| « Back to article | Print this article |

How to prevent future slums

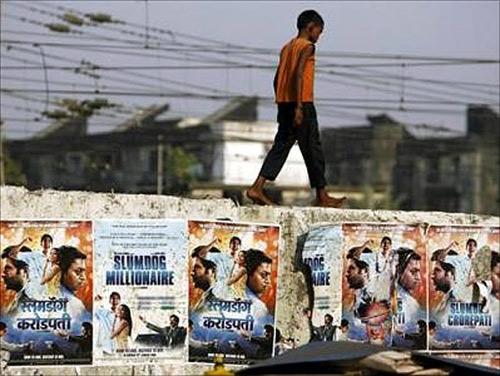

The Slum Rehabilitation Authority in Mumbai is silent on how future slums can be prevented, notes Sreelatha Menon

The biggest challenge in slum upgrade or redevelopment is to establish the ownership of the house built on a plot of encroached land.

And, once houses are handed over, the challenge is to ensure that these remain with slum dwellers and do not get sold off to agents -- paving the way for more encroachments.

Neither government redevelopment policies nor non-governmental organisations are addressing the need for rental housing for the poor.

Many people's groups have taken up the cause of Mumbai's slum dwellers, especially since the city municipal authorities set up the Slum Rehabilitation Authority.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

How to prevent future slums

First, Jockin Arputham and Sheela Patel opposed the handing over of redevelopment projects to private parties to clear land around the airport in supposedly Asia's biggest slum, Dharavi.

Now, nearly six or seven years on, Medha Patkar has taken up the cause of slum dwellers in Mumbai, starting with protests in 2011, and the setting up of the Ghar Bachao Andolan, a parallel to the Narmada Bachao Andolan.

Patkar, who ended her 10-day fast yesterday, was demanding that one particular housing society, out of the 46 societies in the slums in Golibar close to Bandra, called the Ganesh Krupa Society, be allowed to develop according to the wishes of the residents, rather than as part of a redevelopment project in the hands of a builder called Shivalik Ventures, which enjoys the technical support of Unitech.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

How to prevent future slums

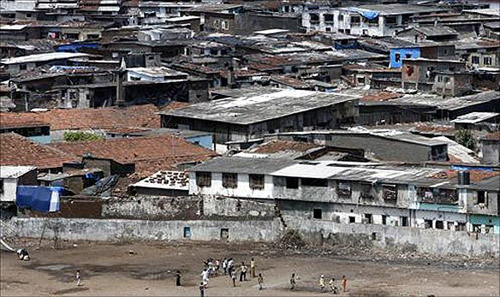

According to the Ghar Bachao Andolan, 45 per cent of the residents in all 46 societies, who are living in the 122 acres of land, are opposed to being rebuilt by Shivalik.

The Maharashtra government's approach to slum redevelopment in the context of Patkar's fast, has so far been criticised by Urban Housing Minister Ajay Maken and activist Aruna Roy, with the latter having sought intervention of National Advisory Council Chairman Sonia Gandhi.

The government has agreed to allow people in Ganesh Krupa to develop their homes in a cooperative model, without the intervention of Shivalik Ventures.

SRA is sitting on 80 different redevelopment proposals from various private builders, whose model is to develop the whole area and hand over housing slots to slum dwellers, while raising a commercial property in the same land.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

How to prevent future slums

Arputham does not agree with Patkar picking on one particular society.

When some process is going on, we must see how best can it be done, he says.

Arputham, who was earlier opposed to redevelopment, has reconciled to it.

But, he says, he wants it to ensure that no one gets excluded for want of documents.

He demands practical steps like mapping and identifying residents by their family photographs rather than asking for documents -- which only a few will have.

Again, he wants a ban on selling of the redeveloped houses and sub-letting.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

How to prevent future slums

Such stringent policies are not possible, since politicians are part of the nexus between builders and agents, he says.

In Kampala, he says, he persuaded authorities to create rental housing for those who were living on rent, and give ownership to those owners who lived in the area.

He feels the policy of Patkar to pick and choose select slums will be a kind of patchwork. It's of no use without a policy change, he says.

Patkar, meanwhile, is waiting for an enquiry report she had sought into SRA, and a written commitment that no houses would be demolished till the report was out.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

How to prevent future slums

She also wants the government to offer the option of Rajiv Awas Yojana to residents rather than thrust redevelopment by private parties on them.

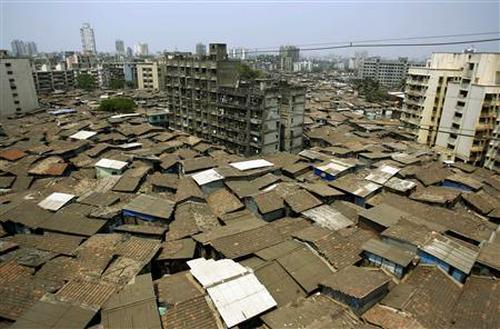

Recently, the Census revealed how slum households comprise 17.4 per cent of urban households in 4,000 towns.

Also, in some cities such as Visakhapatnam, how slums comprise 44 per cent, followed by Jabalpur, Greater Mumbai and Meerut; and how slums are no longer about material want, but inadequacy of cheap housing in a city's plan, leading to land being encroached to fill the gap.