Close to 20 regional stock exchanges, including the big exchanges of Delhi, Chennai, and Bengaluru, have voluntarily exited in the face of SEBI's stringent regulations. Namrata Acharya finds out what makes CSE continue to fight its lone battle.

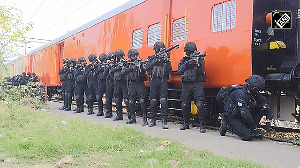

Photograph used for representation only: Mohamed Abd El-Ghany/Reuters.

The interiors of the nearly 79-year-old structure housing the Calcutta Stock Exchange (CSE) hardly give a feel of a defunct institution. While the centrally air-conditioned corridors reek of newly-polished mahogany, chambers of executives are like any swanky new-age office.

Close to a hundred staff still draw regular salary from the CSE.

While all other regional stock exchanges (RSE) have gone for voluntary exit in the face of Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI)'s stringent regulations against RSEs, CSE continues to fight a lone battle, which is pending with the court.

Close to 20 RSEs have gone for a voluntary exit, including some of the bigger ones like the stock exchanges of Delhi, Chennai and Bengaluru.

CSE is betting on two independent studies -- one by Nomura and other by National Institute of Securities Market (NISM), an education initiative of SEBI itself -- to prove its point.

NISM, in its recent study on the viability of CSE, came out with an exhaustive list of pointers for the rationale behind the continuance of CSE. The major being the potential of listing of about 445 companies on CSE that have exited from regional exchanges.

Nomura in its study had suggested potential areas like exchange traded funds, real estate investment trusts, institutional trading platform for equities of small and medium enterprises, formation of clearing corporation and rebranding of CSE.

However, the odds have been against CSE in its struggle for existence.

The tussle started in 2012, when SEBI brought out new norms for RSEs, under which they needed to own a platform, with an annual trading of not less than ₹1,000 crore, to stay afloat.

This apart, the net worth of the exchange should not be less than ₹100 crore, said the norms.

In April 2013, CSE had to suspend trading as it failed to comply with the Securities Contracts (Stock Exchanges and Clearing Corporations) Regulations, 2012.

So long, CSE was executing trade through its in-house clearing mechanism.

Subsequently, CSE initiated talks with ICCL, the clearing corporation of BSE, to meet the clearing corporation criteria.

However, subsequent to signing an agreement in 2014, SEBI issued new norms for Core Settlement Guarantee Fund, Default Waterfall and Stress Test, aimed at enhancing the robustness of the present risk management system of the clearing corporations. SEBI regulations also required that ICCL should be held liable for any risk exposure beyond the core settlement fund, maintained by the clearing corporation of the CSE.

With BSE not agreeing to the clause, the deal fell apart.

In a last-ditch effort to stay afloat, CSE at one point was pitching hard for an alliance with all RSEs in the country. The idea, also mooted to SEBI by CSE, was to project the Kolkata-based exchange as the only national exchange. It had already forged in-principle tie-ups with four RSEs -- the Madhya Pradesh Stock Exchange, Over-The-Counter Exchange of India (OTCEI), Ludhiana Stock Exchange, and Bangalore Stock Exchange.

CSE had a trading turnover of ₹9,228 crore during 2012-13, and around 2,200 firms are exclusively listed on the exchange with about 700 registered trading members.

As of March 31, 2016, the exchange had a net worth of ₹103.2 crore.

It is also betting on its real estate pool, currently valued at ₹300 crore to start its own clearing corporation, said a source at the exchange.

Notably, BSE has a 5 per cent stake in CSE.

© 2025

© 2025