| « Back to article | Print this article |

Can Modi rescue the Indian economy?

Whichever government comes to power after the elections, it will face daunting challenges to revive and sustain economic growth and significantly improve the opportunities for gainful employment, says Shankar Acharya.

Even if Narendra Modi comes to power, the revival of sustainable growth is far from certain.

Last month I had outlined the dismal economic legacy being bequeathed by 10 years of United Progressive Alliance (UPA) rule to whichever government assumes office after the national elections are completed in May (“UPA’s economic legacy: Good, bad or ugly?”, February 26).

To recapitulate, in brief, this grim legacy includes:

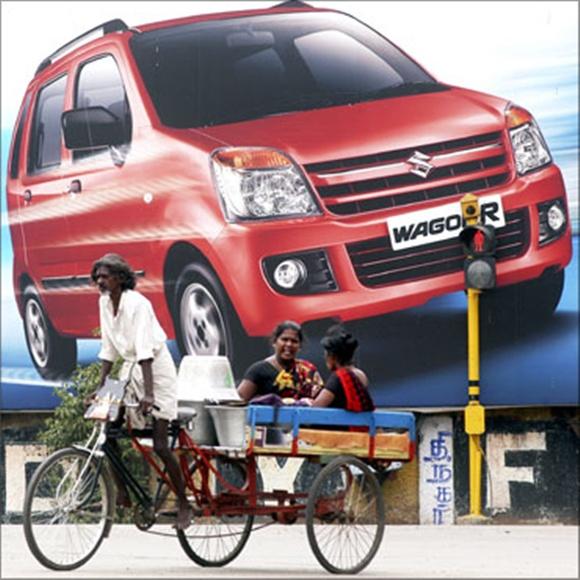

- a mounting scarcity of decent jobs for the 10 million-plus new entrants to the workforce each year;

- an extraordinary collapse in overall growth momentum of the economy;

- high levels of consumer price inflation for the sixth year running;

- an unprecedented stagnation in industrial activity for two successive years;

- continued scarcity of good, efficient infrastructure;

- a growing problem of water stress in agriculture;

- a big overhang of incomplete and underutilised infrastructure projects, casting a massive burden of weak and non-performing loans on the nation’s banking sector;

- a legacy of ill-designed and expensive entitlement programmes and high subsidies, feeding large fiscal deficits and pre-empting resources from more productive public expenditure;

- still weak external sector finances, vulnerable to volatility in capital inflows and foreign trade; and

- a rudderless and demoralised public administrative structure.

Click NEXT to read more...

Can Modi rescue the Indian economy?

Whichever government comes to power after the elections, it will face daunting challenges to revive and sustain economic growth and significantly improve the opportunities for gainful employment.

Clearly, the more coherent and stable the new government, the greater the chance of significant and sustainable economic revival. Many believe that if a Bharatiya Janata

Party-centred coalition, led by Narendra Modi, assumes power in May, then India’s manifold economic ills will be on the way to swift resolution.

Even if this political outcome were to transpire (and Indian elections can be full of surprises), the much-hoped-for economic revival is likely to be gradual and its sustainability dependent on sound policies and supportive circumstances.

Consider the following factors.

First, the assumed political outcome would very likely give an initial boost to confidence and “animal spirits” of both investors and consumers, leading to an uptick of investment and, perhaps, consumption.

Click NEXT to read more...

Can Modi rescue the Indian economy?

However, while a revival of confidence is important, it has to be sustained, and that will be hard to do without tackling effectively the key constraints and weaknesses noted above.

For example, it is an open question as to how quickly the debilitating backlog of stalled and idle projects can be dealt with. This needs clear political leadership, strong inter-ministerial coordination and determined administrative follow-through.

Much will depend on the coherence and politico-administrative strength of the new government, and its ability to re-energise and motivate an administrative structure weakened by years of high-level corruption and bypassing of administrative norms.

Second, even the initial, confidence-inspired boost to investment and consumption may stoke inflationary pressures more than it does growth, if the supply constraints on the latter are not loosened quickly.

Click NEXT to read more...

Can Modi rescue the Indian economy?

One way to reduce this danger is to curb the growth of government expenditure (and the fiscal deficit) to make room for productive investment.

But this will not be easy, given the present government’s well-known postponement into the next fiscal year of massive subsidy dues (for oil, food, fertiliser) owed to the relevant public sector companies and agencies - postponements that are already constraining the operational capacities of these entities.

There are also likely to be large claims on the fisc for recapitalising several public sector banks, highly stressed by their portfolios of non-performing or dodgy loans, especially to stalled or failing infrastructure companies.

And two years down the road, the Seventh Pay Commission’s recommendations may impose huge new obligations for the central and state governments. Nor does the revenue side of the budget offer much buoyancy without a resurgence of economic growth. Certainly, the projections in the present government’s interim Budget for fiscal 2014-15 look fancifully optimistic.

Third, turning to infrastructure, yes, there is some scope for better performance through resolving current bottlenecks like grossly inadequate fuel supply linkages for power plants - even though it won’t be easy to increase production of coal and gas, as the present government has already found.

Click NEXT to read more...

Can Modi rescue the Indian economy?

Looking further ahead, who is going to undertake India’s massive infrastructure requirements in the next few years? The central government will be strapped for cash, unless the new rulers can drastically reduce the bloated bill for subsidies and hold pay increases in check.

That doesn’t look very likely, given the BJP’s track record of legislative support for populist entitlement programmes and other measures such as the recent, new Land Acquisition Act.

The last decade has shown that public-private partnerships are a mixed blessing at best, given their requirements for high governance standards and the unfortunate reality of “crony capitalism”. Besides, nearly all the major private infrastructure companies are saddled with massive debts and low market valuations and are in no position to seriously expand operations.

Fourth, the viability of external finances cannot be taken for granted.

It is true that the large current account deficit of last year has been successfully managed through tariff increases and restrictions on gold imports, some improvement in the underlying trade account because of currency depreciation and the economic slowdown and the expensive swap facilities deployed by the Reserve Bank of India last August. Much of this is temporary or non-repeatable.

Click NEXT to read more...

Can Modi rescue the Indian economy?

The recent pre-election surge in the stock market (and the rise in the rupee value) has been fed by large inflows of foreign portfolio investment. But all this is easily reversible if electoral expectations are belied or the new government’s economic policies disappoint.

And who knows what the evolving crisis in Ukraine will do to oil prices, not to mention other uncertainties in the global arena.

All things considered, the recovery in economic growth is unlikely to be strong, perhaps limited to five to six per cent in the coming fiscal year. And beyond that, it will depend obviously on the functioning of the new government and its actual economic policies. We have to wait and see.

Finally, the massive problem of too few decent jobs for the millions of low-skilled, new entrants to the workforce will continue to grow and bedevil India’s economic and social progress, with real prospects of serious social distress, political turbulence and sharply rising crime.

East Asian economic history shows the way to the only viable solution to the “youth bulge”, namely the sustained growth of low-skill, factory-based manufacturing. So far, India has missed that bus, thanks to its poor education system, weak infrastructure and ill-conceived labour regulations, which severely discourage fresh employment in organised manufacturing.

The prospects for swift and effective improvement in these key policy dimensions are not promising.

The writer is honorary professor at Icrier and former chief economic adviser to the Government of India. These views are personal.