| « Back to article | Print this article |

Why the phenomenal Tata Nano wowed a US university!

"How well will the Nano sell?" wondered Professor Arjun Appadurai at the end of his keynote address at the 'Unpacking the Nano: The Price of the World's Most Affordable Car' symposium recently at the Cornell University, Ithaca, New York.

He had many more questions. "Which markets will it succeed in best? Will the network of distributors, mechanics and suppliers of parts be able to keep up with this market to assure that the car is possible to maintain well?"

"Will the public sector manage roads, signals, and other infrastructure so as to give the Nano the support it needs? Will oil prices allow it to maintain its fuel-effectiveness? Will the Nano be easy to adapt to new fuels and power sources such as electricity? Will the Indian middle classes take to its aesthetics and design? "

He confessed he was no position to offer any expert thoughts on these 'vital' questions.

But he knew that the Nano "is a remarkable bet in the linking of social and technical mobility for India's exploding middle classes."

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Why the phenomenal Tata Nano wowed a US university!

A social-cultural anthropologist focussing on modernity and globalisation, Appadurai -- who has taught at Yale and University of Chicago -- is currently the Goddard Professor of Media, Culture, and Communication at New York University.

He also served as Provost and Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs at The New School in NYC. His several books include Fear of Small Numbers.

While Nano's success as an automobile faces many uncertainties, he said, "its success as a thought experiment in the capacity of the common man to build democratic futures seems already to be a sure bet."

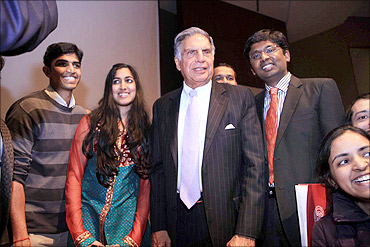

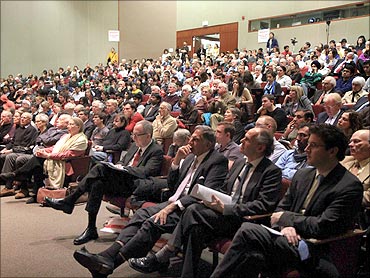

Earlier in his talk, keenly followed by Tata Group chairman Ratan Tata and over 200 students and professors including Cornell University president David J Skorton, Appadurai said that Nano offered new challenges to the Indian middle class.

He said buyers of the cars will be alerted to demand better products from the businesses and also demand better roads and other amenities from the government.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Why the phenomenal Tata Nano wowed a US university!

"I am certain that those who buy, use and ride in the Nano will be induced to think more richly about their own social trajectories in an increasingly globalised world," Appadurai mused. "It will give them no choice but to learn more about design, utility, price, energy, credit and other invisible parts of the infrastructure of modernity. The great visionaries of independent India, including Jawaharlal Nehru and the great J R D Tata, understood that the future is a combination of great technical visions and of great social transformations. They also knew that without the enthusiasm of the masses which seek to learn to navigate the modern world, no design for the future has any legs -- or wheels."

The theme of his talk, 'What Does the Nano Want?' might have intrigued some. He sought to clear the air right at the start.

"In the normal course of things, we ask what customers want, what companies want, what policy-makers want and what countries want and what humanity itself might want," he elaborated. "My title suggests that we might also want to ask what objects themselves want."

The question is not frivolous, he said amidst approving chuckles.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Why the phenomenal Tata Nano wowed a US university!

"In philosophy and the social sciences, as well as in art criticism and other humanistic fields, there has been a great deal of interest in treating objects as alive, moving, living, dying and demanding," he explained. "From at least the time of Spinoza, and coming to the more recent times of Henri Bergson and Gilles Deleuze, various great thinkers have observed that mechanical things are not simply at our beck and call."

"Once imagined, produced, marketed and purchased, all designed things acquire a measure of freedom, autonomy and agency. They appear to develop a will of their own, sometimes making human beings their tools, their friends or their enemies. Who has not seen some of the great comedians fighting with machines, umbrellas, doors or windows? Charlie Chaplin surely knew that all the objects surrounding him could conspire to trip him up.:

"Likewise, Harpo Marx had the talent for making all sorts of objects join him in adding their childish craziness to his own. Laurel and Hardy, later the three Stooges and indeed all slapstick comedians know that every designed object in their vicinity can be a malicious opponent or a friendly collaborator."

In a book he had edited, The Social Life of Things, his fellow authors and he in 1986 sought to show that all objects have social and cultural trajectories, in which they can shift from being gifts to being commodities, from being heirlooms to being junk, from being gourmet items to being garbage, he said.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Why the phenomenal Tata Nano wowed a US university!

"Human beings could begin as free men, be turned into slaves and then rise in politics to become advisors to kings or great charismatic leaders. And Marcel Duchamp showed us that today's urinal can become tomorrow's found object, in the right artistic hands, " he added.

"I believe that the Nano, once it is in widespread use, as it surely will be, will speak for itself, but it will also speak for the approximately 20 percent of the Indian population," he continued, "who can imagine themselves as owning a car, or as owning a car in the near or middle-term."

He discussed several key issues of the Nano phenomenon before answering his question about what the car wants.

The imagination of the aspiring Indian consumer is the main issue with Nano, he declared, not so much its $2,500 a piece price.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Why the phenomenal Tata Nano wowed a US university!

"To such a person, and to his or her family, the Nano is a tool for imagining the future," he said. "First it becomes a tool and a metaphor for the future. It will be a tool in the sense that any first car purchase in a country like India opens its owner to imagining their own mobility in and through the mobility of the car. This is a feature and a potential of all first cars in India. What makes the Nano special, apart from price is its smallness."

Smallness means serious business in India, he added.

"India is not a land which thrives on bigness, in the proverbial American, or Texan manner," he continued.

"It is a society and a culture which thrives on density, intricacy and manoeuvrability. Nor, like Japan, is it a culture which makes a cult out of miniaturization, of smallness for its own sake, of sheer shrinkage or reduction or subtraction as an aesthetic."

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Why the phenomenal Tata Nano wowed a US university!

"Indians are not maximalists, but they are not minimalists either. In India, small is better not because of a hidden Bauhaus sensibility, and less in India is not really more. India is about making as many accommodations to density, intricacy and smallness as a particular scale will allow."

"Indians like the idea of more in less."

In a remark which was received with many understanding nods and good amount of laughter, he said: "Any American who has asked for any private space or time in an Indian household which he or she is visiting, knows the look of puzzlement and slight hurt that crosses his host's face when this suggestion is made. Indians are accustomed to sociality on the rocks, uncut by silences, bodily distance, or private spaces."

"What they demand is that this sociality be well designed, obedient to the needs of ritual, the rhythms of the calendar and the needs and roles of kinsmen and friends. The Nano has the potential to spark the Indian taste for packing more into less, not because all Indians are ascetics, or Bauhasians or green philosophers, but because they like the intricacy and the intensity of sociality."

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Why the phenomenal Tata Nano wowed a US university!

He then talked about an experience most Indians, and many in the Cornell auditorium have either experienced or seen in the movies.

"Take the average second-class sleeper train compartment for the Indian middle-classes," Appadurai said. "What are its features? It is small, it is crowded, it is well-designed, it is cheap and it is taking you somewhere with your companions on your journey, some of whom are family or kinsmen, while others are strangers at the outset."

"Or take any religious procession in any Indian city or village. What are these processions? They are festive self-organising modules of celebration, sociality and density. Or we can strip down this example and think of queues in Indian society, which are ubiquitous. Indian queues are a great lens into the subtlety of non-linear and self-organising social processes, chaotic but not lacking in purpose, norms and outcomes, even while they are irritating, noisy and sometimes fractious."

"Indians know how to get somewhere in the company of others and they appreciate any technology which puts size and price above size and smoothness."

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Why the phenomenal Tata Nano wowed a US university!

While the modern automobile is not like train compartments, processions or long lines, it gives mobility its deep double meaning. "The automobile is the single most powerful tool which stimulates its owner to have a simultaneous experience of social and spatial mobility," he explained.

"I am ashamed to say that anthropologists have not had much to say about how the automobile has transformed India (especially urban India) in the last century. But it is never too late make a start! It is a truism that middle class Indians, by and large, rely on many forms of transport, ranging from buses, trains and taxis to scooters, motorcycles and bicycles, depending on distance and purpose."

"Motorized travel is now the norm for this growing class, and automobile ownership and use is on the increase. Yet, on the whole, private ownership of cars is not a standard feature of the emerging middle class lifestyle, though it is increasingly an aspect of the aspirational horizon."

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Why the phenomenal Tata Nano wowed a US university!

The automobile market across India, which used to be dominated by a few Indian-produced cars (notably the Fiat-based cars of Premier Automobiles Ltd and the workhorse Ambassador of Hindustan Motors), are now fast being replaced by cars produced by Tata, Hyundai, Honda, Mahindra and a few other major Indian companies, and also a growing luxury market dominated by high-end imported cars, he said.

"The meaning of personally owned automobiles in these aspiring middle class households is difficult to summarise in a brief manner, but the Tata Nano promises, and even demands, at least one major change in this market," he added.

Appadurai then said because of its price, the Nano "will be the first car to reflect a part of the journey to upward mobility for millions of households and be a device that stimulates consumption rather than being simply a symbol of social arrival."

"Thus, especially for its first generation of owners and operators, the Nano will be by far the largest, most visible, most modern, most sophisticated designed consumer object relative to its price in the entire bundle of commodities owned by mobile Indians."

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Why the phenomenal Tata Nano wowed a US university!

The small car then is "actually a very large object, when placed in the continuum of refrigerators, TVs and scooters, though small in relation to other cars," he asserted.

"Its social mobility value will be in very high proportion to its rupee value."

Going back to the question what does the Nano want? Appadurai reflected: "Because of its utility, its affordability and its design visibility, the Nano demands of its owner-operator that he or she continue to make further demands both on the private sector and on the public sector. From the private sector, it could be the catalyst that educates its owners to ask for more inventive products (in other areas) that create new packages of price, utility and design that transcend the simple paradigm of conspicuous consumption."

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Why the phenomenal Tata Nano wowed a US university!

"And from the public sector, the Nano could be part of a larger set of social forces that begin to press the state to think more creatively about roads and highways, about environmental conditions, about safety and security on the road, about new forms of financing and credit, and about alternative fuels and energy sources for automobiles."

Nano thus demands a new sort of consumer, he added, "who has a more sophisticated view of the relationship between price, utility, design, mobility, safety and financing. Such consumers are already visible on the Indian landscape, but the Nano has the potential to strengthen their voice."

But more than anything else, the Nano has the possibility for becoming a major consumer product in India that actively stimulates the capacity of Indian consumers to think about the future as something which they themselves can shape through their daily lives, he asserted.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Why the phenomenal Tata Nano wowed a US university!

"In this regard, it could be the automobile which joins a select group of other goods and services -- among them mortgages, medical insurance policies, web-based computing technologies and cellphones which, by their nature, provoke the consumer to think of the future as something shapeable by what they choose to buy, eat, wear, drive, drink or invest in."

"A part of the way in which large economies get mobilized is by the capacity of a growing class of consumers to have the opportunity to buy, own and manage substantial personal purchases."

"The Nano is a bold addition to this category and, as such, it is a tool through which Indian consumers can also grow more acquainted with all the complexities of personal car-ownership and also of the larger social implications of a major shift to automobiles," said Appadurai.