambition, politics and blatant lies

It was Bhattacharjee's ambition to put Bengal back at the forefront of industrialisation, and he believed the Nano project was the first step towards realising it.

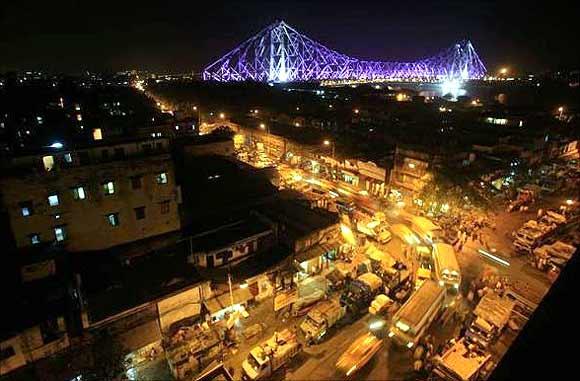

Getting the project to locate itself on agricultural land about an hour's drive from Kolkata wasn't easy.

Tata Motors' interest came with the rider that the state government should offer fiscal incentives equivalent to the value of those offered by Uttarakhand, whose backward state designation allowed it to deliver income tax and excise duty relief.

Naturally, the incentive package an eager state government devised for Tata Motors was extremely friendly.

It offered the following:

(a) Industrial promotion assistance from the state industrial development corporation in the form of a loan at 0.1 per cent interest for amounts equal to the Value Added Tax and Central Sales Tax the Bengal government received on Nano sales in each of the previous years ended March 31. The loan, with interest, was to be repayable in annual instalments after the 30th anniversary of the plant starting sales.

(b) A 90-year lease for 645.67 acres at Singur at an annual rental of Rs 1 crore for the first five years. The rent would increase 25 per cent after every five years for 30 years; Rs 5 crore a year from the 31st year with an increase of 30 per cent every 10 years till the 60th year; Rs 20 crore a year from the 61st year to the 90th year.

(c) A loan of Rs 200 crore (Rs 2 billion) at 1 per cent interest repayable in five equal annual instalments from the 21st year.

(d) Electricity at Rs 3 per kwh. If the rates were raised more than Rs 0.25 per kwh in any block of five years, the government would provide relief through additional compensation to neutralise the increase.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Singur: A tale of ambition, politics and blatant lies

It wasn't this package, which would have meant a significant forfeiture of state revenue, that exercised the politics of West Bengal as much as Banerjee's decision to make the discontent of 2,000-odd unwilling land-losers -- who accounted for roughly 180 acres of land -- the centre of her political campaign.

But from August 24, 2008, Banerjee and her party laid an indefinite siege to the area around the plant.

She claimed unwilling land-losers accounted for 400 acres and not 181 acres as the state claimed.

The 400 acres, she felt, could be retrieved from the vendors' park, which was adjacent to the mother plant, and the remaining 600-odd acres could be reserved for the project.

The demand was untenable to Tata Motors.

To keep the cost of the Nano at Rs 100,000, it was imperative to maintain the integrated nature of the project.

With Banerjee's energetic help, the protests reached such a pitch that Ratan Tata announced the headline-grabbing decision to relocate the project, which it did with even more fanfare to Sanand in Gujarat.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Singur: A tale of ambition, politics and blatant lies

Despite this, Banerjee as chief minister never budged from her position.

Hours after taking charge at Writers' Buildings, the state secretariat, she announced the Cabinet decision to return land to unwilling land-losers.

After a flip-flop over an Ordinance, the Singur Land Rehabilitation and Development Bill was passed in the West Bengal Assembly on June 14, 2011, vesting the entire land allocated to Tata Motors and its vendors with the state government.

A week after the Bill was passed, Tata Motors moved court challenging it.

The first round went to Banerjee.

A Calcutta High Court single-judge order declared the Act valid. The Division Bench (moved by Tata Motors), however, set aside the single-judge order and struck down the Act, primarily because it was in conflict with the Land Acquisition Act of 1894. The state then filed an appeal in the Supreme Court.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Singur: A tale of ambition, politics and blatant lies

It was while hearing an appeal challenging the quashing of the Act that the Supreme Court asked the Tata group to make its stand clear on the leasehold rights over Singur. But it is unlikely that the Tata group will give up the fight.

It's not just about the land; for the group, it's as important to clear its name from the Banerjee government's allegation that it had ‘abandoned’ the project, which is the basis for the Singur Act.

In reality, the plant, at the time of pullout, was 80 per cent ready.

Tata Motors had invested over Rs 1,800 crore (Rs 18 billion) in developing and levelling the land, and constructed the plant in 13 months. Trial production had even started.

". . .no stone was left unturned to ensure that commencement of production happens in time to meet the targeted launch date of November, 2008," the company's petition to the court said.

“Thirteen vendors had also finished constructing their plants, and 17 others were at various stages of construction.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Singur: A tale of ambition, politics and blatant lies

Hypothetically, even if the Supreme Court verdict goes against Tata Motors, returning the land would be well-nigh impossible.

The land belonging to the unwilling farmers doesn't add up to 400 acres, as Banerjee has repeatedly claimed, and more importantly, it's scattered over the 997 acres.

Then again, 11,000 farmers who willingly sold are likely to object if their land were bagged by unwilling farmers, when they had actually given it for an industrial project. Indeed, they, too, are in court challenging the Act.

Still, the court's comments have breathed fresh hope into the ‘unwilling’ farmers of Singur.

They have waited seven years.

They took a leap of faith when Banerjee told them their land would be returned.

But so far, they have neither received the compensation offered from the state government (because they refused to accept the cheques and thereby became unwilling) nor the land.

They remain the biggest victims of Banerjee's populist politics.